When I’d just gotten Feng Na’s poems published in this last edition of Drunken Boat, Trump had won, which meant something very new for a group of people among which I count myself — diasporic or overseas Chinese, people who’d decided, after being told for twenty years that there was a string hitched to our feet, to see where that string ran from. I’d been coming back to China for summers since I was little. I saw it as the place I’d get a bit of oomph to triumph over the bland, white culture I’d grown up in, so powerful that it could make itself unseen, claim to be not white culture, but culture par excellence. Which is why the first attempts at fiction I wrote suffered, I think, from imposter syndrome. Hard not to want to feign Protestantism, immerse myself in suburban drives and waffle houses, when people like me in the books were bucktoothed and shifty-eyed, or, if the books were contemporary, brainy but inarticulate. I got over that, of course, but China remained a place from which I got stories — exotic currency — which my friends who pretended to cosmopolitanism had never seen. It never occurred to me that the opposite would happen, that one day, I would be explaining to my Chinese classmates what gerrymandering was, why so many people — white people, no less — were suddenly afraid. These were the liberals, I told them. They are thunderstruck at having been called to a fight they never believed was real. To them racial difference is like a cereal ad or a poster. I came up with an easier image. Imagine glass. Imagine all the birds who kill themselves smacking themselves on what they don’t see, what they think is air. Now imagine a bird — poor bird, huh — that flies so fast, so tremendously fast, into the glass that its body cracks that surface. You’ve seen a pane of glass crack? The cracks radiate out, like a spiderweb, from the point of impact. Now take this bird, and imagine he is a dead black boy. Now no one, not even the millionaires who made the glass, can pretend it’s not there. And the other people, the ones who bought the glass just so they could make houses out of it and pretend it wasn’t there when all the poor black and yellow boys try to get in, now they can’t pretend anymore either.

That’s sort of what’s going on in America now, except it’s always been going on, and I’m just now old enough to see.

White precarity had become the subject of the day. And now I want to shift, for a bit, to Noam Chomsky’s speech on the climate summit in Marrakech. Chomsky said something in the spirit of this change I’ve just spoken of. He said the climate summit was a “quite astounding spectacle”, because, now that Trump would begin rolling back the changes in environmental policy that Obama had made, “The hope of the world for saving us from this impending disaster was China — authoritarian, harsh China.” This kind of inversion of expectations is called chiasmus: ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country; it was not that I loved Caesar the less, but that I loved Rome the more; it’s when the going gets tough that the tough get going. And of course, that is what people like us, the hyphens — British- and Canadian- and Australian- Chinese, or the other way, depending on how we are feeling and to whom we are catering, are very familiar with.

And so chiasmus performs one’s duty to be humble, while absolving one of the hard work of learning, not how the other is “superior”, but how the other is different. And by difference I do not mean otherness, I mean a complex set of lived experiences which can seem as mundane as what time of day someone drinks tea, but which, taken in total, comprise entire galaxies of meaning.

Authoritarian, harsh China. Though Chomsky is certainly not someone who lacks information about China, the rhetorical inversion, which Eve Sedgewick calls chiasmus, is something that well-meaning liberals trip over themselves to make. Things subject to chiasmic valorization: poorer countries’ academic achievements, the kindness of blue-collar people, black and brown excellence. It tends to be a bit disappointing, however, to those of us interested in “area studies” because it’s a move an American can make, conceivably, with any culture they are unfamiliar with. Of course they’re better than us, goes the formula, I’m not surprised at all. As Sedgewick cannily points out, chiasmus works by masking a crisscrossing and uneven set of power relations with a symmetry. Her example: a man’s home is his castle. “The man who has this home is a different person from the lord who has a castle; and the forms of property implied in the two possessives are not only different but…mutually contradictory”.

