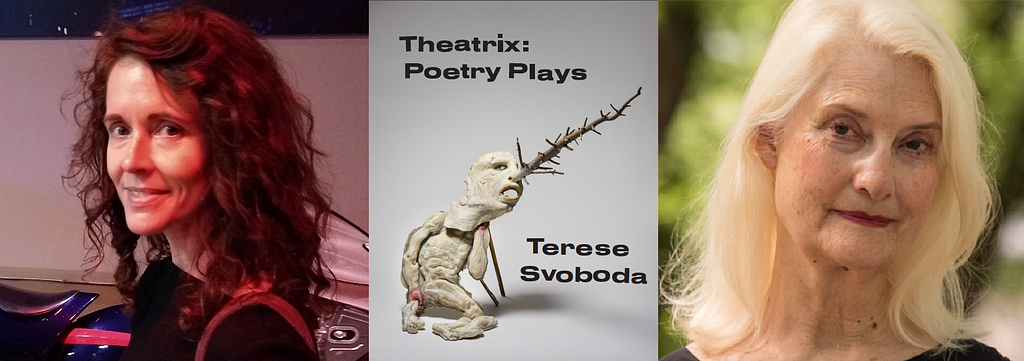

THEATRIX: Karla Kelsey & Terese Svoboda in Conversation

Karla Kelsey: The title of your new collection, THEATRIX : Poetry Plays acts as a seven-syllable poem emblematic of the wordplay that animates the book. “Theatrix” puns on “theatrics” and is a portmanteau of “theater” and “-trix.” “Trix” as a suffix does the job of turning masculine agent nouns feminine (e.g. aviator, aviatrix). As such, “theatrix” not only re-hears the last syllable of “theater” and gender-switches it, but it also renders theater… well… performative — an agent of action! But the play doesn’t stop there: “trix” yields “tricks” as “poetry plays” at the genre of drama. As I write to you about “play” I realize I haven’t even mentioned the phrase’s alliteration, rhythm, and the typographical balancing act of the semicolon.

What a delightful, elegant, kinetic construction! Throughout the manuscript moments like these are both cerebral and physical. Is your composition driven by conscious thought, lyric impulse, or both?

Terese Svoboda: I rely probably too much on the lyric unconscious, whimsically assuming that the efforts of revision will skew whatever interesting musical item I’ve managed to produce into some kind of coherence. I guess I assume that the unconscious has coherence, the way I assume whatever outfit I buy in whatever color matches everything else because there’s only a few shades being sold at any given moment. (Did that analogy make sense?) Line rhythms and spacing have to be deliberate, both aural and the page, so that requires coaxing. Associations accrue. That jaw-dropped moment just before or after sleep is where poems begin to dance in my head, and luckily we’re all wearing masks the rest of the time.

