During the years I was hiding my obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) symptoms, and especially as I quietly began to write about my symptoms, I’d longed for connection not just with other people with lived experience, but with other writers who were thinking about the same question: how can OCD fit into the shape of a poem?

I’d long clung to a couple glimmers of recognition that had broken through the fog of my isolation: a 2013 video of Neil Hilborn performing his poem “OCD,” Paige Lewis’s 2018 essay “Portrait of the Poet With OCD & Pogo Stick.” Then, in 2023, a flurry: a four-poet folio on OCD poetics curated by Raye Hendrix, who was also at work on her doctoral dissertation on invisible disability in poetry, including OCD. The fact that there was someone out there studying something she called “OCD poetics” — that there were enough poets writing about OCD for an OCD poetics to be conceived of at all — made me feel as if I wasn’t floating in a vast ocean alone but in fact, a net was weaving itself just under the surface, which at any point could be dragged to shore, and we would find each other there, bundled together. I felt that connective tissue threading across cyberspace, tying knots across the page from writer to reader, poet to poet.

At the time, I was gearing up for a flurry of my own: the early 2024 publication of Exploding Head, my OCD memoir in prose poems. I was pitching events, recording podcast interviews, nervously sharing my diagnosis more publicly than ever before. And then poet Dan O’Brien published his essay on the sustaining practice of writing through lived experience of OCD in The Washington Post, which concludes with the sentiment, “I feel at once helpful and hopeful.”

That was it, exactly! I also felt at once, having written my own poems, helpful and, sensing an increasing number of OCD stories being told through poetry, hopeful. I was truly not alone. My book would be published in the U.S. in February, and six months later, in August, the Canadian poet Samantha Jones would publish her own full-length collection on living with OCD, Attic Rain. Two poetry collections on OCD hitting the shelves in one year: what were the odds? I could not wait to see how Jones had fit OCD into the shape of a poem; and would it be anything like the shape of mine?

So in late 2024, when I would finally get a copy of Attic Rain in my hands, my reading would be colored not just by my year-long eagerness of the book’s publication and by my own lived experience with OCD, but also by the more-than six months I’d spent on the road promoting my own book, interacting with readers. And being, at times, misunderstood.

OCD has a way of isolating us, even within our own community. Recently, a writer with her own OCD diagnosis told me she’d gone “looking for the OCD” in the pages of my book. But what she’d found instead was mostly imagery. Of course, I thought, because imagery is primarily how I experience OCD. She had read Exploding Head, with its obsessive, intrusive imagery of accidents and bullets and knives and drownings and angels with their terrifying rules and secrets — literally my lived experience of OCD on every page — and still she had asked me: “where is the OCD?”

But I get it. She had come to my book looking for her own lived experience with OCD and didn’t find it reflected there. She had come looking for a diagnostic label and didn’t find it named there. When I wrote the poems that would become Exploding Head, I had thought that my experience of OCD was so obviously OCD that I wouldn’t need to name it at all. This was before several early readers encountered my ultra-realistic, hallucinatory-like visions and guessed schizophrenia. It was before comments on social media revealed that some readers didn’t know OCD can be invisible — that mental compulsions can consume hours of your day and can be just as disruptive as those more commonly known — and visibly evident — symptoms such as compulsive handwashing or checking locks.

It was important for me, as a poet, to create an immersive experience for my reader, a world on the page that was most like the world inside my brain where the certainty of reality and the constant doubt of OCD are conflated, even if it meant that sometimes that experience felt bewildering. After all, that’s how I had felt as a child experiencing OCD symptoms before I knew there was a thing called “OCD.” The frightful intrusive thoughts are just as frightful today, even though I now know the diagnostic term that can explain them all away.

The reality is, OCD is both one of the most well-known and most misunderstood diagnoses. And it had become clear that my flavor of OCD was apparently not one that popular culture had often tasted. Finally, so there wasn’t any confusion about the diagnosis of the speaker in my poems (i.e., my diagnosis), I decided to label “OCD” on the back cover copy of my book.

But with Attic Rain, the diagnostic label of OCD is more than a note on the back cover copy. Samantha Jones positions herself — and her diagnosis — center stage in a direct address to the reader. Set in the front matter, prior to the Table of Contents, a paragraph begins:

Dear Reader,

Thank you for choosing to spend time with Attic Rain. This collection contains autobiographical works that explore obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) based on my lived experience. …

“Each person living with OCD,” Jones continues, “will have their own unique experiences, and I cannot speak on behalf of the entire community.” Signed: “Sincerely, Sam.”

