Arturo Desimone’s series on Latin American poetry for Anomaly poetry review.

I used to believe the Hebrew Song of Songs, that “Love is a force Stronger than Death.”

In Argentina, where there seem to be millions of Jews, I tried to somehow reenter the religion of my birth through fissures of stone that no longer allowed reentry, under the patter of soft woven sandals of Jewish women, after decades of estrangement from my religion and its practitioners. The men in their thick black suits in the December heatwaves of Buenos Aires, their hats of mystic rectangles; the Orthodox women always in their long skirts from a long forlorn Mediterranean, walk down the streets of El Once and Villa Crespo, the helmets of their wigs at times shining, other times under thin scarves, remind one who read the Song of Songs, originating in a poet from a society of Bedouin and goatherds, with his lines that compare the lovers teeth to a flock of sheep, freshly shorn, coming down a mountain after having frolicked in the pool at the rock enclave of a morning-clad mountaintop. Only the filthy sidewalks of Buenos Aires do not look like a slope washed by the flash-flood racing into a wadi below.

Lines of irritation wove a web in the face of a Rabbi of Buenos Aires when I asked him about the love in the Song of Songs. Taking me for a lecher and vagabond, suspecting my reasons for being curious about the religion I seemed to have strayed so far from, he straight-off condemned me “This song of songs is not about amor. Not about what you call amor” his feet almost twisted in the grey tubes of his trousers ( heavy and stuffy as old factory curtains, packed with allergens that kept their wearer tormented with rashes) under the table, his irritated tone clearly showed he assumed I had said what I did not know I had said, that the ancient Biblical song spoke of an erotic love, a sexual love. I would not get it through my skull that the love spoken of in the Shir Ha Shirim, the Hebrew Song of Songs, and in other works, is, according to the religious authority, an abstract love, a bodiless love for “Hashem,” a love that is a condemnation of earthly love, water to its flame. More agape than eros: utterly impersonal, airy and metaphysical.

But the clear, direct references to eroticism abound all over Solomon’s song. Traditionally attributed to the Biblical Solomon who serenaded to a Yemeni or African noblewoman, they maintain that like Homer the poet’s true identity remained obscured by clouds of myth-history and was perhaps more than one single poet. Perhaps poets cannot afford to say that Homer never lived, and if so then maybe they should insist, as a zealot would, that Solomon wrote the entire poem. Verses compare breasts to apricots, or lines like the 13th

My beloved is unto me as a bag of myrrh, that lieth betwixt my breasts/ (יג צְרוֹר הַמֹּר דּוֹדִי לִי, בֵּין שָׁדַי יָלִין.)*

Your breasts are two fawns

twins of a gazelle

grazing in a field of lilies.

*And elsewhere (in a more recent translation by Chanah and Ariel Bloch)

Later rabbinical commentators and talmudists tried to encipher the fawns as metaphors for Moses and Aaron — an interpretation dismissed and rightly ridiculed by more recent translators, who claim the poem is like Ancient Egyptian erotic poetry and pertaining to a secular usage of the ancient past. (Perhaps here originated the divide between ‘’interpretation of art’’ and ‘’erotics of art’’ spoken of by Susan Sontag in ‘’Against Interpretation’’)

Lines like (the Blochs’ translation, quoted in a 1998 NY Times article “Putting the Sensuality Back in Solomon’’)

The joints of thy thighs are like jewels,

the work of the hands of a cunning workman.

Thy navel is like a round goblet,

which wanteth not liquor

were further diluted and truncated by the protestant renderings of the King James Bible.

The more direct, and irreligious translation by Chana and Ariel Bloch resorted to the Leningrad Codex, oldest known manuscript of the Hebrew Bible, in search of a revolutionary new translation to restore the ancient carnality (as Rubén Darío, Nicaragua’s own 19th century Solomonic patriot would have rapped time and again of “divine, splendid carnality of woman” without allowing anyone to interpret heavenly allegories).

According to English professor Ariel Bloch, a cultural period of disgust with the body besetting Judaism led to a more puritanical hermeneutics (hermeneutics os the religious ‘science’ of interpretation, used in Judaism after the encounter between Jewish philosophy and Aristotle).

Later on, the appetite was once more edited out or truncated by Protestant readings of the so-called “Old Testament.” Non-Jews seeking a christian liposuction of poetic fat, wanted to believe that the allegory coexisted with a puritanical injunction to a pure, disembodied love. But when the Italian radical inventor of the opera, Monteverdi, used the Latin translation of the Song of Songs, the Vespers, in his “Teatro de Amore,” he brought the song back down to earth from that heavenly alcove where thieves had hoarded the stolen serenade, and used it in the inherently vulgar art-form of opera. (In its Italian origins, the opera was a popular art form, only transformed into an elitist pastime during and after the time of Richard Wagner, whose ideological commitments are well-known).

Elsewhere the poem claims that the power of such eros-love is a deadly force mightier than death in what it forges. “Love is a force stronger than Death” I believed.

There are those who attest to the contrary — who will sing against that goatherd bard and say that love is simple, and devoured quickly by the jaws of time.