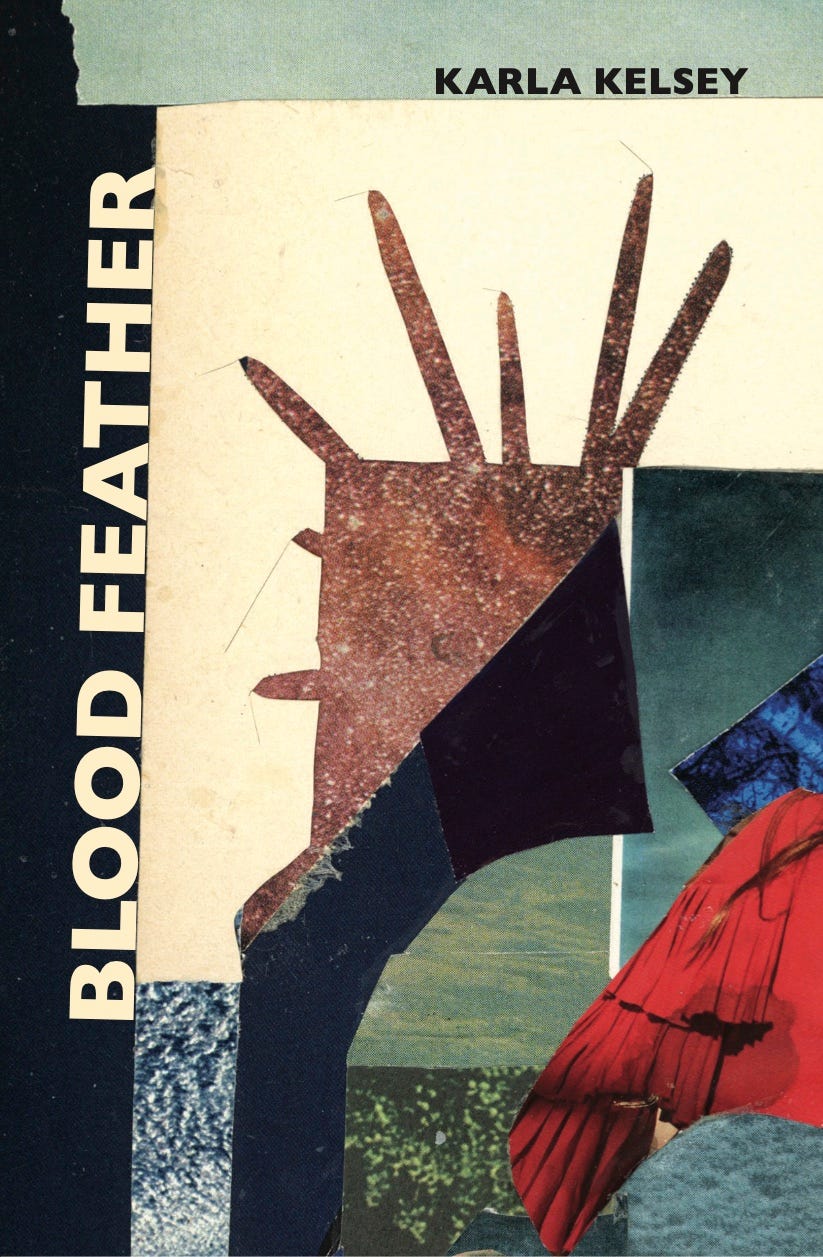

Blood Feather, a book that swoons with theatrics different from mine (shall we say “chimes?”) from theater and film and architecture, but before I nuzzle into that, let me have a go at your title. Its first appearance warns the reader: “if a blood feather breaks you must pull/it immediately stop the bleeding.” So terribly evocative. As you say at the end of the collection, Blood Feather began ten years ago while writing a six-sentence dramatic monologue. You then wove the sentences into locus points of cultural or personal narrative. My question is whether all the germinating sentences remain intact in the poem? It would be interesting to see the sketch that drove the work and know whether those feathers were there from the first.

KK: Germinating sentences remain but are altered through a process of weaving the strands of each poem, as well as snipping and stitching the prose into six-word, six-line stanzas. What most remains for me, as origin points, are the three speakers who animate the three dramatic monologues composing the book. If a sketch exists it is a large, handmade map pinned with photographs of these three women as they move throughout architectural and natural landscapes.

On the subject of character: THEATRIX begins with a cast list that includes the fundamentals of many narratives (“You,” “Me,” and “We”), as well as recognized figures (“Poe,” “Debussy”) and surprising entities like “Set” and “Not to Mention.” These characters float through the book, as do characters from Shakespeare along with historical figures like Emma Goldman and Helen Jewett.

This list expands my sense of who and what gets to be a character — an agentic entity with the capacity for language — and creates a highly animated world where even cutlery has something to say. This doesn’t so much displace the human as show the human to be deeply woven into the fabric of material reality that includes the human (but is not solely devoted to it). For example, in “Blank Pink Mall,” Edward Hopper’s wife enters two-thirds of the way in, which both shocked me and felt inevitable… the pink she wears in his “Morning Sun” always had been in the poem, from the title and the first line “The color of pretty” to the “pink petticoat, / ripped, with a safety pin/ pinned to skin.” As you so pointedly write “it’s not a color, / it’s a code.” A code for the body, for femininity, for domesticity, for commodity, for violence…for these things as they constitute (in particular) the white, American middle class. To what extent do the poems of Theatrix originate with specific characters in mind — unfurl from them and their literary/historical contexts? To what extent do the characters enter the poems almost by surprise?

TS: I have so much to discuss!