And so chiasmus performs one’s duty to be humble, while absolving one of the hard work of learning, not how the other is “superior”, but how the other is different. And by difference I do not mean otherness, I mean a complex set of lived experiences which can seem as mundane as what time of day someone drinks tea, but which, taken in total, comprise entire galaxies of meaning. One example: here, in Beijing, I am often honked at by cars that overtake me, even if I have been driving, steadily and smoothly, on the side of the road. Every time it happens, my small-town, polite-to-a-fault instincts kick in, and I must try very hard not to think nasty thoughts about the person behind the wheel. Yet what is important here is to understand that I have confused a signal — honking, here, is a courtesy-move, like calling, on your left, and is necessary, since traffic tends to be much more densely packed — for the noise. Pile enough of these misinterpretations together and you get a disastrous result: an expat who, for all intents and purposes, “knows” an awful lot about what a loud and rude place Beijing is — no, what a loud, rude soul the Chinese person has. This is the ugly side of a chiasmic inversion, a chiasmic inversion that has died on the lips of a person whose goodwill has run out and who has never really had to learn about the recipient of that goodwill.

I met Feng in one of my classes last year where she was a visiting speaker. My classmates were Slavic, Eastern European, Latin American, two boys from the States. Feng was a friend of my professor’s — they’d met at Capital Normal University, where my professor had completed her PhD, and where she visited when Feng happened to be the poet in residence. In our seminar, which had been offered to all international students, most people quietly listened to Feng speak about her admiration for Karen Blixen, how Faulkner’s little quote about how the provincial can be universalized helped her, as someone who was from rural Yunnan, and so on. My classmates kept quiet out of shyness, and I out of a sense of not wanting to be combative or showoffy — something I always do when impressed, or threatened. The politest student in our class asked Feng what sort of audience she wrote for. Feng said she didn’t want to think about that — she could never know what sorts of people read her poems. Of course, she did think about it, all the time, but only with a kind of wry resignation. Consult “Whom Are Poems Written For”, for a fanciful take on this. Poems, the speaker tell us, are for:

Early risen travelers, sweepers of snow,

mothers departing sickbed-ridden lives,

mountaineers who find wisdom in the wingbeats of a moth.

The tramp leaning on a tree thinks suddenly of a guitar twanging at home.

To fell a tree in winter, someone else must pull the rope,

a singular work

to make the wood into boats, into vessels

for food, well water, crematory ash,

using the profits to bribe a callous hitman

who, however, finds himself in a hesitation like love.

A reader of poetry mistakes the poet’s meaning.

Each gropes for the world’s switch amid her own darkness.

Feng, I was going to discover, was a poet who hated, not confessionalism, but an attempt to sensationalize the self — one such poetic movement, quite big in recent years, is called the “Below the Pants School”. One of its leading lights commonly publishes things like this:

Once

she was stopped by a couple of hoods

one of them squeezed my sister’s ass

said: not bad, feels like a persimmon

“Poems like these don’t belong in the category of poetry,” she told me. They were cheap thrills. Feng, by contrast, is a quiet, understated observer. Of the poems in her new collection, many are about transit, migration, yearning, the great fight for recognition and the pain of its being denied us. Her most painfully confessional poem is called “On My Thirtieth Birthday, an Earthquake”, and in it the speaker uses most of her lines to talk about her mother’s fragile, beloved body sleeping beside her, and then, in the final line, says, “Mother’s greatest fear is that there is not a younger man to love me.” It’s like a piece of ice dropped down one’s back, and connects, as often with Feng, the natural with the historical — hers is one of the first generation of women who are not getting married in their twenties, and on whom there has been enormous pressure. Or in another poem, “Searching for Cranes”, the poet imagines going into the wilderness of Bayinbukele, Mongolia and having a failed tryst with a rearer of cranes: “She has a hundred and eight ways of hiding/ the rearer of cranes needs only one to find her:/ in Bayinbukele/ all the cranes he’s touched must come home to roost”. The one hundred and eight ways is a reference to The Water Margin, that crypto-anarcho epic whose one hundred and eight heroes are fighting an authoritarian law. Yet the romance here is Madame Bovary’s kind; the speaker — this is all in her head, anyway — wants to lose to this authority, wants to be brought back into its orbit.

