Diasporic Filipinx Archives as Spiritual and Poetic Sites: A Conversation between Amanda L. Andrei and Noelle de la Paz

Fellow writers and translators Amanda L. Andrei and Noelle de la Paz discuss their research and relationships with archives: Amanda with the development of her journalist mother’s correspondence into The Palangga Archives project, and Noelle with her repurposing of colonial documents to reimagine what is left out, obscured, or encoded within those records. From “inherited breakages” to “traveling gravesites,” this conversation aims to inspire audiences — especially from diasporic and Asian American communities — to consider how they (un)make personal and collective histories in (in)tangible, intuitive, and spiritual ways.

Amanda L. Andrei:

I’d love to start with our first encounter with archives of any kind.

Noelle de la Paz:

My earliest rememberings of that concept have to do with a box full of my lola’s old photographs. She died when I was in high school and I was digging through that box to put together a photo collage for her wake.

It makes me wonder about your experience with your mother’s archive. Can you talk about your work, and what brings you to this particular project, The Palangga Archives?

ALA:

I’m a playwright and literary translator, and I come to the archives at this time in a mindset of inheritance. My mother was a journalist in Eastern Europe, more specifically Romania, in the 1970s, and she had a lot of personal and professional correspondence from that time and when she came to America. As I get more into the archival space, I’m learning the specific vocabulary that belongs to that field. There are archives, but also collections, and what makes something a collection versus an archive is something I’m figuring out. As I get deeper into it, I’m like, ‘Oh, this is hierarchical, there’s a Western knowledge structure about how we experience and access knowledge.’ But I just call my mother’s stuff ‘archives,’ because some of it is organized and some of it is not, and it lives in this weird space. I have a background in anthropology, so her items resemble almost more of an archaeological site, where things get layered and layered and layered. That hearkens to geology, so I intuitively start connecting it back to land, earth, and family. Inheritance.

ALA:

Some of my plays have actually sprung from going through my mother’s work, and it became too charged to look at her papers in my home. I brought her items to another space where I could treat it as an artistic or professional project: I dress up, I have a uniform.

And so you’re a poet and a translator. What are you working on right now?

ND:

Most recently I’ve been working with colonial archives, the ‘master narrative’ that declares ‘This Is History.’ I’m slowly putting together a body of work around the archive — erasure poetry, experimental translation, prose. Maybe it’s a manuscript blending those forms with visual elements; maybe it’s something that gets presented in ways that go beyond the page. I’m still in the generative phase.

As part of the Filipinx diaspora, I’ve always had this feeling that our archive is elsewhere, or comes from elsewhere. Being born in the U.S., at first I thought, ‘Well, everything’s in the Philippines.’ Later, I learned that a lot of the colonial documents from the Spanish period are in Mexico, which was New Spain at the time, and a lot of the administration was through there. There’s stuff in Mexico, in Spain, and also here in the U.S. There’s a huge Philippine collection, oddly enough, at the University of Michigan Museum of Anthropological Archaeology. So if the archive is tied to a physical space, then Philippine history and its globalized (before that was a term) experience makes it really complex. Even more so since we work with digitized archives now, which is even becoming this other space that’s accessible from anywhere.

ALA:

What you’re bringing up for me is the physical conditions of the Philippines. I remember asking a professor about a particular subject in the Philippines. He said it was interesting but the archives in the Philippines were damaged, and the paper had rotted. It makes me think about humidity, the physical conditions of the Philippines that make it difficult for paper to survive; monsoons, and the Philippines as this disaster-prone land mass; how all that can be difficult for archival management. I’m thinking about my relationship with paper, the ways our ancestors accessed knowledge, and then the introduction of photography to the Philippines, especially as a colonial tool. I wonder: What would pre-colonial archives look like? How were our ancestors recording and accessing knowledge? Maybe more through objects, jewelry, gold, metal. And oral tradition, we’ve talked about oral archives too —

ND:

— yes, and how that oral aspect rejects Western ideas that dictate that the archive needs to be tangible. Oral tradition-as-archive or memory-as-archive, all these non-physical ways of how knowledge is passed down and recorded — those pathways, by virtue of colonization, diaspora, etc., are interrupted. There’s a tension because, on one hand, I know it’s a very Westernized categorization system. But on the other hand, that’s precisely how I, in the diaspora, I, with these inherited breakages in how ancestral knowledge was passed down, that’s how I have relied on getting some information. I do approach that information with scrutiny, I do try to subvert and challenge it, but it’s my starting point. What I have access to are these documents written by the colonial government talking about the Philippines as a possession. So, a) Fuck that. But b) I’m still going to it, and doing something with it, and engaging with it in a way that’s helpful to feel that through my work, I’m fucking with its inherent power structure. Or at least I hope to be.

