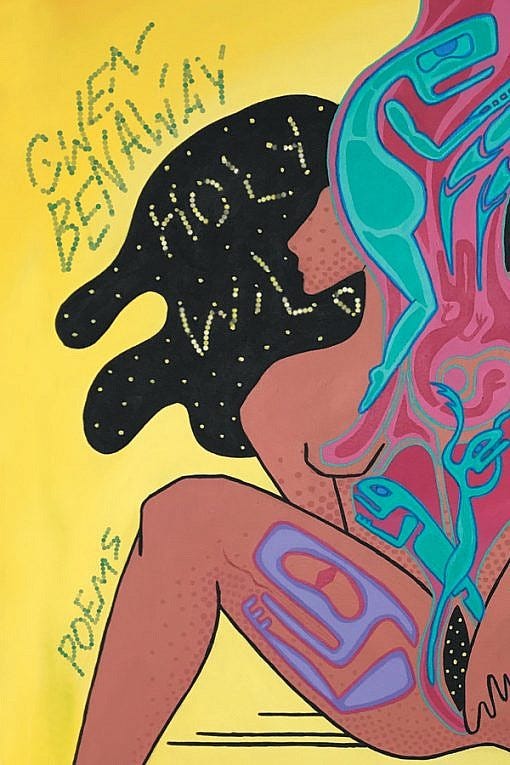

Desiring recognition is only human, but the most vulnerable are also the most likely to get recognition at the highest cost. Especially when this recognition is emphasized at the expense of letting aside any kind of critique that challenges the structures that allow and promote the violent erasure of the most vulnerable in the first place. In her latest collection, Holy Wild (prefaced by the Anishinaabe visual artist Quill Violet Christie-Peters), Gwen Benaway demands such critical recognition as she finds the strength to talk about girls like her, Indigenous and transitioning in a world selling love on street corners, but only to the ones willing to confess and perform their resilience the way they are expected to.

Making use of Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe) words and phrases as a second-language learner, Benaway traces the history of Indigenous transness and links it to the gender diversity inheritance coming from ancestors who “married for a season or two / with multiple lovers in every hunting ground” and saw trans people not as “a white disease” but as holy. Still, her poetry does more than simply honoring her ancestors and their understanding of Indigenous transness — it also speaks back to them, trying to complicate the discussion about notions that are quick to shun or even wipe out Indigenous transness that doesn't conform to more traditional grasps.

Tackling disastrous heterosexuality by attempting to pass and recover her femininity against male bodies while trying to get space for her own body caught on “the middle ground of gender” determines Benaway to acknowledge that “we do anything we need to /even if we have to/kill ourselves first.” It’s also when language reveals its own limitations, dictated as they are by white cis-heteropatriarchy. A new language should be created instead, one that could at least point in the direction in which so few straight, cis, white people are willing to go, the kind of language that doesn't rely on vicious exclusions such as visibility/desirability vs. disposability, making Benaway comfortable enough to affirm: “what I mean is a transition is as simple as pulling bark / from a tree without stripping / what keeps it alive.”

I don’t hang with boys anymore. they want one thing but I’m many.

I text my friend “am I straight now?” she says “obvsly.”

the obvious thing about heterosexuality is no one is happy inside it.

the boys who fuck me are the only boys brave enough

to embrace the soft and hard of themselves.

(…)

I’ve only been a girl for a year but I’m already bruised by boys.

being a straight girl is living inside a violence you can’t name.

I delete my online dating. I take a vow of celibacy.

what I want from boys is not queer or straight, feminine or masculine,

but fearlessness embracing honesty, kindness giving space.

what I desire is who I am free with.

The history of the Indigenous body is mostly absent from colonial imagination, and gender is only one of the tools used to erase this body and its nonconformity. Common language is also denied in the process of whitewashing this history, and visibility has to be made up from scraps, from words that allow one to unlearn compulsory socialization patterns or, at least, let a trans woman imagine how a world would look like if only her body wasn't “a burial ground /of what they left behind.” Discarding masculinity without quite knowing how to replace it or with what, refusing to let go of desire that cannot find its expression in sanctioned forms, celebrating fear, confusion and shame — these are all standing up for the (im)possibility of Indigenous transness that looks for ways of being within the current settler society while cracking the present tense and imagining itself in the future.

I wish I could be pretty enough to matter.

even if hormones dissolve me

when surgery breaks me

I’ll still be this girl, smart as a storm

sharp as a silver knife

strong as a sermon

as ugly as

she is honest.

(…)

trans girls don’t get answers,

just questions

from people who can’t imagine

us as worthy of desire,

questions to remind us we’re

not the kind of girls

boys want to

love.

But accommodating other people’s desires and expectations can easily hold a trans body captive, objectifying it and denying its vibrancy — it might be easier to perform transness than actually embody it and demand to be seen as implicitly valid. With Holy Wild, Benaway pursues something more than mere visibility or survival in a world bent on destruction where “anthropology is another word / for rape” and violence passes as love. Unapologetically, she dares to imagine and celebrate Indigenous transness as radical softness free of settler projections, as sexually active resistance that doesn't entail oppression, but an urgent desire to be here, right now, despite a reality that refuses to acknowledge or even allow its existence in the first place.

let me repeat this to you because no one else will.

you are beautiful.

you are passable.

you are desirable.

you are real.

you are a miracle and a gift.

***

Gwen Benaway is of Anishinaabe and Métis descent. A Two-Spirited Trans poet, she has published two collections of poetry, Ceremonies for the Dead and Passage with the fourth one, Aperture, forthcoming from Book*hug in Spring 2020. Her work has also been featured in national publications and anthologies, including The Globe and Mail, Maclean’s Magazine, CBC Arts, and many others.

Dissonance(s): Gwen Benaway’s Holy Wild was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.