“The striking originality of this novel starts with the sub-title. What to make of the declaration (warning?) that this is an “anti-travel novel”?

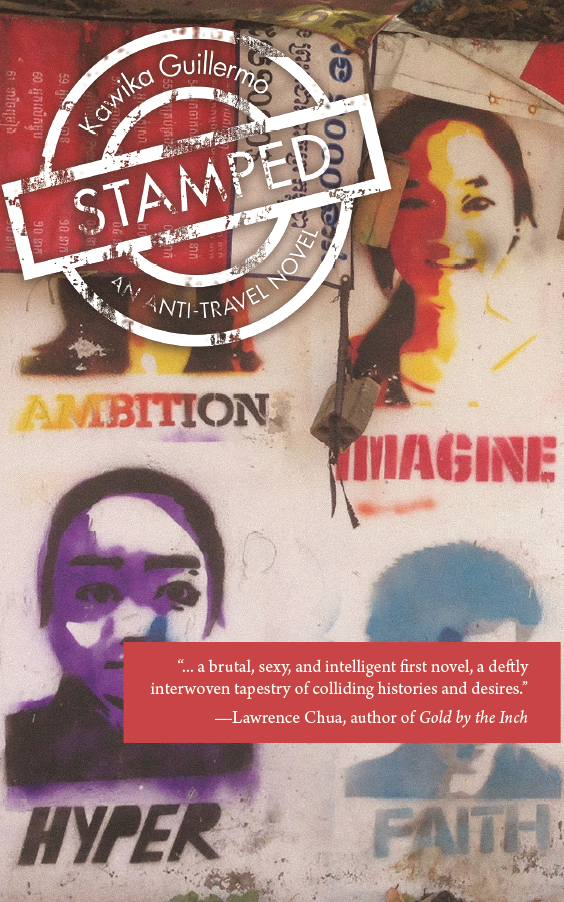

— Bookish review of Stamped: an anti-travel novel

The first two reviews of my debut novel, Stamped, have rolled in this month, and so far both reviewers have found the novel’s “anti-travel” genre its most intriguing aspect. Thomas Dai at Entropy Magazine claimed that “anti-travel” entices readers to see Stamped as a “book which wants to dispel every sweet, uncritical thought you ever had about traveling.” John Grant Ross at Bookish.Asia wrote that “you’ll likely turn the last page of [Stamped] without an increased desire to visit any of those places, or to hit the road at all.” The reviewer then added that the novel forced him to face his own position as a white expatriate: “I’m an old-fashioned white guy with a weakness for colonial nostalgia, and one prone to daydreaming visions of colonial administration and maverick exploration. I still hold to my childhood conception that travel should involve an element of heroic quest.”

Though it does make me giddy to see that the reader’s expectations of travel could be purged forth by reading my novel, and that some readers will feel unpleasantly forced to confront their own colonial perspectives, the great shame of all this speculation on “anti-travel” is that I only included the word in the novel’s subtitle as an after-thought. The word itself does not appear in the novel, nor in any of my blogs, essays, or academic work on travel. It was two years after first seeking publication for Stamped that my partner, who had watched me crumble apart after years of rejections, convinced me to call Stamped an “anti-travel” novel rather than a “punk-travel” novel or a “novel of the dejected.”

So, since writers are somewhat expected to own the language we use, allow me to take a swing and spend this blog post caught in the gravity of this term. Just what exactly is “anti-travel”? I have the sense that it has something to do with 1) traveling as a queer mixed-race person of color, 2) inheriting self-destructive tendencies that have, in the past, bordered on suicidal, and 3) a mission to decolonize the spaces, histories and my own self-perceptions in any way I can. I hope to spend time reflecting on each of these points.

A warning: I don’t want to give the impression that just because someone identifies as non-white or queer that they will inherently practice a sort of “anti-travel” wherever they go. Stamped is in a way about the tendency for anyone to parrot colonial attitudes when high on the travelesque trappings of whimsy and delight.

Anti as in Against

The first travel book I ever read was Andrew X. Pham’s Catfish and Mandala, a story about a Vietnamese American refugee who, after his sister’s suicide, bicycles through the Pacific Rim and into Vietnam. The next travel book I read was Lawrence Chua’s Gold by the Inch, the story of a gay Malaysian/Thai American who zips through his former homelands searching for erotic sex (the more punishing the better).