ALA:

I love that phrase you used: ‘inherited breakages.’ That’s something I want to think about, because it’s also the spaces in between the words. All those breakages on the page. Our breakages with history and lineage. I’m thinking about it in the context of that AWP panel about errors that we went to. How can those breakages be generative or nourishing? How do we learn better? How do we keep moving from these spaces of error, or breakage, or inheritance?

ND:

And how do we stitch meaning together?

ALA:

As we’re talking about preserving and accessing our history outside of archives, I was thinking about other places where ink was used in the Philippines to record history, and perhaps without paper. For example, tattoos (and obviously not every tribe in the Philippines did this, some tribes and ethnicities have a tradition of it), but that became a method of historical record. So when we think about a body of archives, or a body of (artistic) work, we might compare it to ink and permanence on the physical body.

ND:

How we inscribe upon the body. Body of text. Body of work. The body as a text. All these different ways language has kept those two ideas close. The connection between physical space/body and archives/text. The distance that comes between those two things and how they’re always trying to find their way back. Whether or not the archives need a physical space; whether or not stories need a body.

ALA:

In the Filipinx diaspora, sometimes it feels like we have to go to all these other countries to see these things, or we have to understand these other languages like Spanish to understand our history more deeply. Have you been to the archives in Spain or Mexico?

ND:

Not yet. But I’ve been able to find stuff online. Mostly government documents and colonial records digitized by universities and institutions. Considering what’s accessible, that’s one reason I started there. Looking things up versus what’s passed down (or not) through family. I feel lucky, though, to have had access to bits of everyday ephemera in the house where I grew up in San Francisco. Starting with my mom’s grandparents in the ’70s, there was an accumulation of random stuff in that garage from all the relatives who stayed there. Growing up with a disconnect from where my family is from, there’s a specialness I’m inclined to assign to objects that are otherwise pretty arbitrary.

Asking about family history and culture can be charged. Immigration is in essence a story of breakage, and breakages are often unspoken. But when I pull up a historical document, I can have a conversation with it that’s less complicated, less intimate — less embodied, maybe. There’s the text, and then there’s me. I can imagine into the space between. The stakes feel different when writing personal family histories, with the fear of (not) getting it right, with all the things I can’t know.

How has it felt to treat your mother’s things as an archival project in its own right, while also acknowledging its personal significance?

ALA:

There’s something about going through the personal and family stuff that’s scary, because you’ll recognize yourself. Or things will float up that are way too personal and you’re not ready, like finding photos of my lolo’s funeral. Going through official documents is the way to keep that distance. It gives you a sense of training or practicing.

I started volunteering at an archive to understand how archivists work, see what their spaces look like, and get practice with something that is less charged. I currently volunteer at the Center for the Study of Political Graphics, and I’m helping catalog their Philippine section. I’m going through all these Philippine political posters and some are really intense, but it’s helping me practice going through my family stuff and also contextualize what my mom would have been going through or seeing.