When Feng finished answering my classmate, she looked around, waiting to see if we had anything more to ask. When no one spoke, she said that she supposed we weren’t too familiar with Chinese poetry.

Hold on, I said.

I’m afraid what I said next was huffy — it always happens like this. I told her that I did know about Chinese poetry. I spoke about the bad book of poems I’d self-published in high school, about discovering John Ashbery, and Ben Lerner, realizing that I could not beat them, ever, and quitting. Feng, perhaps sensing a challenge, told me that if I’d only done it in high school, there was no way I could say I didn’t care much for writing poetry. Who could tell, if I kept writing, what sort of things I’d produce? No, I told her. I was done writing poetry, I said after a moment, because I thought I was better suited to essays and translations. The rest of the conversation was more measured, and by the end of the lecture, I’d given her my information. In our correspondence since then, I’ve explained to her that poetry, of the kind I envied as a high schooler, was exactly the same as the fiction I wrote: it seemed like an imposture, and I always found myself wanting to break off and talk about an imaginary China. Now I was here, I supposed. We shifted, of course, to publishing (Feng isn’t a minority, and my mistaking her appearance for that of one came from committing an error I resent in other people), something she feels anxiety about always. In China, she said, most young poets, even good ones, had to self-publish. There are fellowships and grants and awards, of course, and with those come book deals, but she and several others she knew had gotten started using money from their own pockets to put out books. And speaking to books, she was surprised that in the states, people read pamphlets — chapbooks, I corrected — when she was only guaranteed publication of a book of poems if it was over 100 or so pages. For my part, I told her about my anticipation of that day when print books cease to be anything other than oddities, about the promise of online journals, and a couple of other crackpot millenarian hopes.

And so it’s to be expected that Stephen Owen, an eminence of Chinese Classical Poetry at Harvard, would say in an interview that all contemporary Chinese poetry was inferior, because as long as it was trying to abide by Western forms, it would never catch up; he forgets to add that as long as he lives, he and his will make it difficult for Chinese scholars to catch up to conservative East Asian Studies departments in the West.