So it didn’t occur to me, until I started teaching travel literature at the University of Washington in 2008, that travel fiction was known as the last edifice of white male territory, a floating lighthouse with its bright beam scanning eagerly for the next exotic destination. I realized that until quite recently, people of color had been locked out of travel narratives, so that color only remained with the hyper-colorful natives. Rare was the travel book written by a woman, and even rarer the travel book written by a woman of color.

Travel writing has been a staple of Western colonialism since at least the Grand Tours of the seventeenth century, when young hipster-like Europeans would toss about on the new colonial infrastructure to compare themselves to others they saw as backward, uncivilized, perverse, heathens.

The Grand Tour travelers would eventually become colonial administrators overseeing civilizing projects, just as travelers today are set upon paths of cultural understanding and inclusion to later return to the imperial death star that is North America. The lure to travel plagues CIA and military recruitment fairs on college campuses. Travel gives authority to men who write books on how to pick up Asian women (see Kristina Wong’s fabulous review videos of these works), and also permits a certain form of “grisly expat” racism — you know, the beleaguered travel writer who has been to China and tells you with a sly smirk that all Chinese men are scoundrels and cheats.

But today’s colonial travel is unique in that we are no longer encouraging expansion so much as the eradication of our own minorities. Travel today is a gawking form of self-help merely reminding us that home really is home, and it belongs to us (and only us). My go-to example for this is CG Fewston, a travel writer who attacked the novelist Viet Thanh Nguyen for winning the Pulitzer because he wasn’t “a real American” (Nguyen is a refugee). After I got into a twitter-spat with him, Fewston posted the following:

Fewston deploys his knowledge of Viet Kieus to call refugees non-American, and if you disagree, it’s because you don’t know what a Viet Kieu is (he will educate you). His knowledge of “Vietnam’s Civil War,” as he calls the Vietnam War, completely erases America’s violent role from the war and its long aftermath. His self-appointed “travel writer” position allows him to spew this nonsense while claiming to be “apolitical” (the haven for those whose politics don’t ally with any communities or peoples). His travels give him an enlightened worldview, which others cannot begin to comprehend, trapped as they are in their divisive, racist identities.

Fewston’s rants are not unusual among travelers, and for me they epitomize how travel can make people even more bigoted, especially in the age of Trump, which is another age of shamelessly attacking immigrants and minorities. Narratives of travel as a means of “finding yourself” or getting an “alternative education” so forcefully flattens local cultures into whatever can be consumed, sold, eaten and/or fucked, that the traveler is led to see homogeneity as the best way forward. The blind tourist sees a Cambodia of only Cambodians, a Japan of only Japanese, a Philippines of only Filipinos — never mind that each of these states have overseen violent attacks on minorities and immigrants through genocide, war, or writing them out of their own national family.

Traveling Others

Back in 2008, when I found myself stuck inside a canon of Travel Literature filled to the brim with white male writers, I quietly leaned onto Mark Twain, who wasn’t quite there with me in experience but did belch the best anti-imperial rants. Like this line from his Following the Equator, about how indigenous people in Australia were made barbarous:

“When a white killed an aboriginal, the tribe applied the ancient law, and killed the first white they came across. To the whites this was a monstrous thing.”

Anti-travel, mayhaps, is not about facing the monsters (or “the madness” of Conrad, or “the echo” of E.M. Forster, or “the nothing” of the NeverEnding Story), but about how those monsters are created, and what for. In Twain’s edict, “There are many humorous things in the world; among them, the white man’s notion that he is less savage than the other savages.”

Years after I taught Twain, while living in China, I grew obsessed with finding “my people,” meaning those addicted to travel not because it was educational or fun, but because some despair in the American experience drove them to it, again and again. “My people” were not in travel anthologies, even the kind that included the hyper-masculine yet celebrated writings of Ernest Hemingway, V.S. Naipaul, Italo Calvino, or Amitav Ghosh. These writers never pinched me much. I yearned to consume not the incense or spices of another land, but to smell the author’s own shit, to sniff out whatever guilty pleasures they had hidden within them.