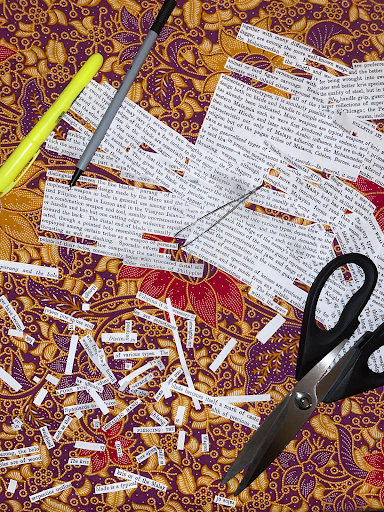

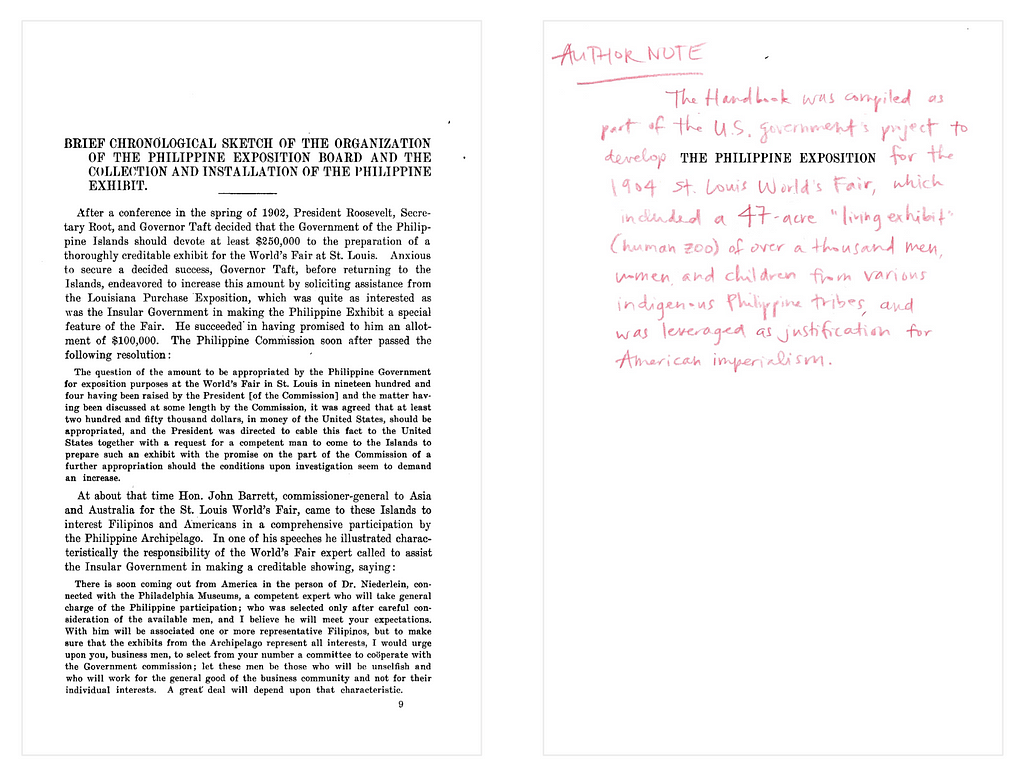

I would love to hear more about your specific poems. Could you talk about the inspiration for “Uncontainable Topography” and the choices behind making the process video?

ND:

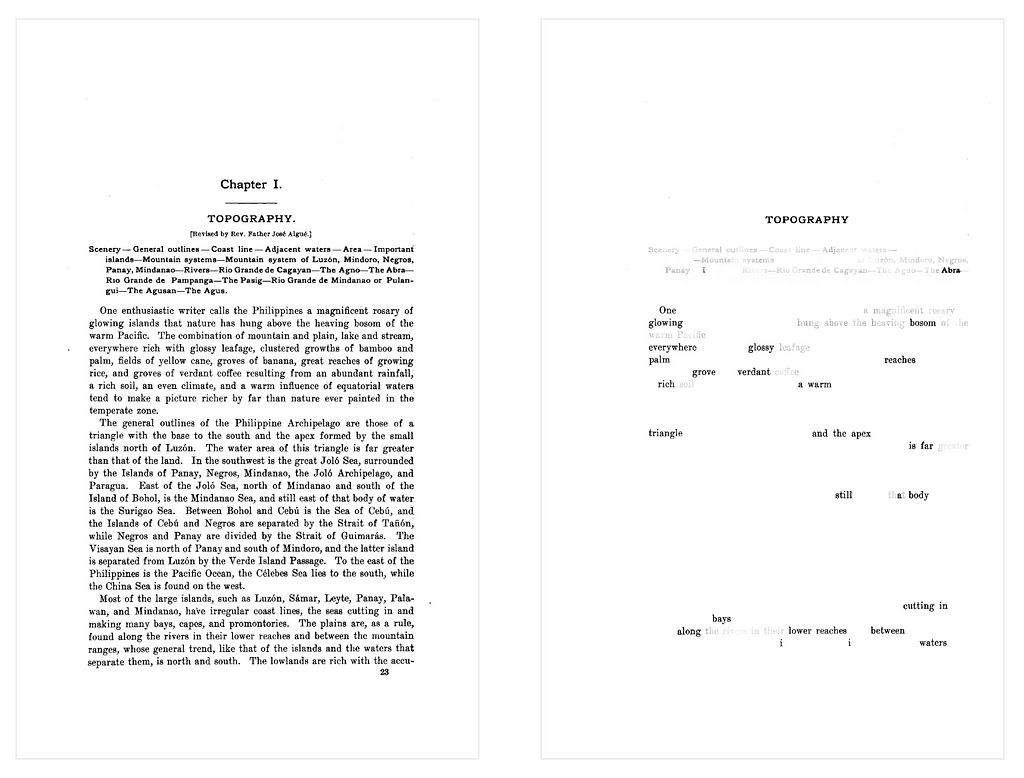

Approaching erasure explicitly through the lens of a power structure, there’s a reason why you’re choosing a text, going in and erasing parts of it — you’re enacting erasure upon an oppressive narrative that has itself enacted erasure or violence upon a people, place, culture.