After having spent nearly a year anticipating this book’s publication (two full-length collections about OCD hitting shelves in 2024? What were the odds?), and knowing everything I know about OCD, part of me was disappointed to see this prefatory note. I had been eager, greedy even, to be thrust directly into the author’s lived experience, such that on first read, this explanatory directive felt like a barrier against the poems I was more than ready to get on with reading. Perhaps, as my reader had looked for her own experience of OCD in the pages of Exploding Head, I had been looking for my own poetic choices in the pages of Attic Rain. And I did not find them there.

But you know what? In retrospect, I’m impressed. How intelligent this poet is in having thought through how her book might be received, in anticipating what readers might be looking for when they search these pages, and in letting them know upfront: hey, you’ll see OCD here, but you might not see yourself. Jones is having, essentially, the exact conversation I had with my reader, but Jones is having the conversation before her reader reads her book. She is setting the tone, establishing a pact of clarity. Maybe it isn’t necessary. But perhaps it is wise.

Samantha Jones’ experience with OCD is largely centered on checking and safety. I don’t check locks or the stove or perform other repeated actions before leaving the house; in fact, I very well may burn down my house one day. But that hardly matters. I didn’t come to this collection looking for my own lived experience with OCD to be reflected there, and even if I had, Jones would have set me straight before I hit the TOC.

What I did find in the pages of Attic Rain is a uniquely harrowing, musical, and formally varied exploration of OCD, an anxious wrestling against uncertainty and doubt, and an authorial presence that balances both vulnerability and craft.

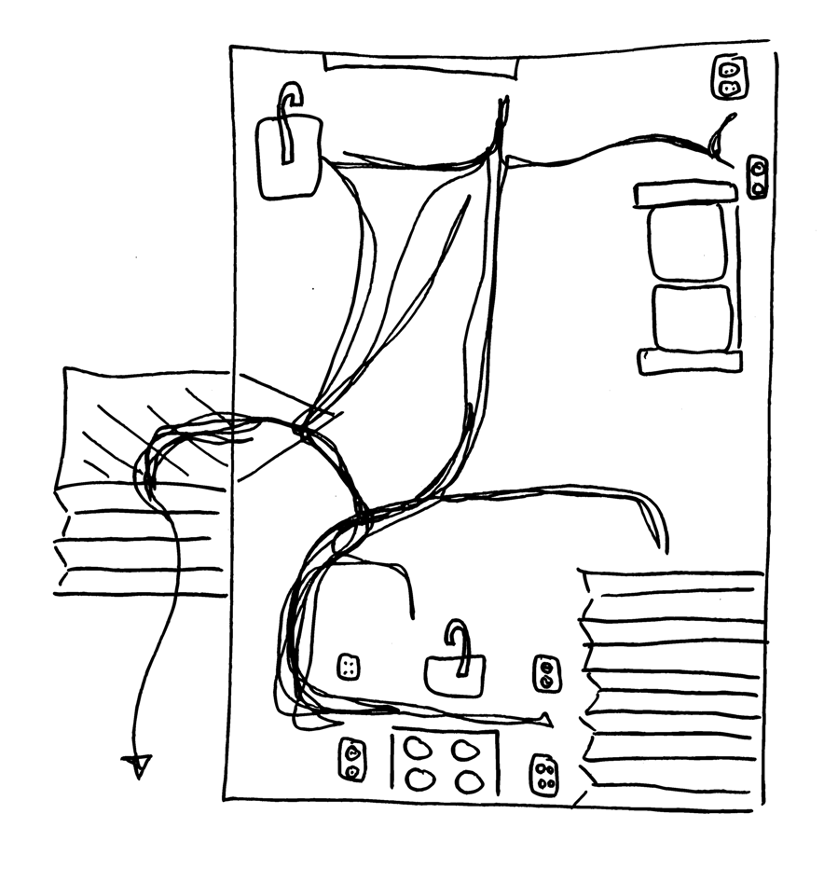

But first I want to talk about the art! Nearly a dozen line drawings are scattered throughout the collection. My favorite are the rudimentary floor plans (of a home, a place of work, a route to the bus stop) on which Jones has essentially created maps of OCD.