Only in “Emma’s Play” did I set out with an actual character. I’d had a lot of contact with Emma while writing my biography of Lola Ridge, and her throbbing ardor for freedom, once known, does not die easily. I needed her comically dead to even approach her. The coincidence of the usher being linked to Poe’s tale was too much for me to resist, then when I discovered that Debussy hadn’t quite finished the opera based on his story — well, he had to make an appearance too. I labored hard to link the cause of his death — cancer of the colon — to an opium habit but that didn’t pan out. “An Audio Tour of Helen Jewett’s Murder in Downtown New York City” is derived from my project of the same name that was refused production because funders didn’t want users to know (ten years ago) that they were being monitored by their cellphones. I’d read Patricia Cline’s biography of Helen Jewitt about the same time O.J. Simpson got off and was struck by the parallels of injustice. With regard to Shakespeare, aren’t his characters mostly adjectives now, Falstaffian, Hamletesque, Cesarean? Just kidding. It does seem to me, however, that they’re ubiquitous in how we talk about theater and its trappings, and that everything theatrical resonates against his creations. Hopper’s wife was indeed a surprise that fit.

I suppose the recognition — really Buddhist — of the animation of all things stems from the sixties book, The Secret Life of Plants, augmented by the more recent efforts to artificially animate everything with AI. The pandemic seems to elicit even more identification with the life force of my surroundings, as I negotiate my loneliness.

Question:

How our books are so attuned! By line three, when you use “elicit meetings” rather than “illicit,” I began to nod. Here’s someone who knows their way around the monkey business of words and attention. Then the persona layers her experience with the seductive Hadley by practicing lines from “The Glass Menagerie!” How soon the poem inserts the whole world: “oh how those minivan angels/ their babies buckled into safety seats/envy me.” From Williams’ drama to Maya Deren’s movies to Stravinsky’s music, even through architecture, with Le Corbusier defacing the work of his rival, Eileen Gray, by frescoing the side of her building, you manipulate poetry’s page-bound theater, opening it beyond the speaking voice, beyond language games (but not abandoning them), going for the fictional that, paradoxically, tells a new, and very interesting truth.

But the question! Were you influenced by Ammons? I hear a bit of Tape for the Turn of the Year. I’m not suggesting it was written on adding machine tape, but I’m very intrigued by how you move from subject to subject with such fluidity, despite your formal constraints. Was the poem written in sprints and then revised, or was each section planned separately? The rupture of the numbered “parts” that occur mid-flow of each long poem sometimes divides the waves and sometimes causes them.

KK: O, ideal interlocutor, how much your mind delights, both with your published pages and the flash back-and-forth of this interview. The book-length poems of A.R. Ammons are certainly an influence. But prior to knowing him, Louis Zukofsky’s A, and the counted verse patterns that pull through that magnificent book and, as he says in Prepositions: “the detail, not mirage, of seeing, of thinking with the things as they exist, and of directing them along a line of melody.” Add to this the great feminists of invention, who understand the life-and-death significance of mirage: H.D.’s Trilogy and Helen in Egypt. Alice Notley’s Descent of Alette.

Blood Feather is in thrall to constraint-based form’s power to elicit something new not only from me but from the materials — language, narrative, research, invention — of the work. In terms of process, the book evolved via form, and then by rewriting each of the three long poems more times than I can remember. I began by applying the weaving pattern of the sestina to blocks of prose, worked those into six-word, six-line stanzas. The numbered parts mark where each ur-sestina ended and the new one began. Blood Feather’s rupture and flow is perhaps similar to what happens when the last word in a sestina’s stanza is repeated as the last word in the next stanza’s first line.

What you playfully say about Shakespeare’s characters becoming adjectives is so true! And THEATRIX is very attuned to the ways in which one slips in and out of artifice, character, type. A woman at the window. A woman at the mall. A woman leaving lipstick traces on coffee cups. A woman in the guise of “dog with glasses on her muzzle.” A central drama of the book — its rupture and flow — is the movement in, through, and out of stable positions. I find it so fitting that elements of dramatic writing (like interruptions or asides formatted inside brackets and character names cast in majuscule) punctuate but do not dominate the book as the work slides in and through poetry and drama.

How did employing formal elements of dramatic writing come into your process? How do they play into the way the book works with figures abandoned by history (the unfinished opera, Helen Jewett) — or just at the outside of other projects?

TS: Majuscule! A new word! Kind of majestic and miniscule meaning, with irony, ALL CAPS.