So out comes this poem, characters emerge, and I keep thinking about how this iteration on the page doesn’t really give a sense of the hours I was immersed in this text, scouring it for something even when I wasn’t sure exactly what I was looking for. Because of the nature of the text, it takes a toll. You’re deeply entrenched in this document about the land and the people, written in this really objectifying way. I wanted a version that included the element of time, so I put together the process video. It’s just a couple of minutes long, no sound, but it slows you down and reveals the different levels of erasure. It was my attempt to have someone spend more time than it would take to just read the poem, to have a moment with the original text and literally see that master narrative falling away.

ALA:

Wow! The element of time. And how do the characters emerge? How do you start seeing them?

ND:

The chapter I pulled from is the topography of the Philippines. So I’m thinking about how land is feminized, stripped of agency, especially in colonial and military contexts. And I’m thinking about land as body. And so a body starts to emerge, and another one. There’s a yearning and a finding. These two characters start to form, flipping this colonial text into a story of their own.

ALA:

That’s so cool. And what a cool experimental translation exercise — if you give everyone the same text and see what happens, do other people also have characters emerging?

ND:

Absolutely. For me it’s really about the process. What comes out when you look at that chapter? What if you take another chapter? I’m interested in that as the work. This particular poem is just one version that came out for me at that one time. If I did it today, would a different story show itself? I’m interested in that type of meaning-making where I’m driving, a bit, but it’s also intuition, it feels random but is maybe guided by some other less tangible logic.

In The Palangga Archives, you touch on original order, which brings me to this idea of categorization versus what may look like random order, archive-as-oracle, intuition. What are your thoughts on how we locate what we’re looking for, or how we don’t know what we’re looking for until it shows up?

ALA:

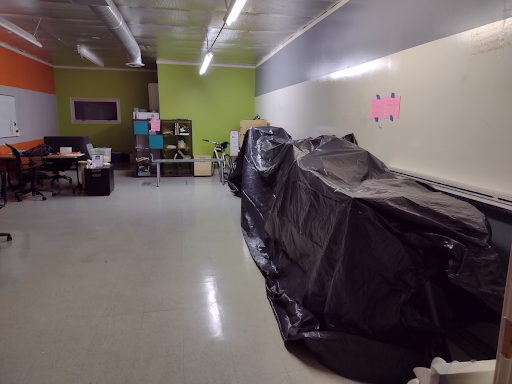

This is a good time to do a little virtual tour. The space is so temporary because I moved into this space around mid- to late January, and I’m out by the end of April.

There’s a bit of a library, in the furniture structures that were already here.

I’ve also been sorting photo albums. The album has become another artifact too, because I find myself wondering things such as, who composed this album, what guided them to where they put the pictures. This album is of my aunt’s funeral in the nineties — she got an album, but some of my other family members who passed away did not, or at least, those albums aren’t here.

And so here’s the big stuff —

I covered this because there was a leak a little while ago, and I didn’t want anything to get hurt. When I first moved in here I didn’t cover anything.

So let’s see if I can —

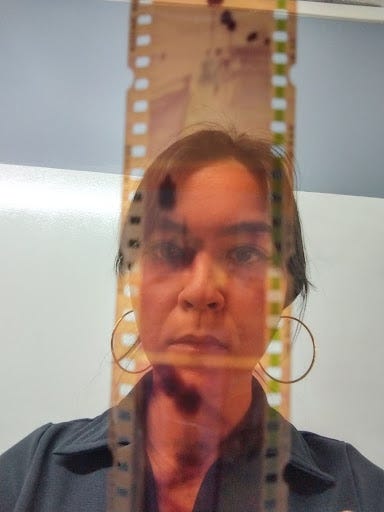

ALA:

See how it’s like a body.

ND:

I was just thinking it looks a little ominous.

ALA:

I know, it’s really intense.

ND:

Again: a body.

ALA:

And here’s my mom’s stuff, and my stuff. I’m finding these old pictures from high school, and I have to make choices about what belongs and why. That’s also a difficult thing. There’s something about this stuff, too, that is performative.

Here are folios that my mom had. All these carbon copies. My mom would just type everything and save it.

And this letter is from my Lolo. They would just save everything.

I also have 3D artifacts, like my mom’s handbag, some jewelry, and her eyeglasses.