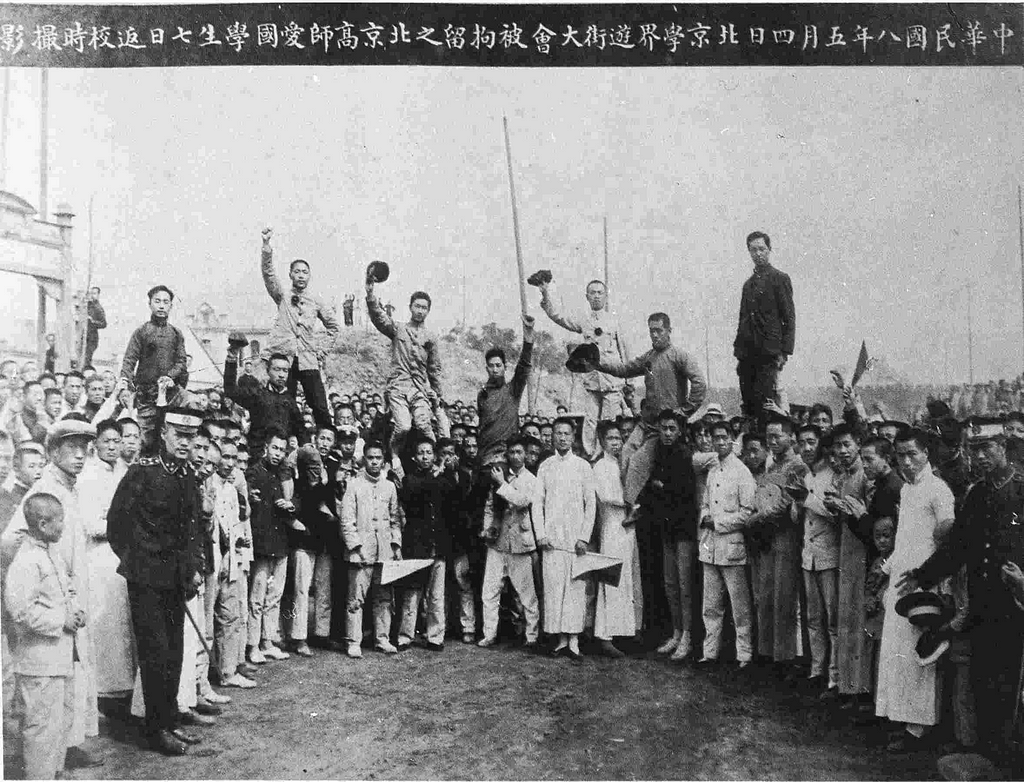

In her first email, she’d attached her bio. Born in 1985 in Lijiang, Yunnan. She graduated from Sun Yatsen University, in Guangdong. She is a member of the Chinese Writer’s Association, and is a commissioned writer for the Guangdong Literary Guild. Books include Searching for Cranes, A Season in Tibet, and Orchard of Numberless Lights. Winner of the Huawen Young Poet’s award, the Benteng Poetry Award. She’d made a valiant effort to translate the whole thing into English. Here is a part of the asymmetry I am trying to write about: Feng, through subsequent emails, told me that she considers it a great shame how few mainland Chinese poets speak fluent English. China is still, on the whole, a monolingual country. When Bei dao was in his early teens, learning a foreign language was the least of his worries — his high school closed down because of the Cultural Revolution. Indeed, his whole generation of poets did not go to school or, if they were lucky, when the Gaokao was reinstated in 1977, were able to go in their mid-to-late twenties. One of my favorite poets, Ouyang Jianghe, frequently tells his students that despite all the honorary degrees conferred to him, his lack of a real degree means that all of us are luckier than he was. Nevertheless, it is almost certain that for the small group of people who were able to access foreign books during the 60s and 70s, their welding-together of that period of Chinese life with the eclectic material they got their hands on created what has been known as the second boom of modern Chinese literature — the first being the May 4th movement, almost sixty years ago. You can read about that movement, which has been credited as the first where Ethnonationalism, Modernism, Communism, and many more isms were talked about, elsewhere. After Deng’s reforms, literature in the 80s began, in Bei dao’s terms, to erupt with a huge stream of voices which could only be underground before — words like Modernist and Avant Garde began seeing currency. Novelists like Ge Fei and Can Xue and Yu Hua began writing stories influenced by Freud, Kafka, and Borges.

Feng felt ambivalent about this — she appreciated that it was translated texts which had brought something from the outside, but she had a word, fanyiti, which means “translationese”, for writing that has become indistinguishable from translations of foreign text. And of course, Chinese poems that sound awfully like fanyiti are often welcomed by, because they are legible to, Western readers. Partha Chatterjee, in his brilliant polemic, “Whose Imagined Community?”, explains the dilemma like this. “Bengali drama had two models available to it: one, the modern European drama as it had developed since Shakespeare and Moliere, and two, the virtually forgotten corpus of Sanskrit drama, now restored to a reputation of classical excellence because of the praises showered on it by Orientalist scholars from Europe…their aesthetic conventions fail to meet the standards set by the modular literary forms adopted from Europe… Having created a modern prose language in the fashion of the approved modular forms, the literati, in their search for artistic truthfulness, apparently found it necessary to escape as often as possible the rigidities of that prose.” We would have to modify this significantly with China, of course, supplementing “nationalist” art with “dissident” art, but the basic statement of where the power lies rings true. Can Xue, for example, is an author beloved in the United States, but she is relatively unknown by the literate middle classes in China. On the other end, a Chinese poet like Haizi, the most famous Chinese poet in China, has suffered international neglect because, I suspect, he’s neither a dissident nor a fancy formal innovator. As for the classical route, very few Chinese poets go it because it’s considered pat — same as regularly rhymed stanzas. And so it’s to be expected that Stephen Owen, an eminence of Chinese Classical Poetry at Harvard, would say in an interview that all contemporary Chinese poetry was inferior, because as long as it was trying to abide by Western forms, it would never catch up; he forgets to add that as long as he lives, he and his will make it difficult for Chinese scholars to catch up to conservative East Asian Studies departments in the West. Yet it still surprises me and hurts me.