Pound told Louis Zukofsky to look up Lola Ridge to find out what was going on in the poetry scene in 1928. That’s about as close to Zukofsky as I’ve ever been, but now I’ll have a look. H.D. always seemed so bloodless — I read something the other day that suggested that her reliance on Bryher stunted her work (how do they figure things like that out?) and I don’t know Alice Notley’s work very well at all but now she intrigues me. Your intricate weaving pattern is so graceful I never noticed it! Brava!

“Always entering or exiting the liminal has something to say about female relation to roles” is very provocative. Do you mean how women, relegated to the sidelines, have to pretend not to be the prime movers? I’m writing a memoir called Hitler and My Mother-in-Law who was a war correspondent in WWII and accomplished many amazing feats but was commended by her peers as being able to manipulate men, so they were not offended by her achievements. Something like that?

My question: You “make a little/ tune of pine rising salt in/ the mouth full in the ear” but there’s also an actress in the poem, “a woman standing/ at the window necklace glittering the/ plunging neckline of her gala dress” who (if I can be so bold as to unite the third person with the first) “wonder[s]/ is it like to feel oneself/ to be a body created for/ hunting capturing imprinting.” She transcends the role of human, that is to say, nuzzles animal and spirit and mind in off-the-page ways, making the dramatic event of the poem resonate on so many levels. “To perform a woman possessed is to transform into a woman/possessed” — does that refer to poets as well as actresses? Have you heard of the work of the sociologist Harold Garfinkel? He hypothesizes that we are always performing.

KK: I haven’t heard of Harold Garfinkel, but I will certainly look for him, as I am taken with the idea that we are always performing. On one hand this might seem anxious, as if we are abandoning our authentic and non-performative self. But who or what would that be? Instead, “the self” might be created in the act of being with others, in the act of being in context, in the act of languaging. Judith Butler, Elizabeth Grosz, and Carla Harryman are thinkers I’ve gone to for ideas about performance, gender roles, and language itself as a character. Working with persona has amplified my sense of language as transformative performance.

In terms of the liminal, I was thinking of the ways in which women might of necessity be more aware of the artifice of roles, given the limiting roles we have been historically assigned — as you have said, speaking from the sidelines, giving credit to male movers. It would make sense that women would shape-shift in and out of such roles, pragmatically, and by necessity. An awareness, too, that one is not always a singular thing, although female roles often seem to be designed for full-force identification with no room to maneuver.

My question:

Hitler and My Mother-in-Law, sounds fascinating, as is your biography of Lola Ridge — perhaps both feminist reclamations? I’d also place THEATRIX as a feminist text. Part Two abounds with fathers, features them in poems with titles like “Dad or God,” “King Leer,” and “Dark Daddy.” So much tragedy happens in Part Two, and here I read these fathers as family-fathers and the institution of patriarchy. The book ends with the “House of Atria,” which is infused with Greek tragedy and suburbia, finishing with “Two men” who “force/ their way in, amulet-heavy” and “A prince/ disguised as a shepherd” who is pursued by a bear as he exits. I can’t help but to read this through the context of our current moment — our current leadership, the current state of what used to be referred to without irony as “Western Civilization.” To what extent is Part Two a response to patriarchy and the decline of our times? What role does “feminine” and “masculine” energy play in the drama of the work?

TS: Masculine and feminine are universal energies that all humans balance: assertiveness vs. passive, caring vs. indifference, intuitive vs. logical. Tension produces progress. Without it, we are in the forever now. But testosterone is winning at the moment. Yes, women aid and abet the patriarchy but who has had the last word all these centuries, who wields the power? If gender is performance, Dad’s hogging the stage.

Thank you so much for your nuanced analysis of shape-shifting. It seems, as females, we’re uncomfortable. My fourth book of poetry, Treason, newly re-released by Doubleback Books, looks closely at the betrayals of the family where we learn our “place,” the mother-father-child triangle in tension. A rhetorical question: Has the pandemic strengthened this tension, as we stay inside, family-bound in our bubbles?