These visual poems (poems made of lines) are doing something different than the poems made of words. The language of the line is universal, and these drawings are immediately viscerally felt. One glance at “Preparing for Vacation” and the reader will recognize the lines traced and retraced over themselves as the multiple paths traveled by the compulsive checker and will feel the weight and urgency of those lines having grown thicker and darker as they trace repeated returns to the outlet behind the couch, the oven and the faucet in the kitchen, the locked door.

In the Spectral Lines Visual Poetry Chapbook, to which Jones is a contributor, editor Kyle Flemmer says, “Visual poetry radiates outward in all directions from the question: What does language look like?” The visual poems in Attic Rain seem to radiate from the question: What does OCD look like?

Meanwhile, the written poems, of which Attic Rain is primarily comprised, ask: What does OCD feel like? The most urgent portrayal of the felt experience of OCD is the poem “AN ALARM IS BEEPING SOMEWHERE IN THE HOUSE,” which is typeset in all-caps, in prose blocks that present like stanzas which grow lengthier as the poem moves down the page, becoming visually thicker and heavier as the anxiety about a beeping alarm becomes more all-consuming and untenable. It is a visual poetry of sorts, as well, mapping the increasing intensity that moves from the speaker’s initial attempts to identify the offending beep in the house to this escalation of fear in the final stanza-paragraph:

WHAT DOES A BLINKING ORANGE LIGHT MEAN? NO. NOT

THREE QUICK BEEPS. FOUR LONG BEEPS. AM I GOING

TO DIE? WHO WILL FIND ME? WILL THEY DIE TOO? TAKE

OUT THE BATTERIES SO I CAN THINK. TAKE OUT THE

BATTERIES. CONCENTRATE. I’M TRYING TO THINK.

SOMEONE TAKE OUT THE BATTERIES. THE BATTERIES.

So even in many of the poems made of words, Jones is also using visual cues. Several lines in the poem “How to Leave Home Three Times at Once (Refrain)” are typeset on top of each other so heavily, with such repetition, that they become illegible.

In an interview on CKUA Radio, Jones says, “I know I’m never going to give someone a poem and have them read it and say yep, I know exactly what OCD feels like.” But these moments in Attic Rain come close. When I read them, I feel trapped in a loop of obsession, consumed with overwhelm, unable to think clearly. Have I had these specific thoughts that Jones writes in her poems? Not at all. But when I have my own repetitive thoughts about the specific themes my OCD identifies with — car accidents and gun violence, for example — is this what it feels like? Does it feel like the certainty of reality and the doubt of OCD have written on top of each other so heavily, with such repetition, that they have become illegible in my own mind? Do I not become looped in doubt over whether I have turned off the stove but become so anxious at the possibility that a man is aiming his gun at my head just now through the window that I feel certain he is still there even though I have just looked and saw nothing? Yep, that is exactly what it feels like.

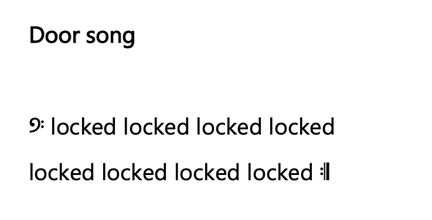

The poems in Attic Rain also ask: What does OCD sound like? In a wonderfully playful section titled “Incantations,” Jones announces: “I realized I was making music.” Poems in this section are titled “Kitchen Song,” “Door Song,” “Bathroom Fixture Song,” and the like. They are small musical compositions representing the rhythmic repetitions of compulsive ritual. “Door Song” includes the repeated “locked locked locked locked,” and “Garage Song” includes “shut shut shut shut.” She makes use of musical signs like the quarter note rest symbol and the repeat sign.

In these poems, Jones plays the soundtrack of her rituals, so that if a reader cannot understand what it feels like to experience OCD, they can at least understand what it sounds like to listen to the cacophony — the very music — of OCD.

What would my OCD sound like? To others, it would be silence. But the intrusive thoughts and mental compulsions are very loud inside my own head. I loved the “Incantations” section of Attic Rain not just because it’s such a cool idea — Jones is putting her OCD into the shape of a poem inspired by music that I never could have imagined — but also because I’m experiencing these sounds as somewhat of an outsider. The silence of my own OCD symptoms allowed me to hide for many years, for better and for worse — I avoided the stigma of sharing my diagnosis, but I also missed out on community, resources, and connection. I am curious about whether Jones’ different poetic choices are made possible by her lived experience with symptoms that cannot always be hidden, that her inclination as a poet to establish a pact of understanding with readers is perhaps owed in part to a certain bravery (if not ease) earned from years of practice in sharing that diagnosis.