The text below, sung with bitterness by vocalists like Argentina’s Mercedes Sosa and the Mexican Costa Rican singer Chavela Vargas, expresses a state beyond “agape and eros,” in the pedestrian verse of songwriter Armando Tejada-Gómez.

In the video, Chavela Vargas appears, just before her death in Cuernavaca, sunglasses on the splintered face, the drought after alcoholism worn on the cured, in her shoulders abreast the dark hovering of a condor. She sings a popular and simple song, of no stature that could hope to ever rival the complexity and layered beauty of the ancient Semitic poem explored above.

Canción de las Simples Cosas (Armando Tejada-Gómez)

Uno se despide insensiblemente de pequeñas cosas,

lo mismo que un árbol que en tiempo de otoño se queda sin hojas.

Al fin la tristeza es la muerte lenta de las simples cosas,

esas cosas simples que quedan doliendo en el corazón.

So insensibly does one do away with small things,

same way a tree in autumn time remains bare of its leaves.

In the end sorrow is the slow death of these simple things,

these simple things that stay to ache the heart.

Uno vuelve siempre a los viejos sitios donde amó la vida,

y entonces comprende como están de ausentes las cosas queridas.

Por eso muchacho no partas ahora soñando el regreso,

que el amor es simple, y a las cosas simples las devora el tiempo.

One always returns to the same old places where one loved life,

if only to understand, what beloved things are now absent.

So boy don’t you part now, dreaming the return,

for love is that simple, and time will devour the simpler things.

Demórate aquí, en la luz mayor de este mediodía,

donde encontrarás con el pan al sol la mesa tendida.

Por eso muchacho no partas ahora soñando el regreso,

que el amor es simple, y a las cosas simples las devora el tiempo.)

Take your time here, in the greater light of this midday,

where you find the bread sunned, the table set.

So boy don’t you part now dreaming the return,

for love is that simple,

and time devours the simple things.

In the last recorded performances, the emotion and expressivity is absolute, deliberate, almost a ‘’Cante Jondo’’ from the deep. The famed Chavela Vargas, rumored to have once been the seductress of Frida Kahlo to whom she dedicated a cycle of songs such as La Llorona (The Wailing Woman, the crying maiden).

Decades later, we see Vargas’ ruinous appearance, looking like faded stone, as she sings of loss of simple things and of times devouring of cherished ornaments, confronting the audience in a bold artistic manifestation.

Despite the presence like faded stone, the weight of having lost all ornament, this is by no means minimalist or reductionist — for the emotion is such that many viewers from another cultural context would find it over-the-top and embarrassed to their guts, seeking the exit of the dark theater with their eyes. In Vargas’ performances, there is no timidity, no map of escape escalators, before a song to mortality: a mortality that not only devours youth and the body, but also eats away at love despite pledges of deathlessness.

Looking at Vargas’ performance, or at Francisco de Zurbarán’s paintings, undoes all ‘’protestant’’ sober aesthetic criticisms favoured by cultural theorists. Even the noble recently dead Tony Judt and Susan Sontag, who had appraised restraint and a Spartan reduction of extravagance as signs of aesthetic and moral sincerity, would be left dumbfounded by such expressivity unfathomable to them. Such thinkers baffle Latin America, and are rightly baffled by it. Moralistic minimalism and the modern morality play in art at best justify the monstrosities of Andy Warhol’s Campbell cans in art and the conservative restraint of Carver and his thousands of MFA-trained imitators in contemporary literature. The ‘’cante jondo’’ or ‘’deep song’’ erodes all their dulled varnish, laying bare the underlying chaos.

Intro by Chana Bloch on her and Ariel Bloch’s co-translation of the Hebrew Song of Songs

Chavela Vargas (originally Isabel Vargas Lizana) was born in Costa Rica, but garnered renown as a Mexican artist through her long career in Mexico “ Mexicans can be born wherever they want to be born’’ she said when asked about her Costa Rican upbringing.

Many poets who left their countries of origin for Mexico have later on defined themselves as Mexican, such as Roberto Bolaño who insisted he would always be ‘’a poet from the DF’’ of the Mexican capital.

Vargas breathed her last, hospitalized in Cuernavaca Mexico in 2012. Perhaps we are really from the places we choose to die in — although we do not choose to die, at least more than fate exerts an affective role in what determines the mise en scene.

The song Simples Cosas performed by Vargas runs counter to ‘‘Western-Buddhism’’ and other notions of a desire-less living unattached to the things of life that will deteriorate or are breakable. The song speaks of pain at sudden deterioration, earthly love and not the disembodied, purely spiritual love. A tearjerker of a ballad, it advocates for life in all its poetry of pain. Vargas was a hardcore alcoholic who stopped drinking near the end of her life. There are enough advocates for death, the competition fierce for new advocates accessing the emerging market. But everybody knows the best books and music make you want to live.