Feng doesn’t like readings that are too political. The speaker in “Birthplace”, for example, says:

People always bring up my birthplace,

a cold Yunannese place with camellias and pines.

It taught me Tibetan, and I forgot.

It taught me a tenor; I have not yet sung

in that register, hidden somewhere, hard as pine nuts.

there are Muntjac in the summer

and fire pits in winter

the locals hunt, harvest honey, plant buckwheat

because it’s hardy. Pyres are familiar to me:

we don’t pry in Death’s private affairs

or those of comets striking ruts in the earth

They taught me certain arts

so that I might never use them

I left them

so they would not leave me first

they said that people should love like fire

so that ashes need not burst back to life

It is a beautiful and elegiac poem about losing one’s ethnicness, about passing, in other words, for Han Chinese. Strange for someone like me, who associates Chineseness with nothing but ethnicity, to read a poem that stages the dominant ethnicity as Han, and therefore, as transparent. Feng is a member of the Bai ethnicity. She grew up in a small village in Yunnan, close to the border with Tibet. Feng is no “tribal” poet. Even in poems where the poet is unabashedly ethnic, like “Drinking with the Yi”: “They say, let the leopard out of your chest/I smile: drinking wine is like stringing a bow/…We use Han words to play a finger-guessing game, blood running into the cups…” her presence is still that of an observer not quite at ease. In her childhood, she spoke a dialect of Tibetan, which she has altogether forgotten since. A tenor is “not yet sung,” arts are “never used.” Yet despite our differences — Feng, I think it fair to say, has passed for Han Chinese, whereas I will never pass for white — the negation in her poem connects brilliantly with the idea of race as something which, by disavowing, one reveals as always already having existed.

In China, where the first generation of women professionals is being met with no small amount of male recalcitrance, [Na] is a bit of a standout: a woman poet who has won numerous awards and yet is told, time and again, that her poetry is too sweet, too lyrical, though it probably comes from her gender.

We argued about this point. One gets pulled into one’s identity, I argued, and the only thing one could do is play within those strictures and complicate them. Feng, on the other hand, wanted to be read, not as a Chinese poet, not as a woman, but as a person, a human. “But not everyone qualifies as a human!” I wrote back. “No,” she responded. “I agree. Not everyone qualifies as human.” And listed ways that she believed the feminine and the Chinese come through in her work — I had to calm down. If it was not identity politics she was doing, neither was it respectability politics. I was putting too much of myself into this argument. I had misunderstood a sign. I thought of car horns honking, and then I thought of Feng — who, of course, is a woman and Chinese and ethnically Bai but who has had to endure essays that use gender or ethnicity or nationality to sanitize a detail. I had only to wait to see exactly how bad it could be: Feng’s book, Orchard of Numberless Lights, came out. I was invited to the conference and book signing. I had never been to an academic conference in China before, and despite its relative casualness (the writer being discussed was present, after all, so the critics were not particularly harsh), I was sweating when I spoke. I defended a few of my choices as Feng’s translator (using “guitar” instead of “guqin” — a violent move, I had to admit, but one which the poet had consented too — and “moth” instead of “butterfly — an issue of which tropes have become tired in English, and not a very big change), and then fell into silence. I listened to the critics, who all seemed to follow the same formula: praise and then critique. One critic’s words stand out: he said that while Feng’s poems were all quite beautiful, sometimes the they were“too flawless, sometimes to the point of being cloying.” Perhaps, he added, it had something to do with her gender. Na smiled at him and made notes on a sheet of paper. She said she was grateful for the advice and would keep it in mind. Her ability to keep cool surprised me — for my own part, my jaw dropped. Later, when I prompted her, she said that a male poet never would have received such criticism. In China, where the first generation of women professionals is being met with no small amount of male recalcitrance, she is a bit of a standout: a woman poet who has won numerous awards. Threatened? I wanted to ask the critic.