My final question for you: Blood Feather is a seamless cloth woven of Penelopes. Its periodlessness creates juxtapositions that press the reach of metaphor: whole parts, whole stanzas. You go much farther than the mere presentation of drama, you say “let us be the aperture,” the title of the last section of the book, where, instead of unraveling, it unreels, with filmmaker Maya Deren at its core. Then, at the very end, you list the texts that influenced the book, but what makes sense of them is the deft presence of the persona linking us to the present. Less loftily: In the aftermatter, I see that the last section was previously published under the title “Sestina LA.” What happened to that scaffolding? Did you write senstinas and then take them apart?

KK: I very much like the word scaffolding: a structure built for building a structure. The sestina continues to scaffold all of the book — but as a pattern of paragraph-formation, improvisation, and weaving, rather than the way sestinas usually work, as a pattern of stanza-formation, repetition, and weaving.

To build each movement of each of the three long poems I began with the six-sentence paragraph, then took each of those sentences and wrote five more through a process of research and improvisation. I then wove each of the six paragraphs into each other using the sestina pattern to select where sentences slotted in. I then edited those paragraphs and began moving them into the counted verse form (six-word lines, six-line stanzas), editing and removing punctuation as I went. The material for many of the paragraphs came from research, but not all of it — there is invention and improvisation, too. In a few places I shifted or tweaked the order of things for the good of the whole, understanding that what mattered for the poem was a sense of dynamism, weave, and return (while fraying and advancing). What shifted most from the “Sestina LA” version to Blood Feather’s version is all revision and reworking, rather than structure. All-in-all the process was a method to feel my way through the dark. The process also might be a metaphor for a dynamic of freedom and inheritance, which is part of how one makes — might make — a life.

My final question for you is process-based, future-looking, and perhaps a bit selfish: I love to (as they say) pick your brain. Your body of work is so expansive: poetry, story, novel, memoir, translation, and biography as well as the interdisciplinary libretto and video work. While themes trace through, each project is a world unto itself. Do you often work on several things at the same time, and does your process differ greatly from project to project? What world did THEATRIX come from, and what has it led to — or do you see projects as having separate sources?

TS: And I thought sestinas were all about repeated line endings! Freedom and inheritance, a wonderful way to describe mitigating the formal. And feeling one’s way through the dark — I often think of the cartoon character sawing off the branch he’s standing on, about how long he swivels his head in amazement before the branch drops.

When I am frustrated with one project, I pick up another. This is dangerous with a lot of pages, since bigness involves memory, at the very least, to avoid repetition. then there’s the teasing forward of narrative links which, unless there’s a big POW! on the page, are easily woven under by some distraction. But what’s a woman of letters to do? I’ve just been given a commission to write the lyrics for an opera about the Harlem Renaissance and I still have several weeks of work left on Hitler and My Mother-in-Law, a memoir I’ve been writing for the last two years. I can only sneak little video peeks at Cotton Club chorus girls while I chase footnotes and errant scenes for the other. And, as I mentioned, Doubleback Books has just reissued Treason, my fourth book of poetry. Doing the galleys for Theatrix: Play Poems at the same time as the other gave me ideas about where I was going back then, and where I am now. In the late seventies, I took a class with Marilyn Hacker, and under the severe formal constraints for which she is famous, I discovered that voice-driven poetry was too confining to be truly authentic, at least for me.

I too have very much enjoyed our exchange. That we find resonance in each other’s work is heartening, given the confined context of the times. The lonely page does not turn on its own.

Theatrix: Play Poems is Terese Svoboda’s eighth book of poetry. Treason, her fourth book, has just been reissued by Doubleback Books as a free pdf. A Guggenheim recipient, she has won the Iowa Prize in Poetry, the Cecil Hemley Award and the Emily Dickinson Prize from the Poetry Society of America, and a New York Foundation for the Arts grant. Also the author of seven books of fiction, a memoir, and a book of translation from the Nuer, she published Anything That Burns You, a biography of the radical poet Lola Ridge in 2016.

Karla Kelsey is a poet, essayist, and editor. Her writing often uses the lyric form to investigate the philosophical and historical. She is the author of one book of essays and three poetry collections: A Conjoined Book (Omnidawn, 2014), Iteration Nets (Ahsahta, 2010), and Knowledge, Forms, the Aviary (Ahsahta, 2006) selected by Carolyn Forché for the Sawtooth Poetry Prize. Her fifth book, Blood Feather (Tupelo Press) was just released this year.

THEATRIX: An interview with Terese Svoboda was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.