A paradox resides in being the artist who can only temporarily postpone the death-wish: during the act of creation or good writing, one must excavate for justifying the desire for life, to advocate for humankind. To make art, the doubter of any motivations for this life must then at least temporarily, during the act of creation, self-convince, suspend disbelief, in order to then be able to convince the audience and suspend their disbelief. (Perhaps what part the audience calls life actually resembles the hospice. In that case, their belief in dead things, their placid necrophilia, must be challenged, mangled by the performance.)

There were artists of gloom like Argentina’s Alejandra Pizarnik, who navigated ever-so-narrowly the edge of an un-sublimated, raw misery and the frankness of depression, using her glooms as materials, yet not the prime materials. Just in the nick, Pizarnik narrowly succeeded at lessening misery by art.

Perhaps a more extreme example of a poet fond of life would be the pedestrian ex-shoeshine boy Armando Tejada, who according to rumour exclaimed at a banquet in Mendoza ‘’the taste wine is green, I tell you! Damned it I said the colour of the taste, not the colour of the wine. A flavour can have a distinct colour. Where the hell is Breton? Bring over André Breton, he’ll tell you better. Did you say Breton invented surrealism? He didn’t invent it. The people invented surrealism! The wine tastes green!’’

On the author of the song “Las Simples Cosas,” popular poet Armando Gomez Tejada: A Micro-biography.

The lyrics of the song are by the Argentine poet Armando Gomez Tejada, an anarchist poet and songwriter from Mendoza, much of whose work was influenced by a childhood spent as a shoeshine boy and street-child. This is of course among Tejada’s simplest songs, yet still gives a valuable punch to the idiotic face of Carlitos Gardel, the tango-singer who lied to us all by singing of returns to unchanged barrios and that “20 years ain’t nothing.”

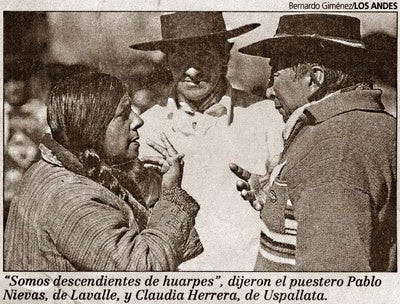

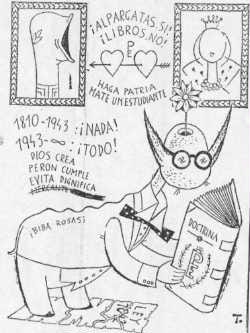

Tejada was born in 1929 as the before-last offspring of 22 siblings. Orphaned by his father, a goatherd, a few years later. His mother sent him to the countryside, to be raised by his aunt Fidela, who conserved indigenous traditions of the Huarpe people. When his first book Pachamama, dedicated to his mother, won a regional prize in Mendoza, poetry critics who had never heard of him speculated the unknown youth by the name of Tejada was a ruse and did not exist (“fake news” in today’s jingoism). The Pachamama poems, he claimed, were influenced by the cosmology of the Huarpe, his aunt’s people, and are poems about human solidarity. Tejada, like certain other anarchist-fight-spirited songwriters, were sticklers for anti-demagoguery despite their populism, and Tejada came into conflict with Juan Domingo Perón’s presidential democratically elected rule, in spite of a later, avowed appreciation for the first lady and politician Eva Perón, who represented the tenderer,more social-democratic face of Peronism.

Radio dropped Tejada in the hope of siding with political prominence, until the right-wing coup, general Aramburu’s “Christian revolution’’ that exiled Peron and the peronists. Many on the radical left had strangely supported the fanatical Catholic military coup, that would either reward the left-collaborators or banish them anyway. Tejada swam back onto the airwave.

The poet’s texts were adapted by Mercedes Sosa for her earlier, faster-paced, more exciting albums — these sound more raucous, swingy, and free from the solemnity that beset Sosa in her late stardom.

“Andar, Andar, sangre y sol, sueño y sol, Wandering, Wandering, blood and sunlight, sun and dream’’ she sings.

Despite the undeniable melancholy of Argentinian culture — from its pretentious capital centre, up and down to the humbler Northernmost and Southernmost provinces — Argentina is by no means as exceptional an oddity as many Argentineans believe. Dominican Bachata ballads come to mind, though lacking the poetic and ideological depth of tangos. The narrative ballads of the Colombian Vallenato became an intesne subject of study for none other than “Gabo” Gabriel García Marquez, who said:

“Without any doubt, I think that my influences, especially from Colombia, were extra-literary — More than any book, I think what opened my eyes was music, Vallenato songs… What called my attention most of all was the form the songs used, the way they told a fact, a story… All quite naturally.” (source)

García Marquez championed that valley-music singing of the shoot-out-riddled region of Colombia’s mountainous Caribbean coast. Being an informal ministry of culture in his country after the Nobel prize, his defenses of his taste led to its consecration by UNESCO.

Vallenatos are often jokingly referred to as “background music for suicide” as are the tangos of the Argentinean centre and the sad “zambas’’ (not to be confused with Brazilian fast-paced sambas) and chacareras of the Argentinean arid North. This is why upon entering any cheap bar I shall always make a beeline to the jukebox with a coin to cut open the machine-neck pouring Vallenato.

Notes on a Journey to the Ever-Dying Lands: A Devouring was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.