Bei Dao has expressed the desire to go back and teach at his high school, where he was when the Cultural Revolution broke out — of his own free will, and not because of some set of “socialist values.” Why is not for me to say — I can’t understand what, for someone else, makes home home.

The most famous Chinese poet, Bei Dao, finds himself in a similar dilemma. He’d gotten famous in the 80s for being a dissident. Pen America’s bio of him says that “In 1989, Bei Dao was accused of helping to incite the events in Tiananmen Square and was forced into exile from China. Since then, he has lived in seven countries, including Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and the U.S. Since 2007, he has been a professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.” Yet PEN America, and many other foundations and websites concerned with freedom, human rights, ignores Bei dao’s own resistance to such a tag. And by the way, to progressive critics who don’t know very much about Tienanmen, it might be fruitful to follow up on its leaders’ whereabouts. Many ended up on Wall Street. Rather than call Bei Dao a “reactionary”, one might see him as someone who has noted the way that “freedom” gets subsumed by neoliberal humanitarianism, one which fundamentally denies certain people rights because they don’t qualify as human. One can imagine the dilemma Bei Dao faces — accept speaking invitations in the States where he will be bombarded about why he is no longer protesting the CCP, and where no one, absolutely no one, will talk about his poetry in terms of its beauty — or make peace, yes peace, with the country in which he was born — a country of people, mind you, and not merely a “regime”. Bei Dao seems to have opted for the latter. He has expressed the desire to go back and teach at his high school, where he was when the Cultural Revolution broke out. As for what exactly made him choose, that’s not for me to say — I can’t understand what, for someone else, makes home home.

This is difference, par excellence — not some exoticized, othered thing — but something which, no matter how it may threaten us, is someone’s home, their daily life. It is, in other words, transparent to them even if it is not to us. And as to exactly what the content of that “it” is, exactly, I cannot say. I still hear that honking, in my end-of-day commute, when I am tired and life seems like something on the other side of a keyhole, and I have to admit, these are the times it is hardest not to hear that noise as something threatening. I think my home raised me to think this way.

Perhaps it’s good end at one of Feng’s own poems, “Rifle”:

I’ve memorized the order: open the breech, load powder and bullets,

close the breech. […]

The metallic cold gives off a living stench.

Since growing up I’ve often smelled it in crowds.

I know the trigger pull and the instant of fire.

I’m glad to live in a country where guns are not for sale.

On the face of it, “Rifle” is a poem about first- and second-order hate, the deed and the deed deferred through writing. It is with the sixth line, “Since growing up I’ve often smelled it in crowds,” that we understand the smell of sulfur is similar to the simmering anger that people feel, that the poet feels. The final line is tantamount to the poet’s saying, “If not for this obstacle, well, you know what I’d do to those people, you know which people I’m talking about.” The obstacle doesn’t matter, if we are going to be psychoanalytic: were the poet not in China, she would find some other excuse not to do what part of her knows, already, is forbidden. Yet most readers living in the U.S. and versed in poetics will not be reading the poem like this. I’d wager most of them will read it in two ways: the first being disgust at another “regime apologist” Chinese poet, the second being the leftist move of saying, flippantly, “Of course it’s harsh, authoritarian China where the world finds an example of restraint.” One almost wants to add, “Told you so,” afterwards. The impulse then is to say the poem has been decentered by an overly politicized reading; yet doesn’t the poem itself, embedded with this incidental and highly historical detail, become like a piece of amber, embedded with a shard of bone? This would make the poem different both from apologetics and from dissent, different from an apolitical poem and different than an intentionally political one. It would be, instead, about the perniciousness of the hyphens we and our imagined doubles, reading halfway across the world, always find ourselves resorting to in order to explain ourselves.

Feng Na, Chinese Poetics and Chiasmus was originally published in DrunkenBoat on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.