I am struck by the poet’s inclination toward formal diversity throughout this collection. Jones makes use of traditional poetic forms such as the haiku and the villanelle and borrowed forms such as the “how-to” and the index. As I was writing Exploding Head, it seemed that only a single form could fit my lived experience with OCD: the thick, compressed, breathless block of the prose poem. Every poem in my collection is a prose poem because, for me, that was best way to put my repetitious obsessions on the page — in my own repetitious, obsessive, poetic way.

But Jones is interested in communicating something else about OCD, which is that OCD can be dynamic. The final section of Attic Rain, “In the Workplace,” opens with the line: “It’s fast-paced, challenging, and always changing.” This seems to refer to the environment of the shared office and scientific lab (Jones is also an Earth Scientist), but it could also describe OCD. It hitches itself to certain themes, and those themes can differ in response to your age or circumstances. OCD makes up its own rules, and it can change those rules at any time. If OCD can present in a variety of ways even to a single person who bears the diagnosis, it’s no wonder we so often fail to recognize our own diagnosis playing out in someone else’s life.

If there’s one experience of having OCD that we all share, it must be that of being misunderstood. When Jones has published poems about OCD, she often includes her diagnosis in her bio as a critical identifier — in fact, as a critical part of her identity. When poems from “Incantations” were published online at Blanket Sea, her bio began: “Samantha Jones (she/her) co-exists with OCD, sometimes more peacefully than other times.” Her Instagram bio currently reads: “Samantha Jones (she/her). Earth scientist. Writer. Editor. Calgary-based, Nova Scotia-born. Black Canadian & white settler. Attic Rain. #OCD.”

Including our diagnostic identities is a complex and relatively recent phenomenon (the discussion of which would consume its own essay). I have not included my OCD diagnosis in my own author bios or social media (except to refer to Exploding Head as an “OCD memoir”), but when I see it in others’ bios, I receive it like a small flag announcing membership in a diaspora of obsessive-compulsive lived experience, a warm hand reaching from its own isolation and offering to join mine.

And I understand it as an act of self-protection. Jones’ poems are often accompanied by identity signifiers, notes, and explanations. Attic Rain is bookended at the outset with the “Dear Reader” plea and at the end with a three-page Notes section of “behind-the-scenes” insights into the construction of her “OCD cartography.”

If it seems Jones is a poet who wants to preempt or mitigate the risk of being misunderstood at every opportunity, who could blame her? I have been misunderstood and misdiagnosed by readers, colleagues, friends, and loved ones. My “obviously OCD” visualizations have been misdiagnosed by armchair psychologists, and my all-consuming, primarily mental ritualistic compulsions have been minimized or dismissed. OCD is not a character trait or a quirk. It has nothing to do with desiring to be organized or appreciating a clean kitchen. Jones says it best, targeting the misappropriation of OCD head-on in the title of the poem, “Stop Saying You’re ‘OCD About It.’”

Ultimately, what makes us feel connected to others? Even though those of us with OCD share this three-letter acronym, we may experience wildly different manifestations of the disorder; in fact, we might never see the ping of recognition in each other’s eyes that says, I’ve had that exact thought. But we’re not just out here talking to each other. We’re also (and perhaps more importantly) making connections with those who might read our poems and think, I didn’t realize that was OCD! If we only go looking for ourselves in the pages of others’ books, we will never see each other. If we only sit in our own silence, we can’t hear the music others are making.

Jones’ final question (to readers, to popular culture, perhaps to herself) is “Can I leave things like this?/ Without being cured?” I hear it not as a dampened note tapping in a minor key but as a powerful major chord that hammers this musical collection of poems to conclusion on a confident note of self-acceptance.

Attic Rain opens with this statement of intent: “My aim is to share my vantage point and build compassion and awareness.” But if the author of a book about OCD has any responsibility at all, it is simply (though this is no small thing) to tell her unique story. Samantha Jones has done just that. And she has created a compelling, playful, and wise collection of poems in the process.

***

Attic Rain, Samantha Jones. NeWest Press, (September 1, 2024). 112 pgs.

dis/connect: OCD on Every Page: On Reading Attic Rain by Samantha Jones was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.