Over the years I reworked my travel literature course to only include those othered, unruly and willful travel writers. One was Jamaica Kincaid, whose A Small Place, about colonial tourism in Antigua, basically said “don’t you ever fucking come here.” Then there was Nella Larsen, whose novel Quicksand basically said “if you’re a minority, you gotta gtfo of America.” Another was Zora Neale Hurston, who traveled as an anthropologist collecting black folklore, zipping through the South in a stylish car, a shotgun always at arm’s length. Two others, Richard Wright and James Baldwin, I imagine traveled to France after listening to that one Jay-Z line on repeat: “If you escaped what I escaped, you’d be in Paris getting fucked up, too.”

Then there were the authors that influenced my own writing the most: R. Zamora Linmark and Lawrence Chua, whose novels take the reader on queer romps through Southeast Asian spaces, eerily aware of the historical baggage within everything around them. Linmark’s Leche is about a Filipino-Hawaiian gay traveler who returns to the Philippines and hates everything there until he is so broken by the place that he realizes there’s a pleasure in the pain of failure, if only he would unclench.

Lawrence Chua’s Gold by the Inch remains my favorite travel book, and nothing epitomizes anti-travel to me more than a scene about halfway through the novel, when the unnamed narrator, after wooing a white expat into a hotel room, dresses him in a rubber suit and then proceeds to pee into his suit and mouth. Chua describes:

“He is surprised, but it only takes a moment before it fades into indignation. You put your hand over his mouth and continue urinating . . . you push him down, still peeing. Cover him with your body. The rubber takes on a new sheen.”

The scene remakes the colonial violence of Malaysian rubber plantations into the pleasures of erotic vengeance. The brown boy leaking gold, inch by inch.

Anti-Travel Definitions (to be disowned)

Perhaps I could leave it there — anti-travel is a brown dude pissing vengefully into a white expat’s rubber suit. As beautiful as this image might be, I can’t leave well enough alone. The question still remains: just what is an anti-travel novel?

At home, race is lived as a dust-layered filter that only lets through the most sanitized ways of being. The limitless plurality of possible selves feels reduced to a few. But when you travel, race turns to strangeness, to the unknown, or as I wrote in the first page of Stamped, “your race card has turned wild.” The constraints of racial otherness remain, yet no longer is one pinned to a set of familiar types.

By anti-travel I don’t mean the travel bloggers praised by The Huffington Post for not “giv[ing] a damn if their makeup is flawless when learning how to surf in Mexico.”

By anti-travel I also don’t mean to give attention to the banality of travel: the document gathering, the Visa runs, the airplane food.

I mean the decolonization of travel literature, which is decolonizing the idea of movement as a means of finding yourself, of becoming more empathetic towards others. Mark Twain once famously described travel as a means of acquiring “broad, wholesome, charitable views of men and things.” Anyone who believes travel in itself makes people wholesome and charitable to others has not met enough travelers.

Anti-travel is anti- in the sense that it is opposed to the self-making, self-generating, self-aggrandizing presumptions that give value to those who are mobile and can afford a plane ticket. I am anti- this in every which way.

Anti-travel is not about self-making but about self-destroying. One does not learn to love oneself but to hate the self that once was — the self that took their privilege for granted, the self that once thought simply, flatly, about everyone outside their own corner. Perhaps this could result in a more “broad, wholesome” view of the world, but it only comes with great loss of the self (and by the self I mean one’s attachments to family, gender, race, community, religion, and nation). Unless the traveler is willing to risk this loss, I don’t know what travel can do except further colonize the mind.

For marginalized peoples of all stripes, travel from one country to another is not transitioning from being an insider to an outsider, but from being an outsider to a different kind of outsider, to realizing that there is not merely one way to be excluded. Loss emerges by being “othered” anew: who am I without comparing myself to straight white cis-gendered men? What could I become when whiteness no longer lurks on every horizon? With travel, we find that the forms of otherness are vast, multitudinous, each with their own gravity (and dangers of crashing). But in this somewhat finicky means of wresting down our own self-worth, we find new ways to orbit what others call freedom.

On Writing the “Anti-Travel” Novel was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.