Then it gets into mixed media and multimedia. I have video tapes of historical Asian American events from her time as a reporter in Virginia; floppy disks that take a whole other form of digitization and a lot of time and technical knowledge.

This is my inheritance.

ND:

Can you share a bit about what you do there?

ALA:

A lot of archivists have been asking me, ‘What do you want from this?’ And it changes. It’s become a moving target. Short term, I just want to know what’s in it, so there’s a lot of sorting and seeing what’s here.

A curator friend and I hosted a small brunch with some other Filipinx artists. We ate in the other room, and then came and looked at the archives. It was a really powerful experience having other people go through it. Something else that came up was this idea of food and archives not mixing. The fact that you have a brunch and an archive is already kind of a weird thing.

I think about how in the Philippines and Romania and other cultures, people go to a cemetery, have a picnic, visit their family, and can visit the body or bones — and ultimately the spirit and soul — in a physical place. This archive has become that for me.

Being Filipina in the diaspora, with my mom passed away, this area has become like a memorial or a gravesite for me. It could be a traveling gravesite, whatever that means.

ND:

The Westernized notion of the archive is that it’s very static, yet everything we’ve been talking about is contending with that as an unnatural state for memory, for identity, for home, for physical spaces. All of those things are constantly morphing and evolving and changing. I think a lot about how the Philippines is thousands and thousands of islands, and how fragments come with a negative connotation. Yet some of the most powerful experiences are about finding and fitting pieces and making meaning. And that meaning can change.

As we planned this conversation, one of your questions was: how do our emotions and personal histories change as we engage with archives and how do these archives change in response?

Archives responding and changing feels antithetical to how archives are supposed to be fixed so that people can find exactly what they’re looking for. But when you don’t know exactly what you’re looking for, being open to different kinds of order and organization actually feels closer to the essence of what it is to collect personal and collective histories.

ALA:

I tend to think of archives in the same space as libraries and museums. They’re open to the public, and I realized, why don’t I visit archives as much as libraries or museums? Digging more into archival principles, there’s also this idea that there’s only one copy. You can’t really replicate it in the way that you can have lots of books across libraries, and how museums can bring things out and put things back in this wide exhibition space. In archives it’s like, this is for research, and this is the one thing, so you can’t mess with it, you have to be tender with it. And I connect that to gravesites, because when you go to the tomb you obviously don’t mess with it. I haven’t fully fleshed out what that connection means yet, but I had a friend tell me, ‘You can be a little rude with your mother’s stuff, you can be a little rude with the archives.’

ND:

It’s that preciousness, right? When you’re coming to something that feels like you can’t get anywhere else, then of course it’s precious. But also, can we get this elsewhere? Or, why do we feel like we can’t get this information or this stuff elsewhere? Can we locate things as they are moving?

I was so taken by your traveling gravesite idea. It speaks a lot to what it’s like to engage with archives from the diaspora, with both the specificities and the unknowingness. We’re clearly looking for something. Archive-as-oracle is about coming upon things by chance. As in, this photo of my grandparents underneath this tree with this inscription on the back — I couldn’t have told you that’s what I was looking for, but when I picked it up I knew that’s what I was looking for. It’s different from going to a library or museum or archive with a categorization system that, sure, is helpful within its own logic. But you don’t know what you don’t know.

ALA:

Yeah, I’m really obsessed with the idea of the archives as oracle. It’s almost like the archive is looking for something, as if it has some kind of spirit or soul, or knowledge, or information that needs you, the visitor. It needs you to impart it, take it out into the world. Especially with this collection, it feels like it’s also looking for something.

ALA:

I ended up writing a couple of plays based on stuff I found from it, so I wonder. There’s something about this archive that wants to be seen.

And other archives or collections, what do they want? And the bureaucratic texts that you’re working with, what do they want? What’s behind the bureaucratic text that wants to come out through another person?

ND:

Some poetic forms I play with are inspired by codes and cryptography, which I was really into as a kid. I loved the show Ghostwriter. How clues could feel dynamic and alive, unseen presences trying to help us solve mysteries. Stuff you have to dig for, stuff you have to decode. Stories that for whatever reason couldn’t come out in full, but have been dormant, or are in there in some way and just need us to meet halfway, partway, whatever.

ALA:

It’s like they’re sleeping, and they want to wake up and talk. But they need another person, a living person, to help them — or, not to help them, but to interact with them.

ND:

Time has to fold, to align two disparate points on the same plane. To activate.

Diasporic Filipinx Archives as Spiritual and Poetic Sites: A Conversation between Amanda L. was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.