“gi tinituhon : in the beginning fuʻuna transforms her brother puntanʻs back into tanoʻ : land, chest into langet : sky, eyes into atdao : sun and pulan : moon // then her breath blooms the oddaʻ : soil and achoʻ tasi : coral \\ then she dives into the place [we] will name humåtak bay // then her body calcifies into the stone from which [we] were born \\ laso fu’a : creation point”

– Craig Santos Perez, “organic acts”

“So we slowly begin with what ʻōlelo / we know; E hoʻoulu ana kākou.”

– Brandy Nālani McDougall, “Ka ʻŌlelo”

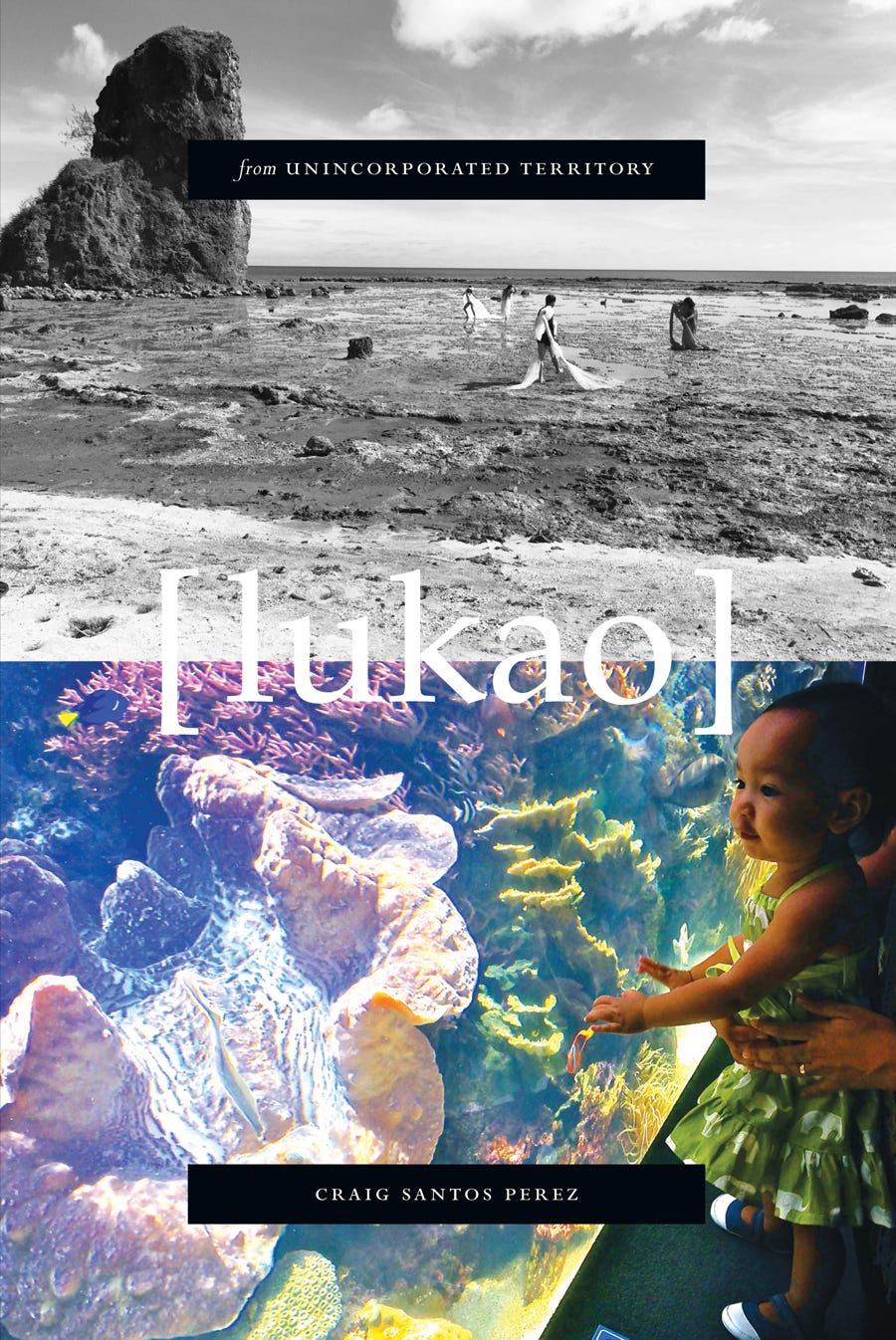

[lukao], the fourth book in the series from unincorporated territory, by Chamorro poet Craig Santos Perez, offers a holistic and ecologically-sound meditation on cultural and linguistic reclamation. Moving between Guahån (Guam), Hawaiʻi, and California, [lukao] considers the Chamorro diaspora, from its origins, to the burdens of colonial conquest, to the birth process of the poet’s daughter, as experienced by Santos Perez and his wife, Native Hawaiian poet Brandy Nālani McDougall, whose presence is felt throughout the collection. Santos Perez navigates the palimpsest layers of communal memory, weaving together ecopoetry, prayer, ritual, food culture, familial birth narratives, and Chamorro language, as well as Hawaiian, into a cycle of resonant poems.

The book offers five sections, four of which spiral through excerpts from longer pieces, and one of which presents a circle of gratitude for communities of birth, of care, and of love. Each of the first four sections also begins with a poemap visually delineating military and colonial damage to Guam, and a fragment of a short epigraph which runs throughout the collection. All five sections end on a poem comprised of repetitions of the hashtag, “#pray for ___________ ” which echos the recurring Chamorro refrain “tayuyute [ham].” The long poems which appear throughout the collection include “the legends of juan malo (a malologue),” “understory,” “organic acts,” “Ka Lāhui o ka Pō Interview,” and “island of no birdsong.”

The collection begins with a “Map of Contents,” and the Chamorro phrase “hånom håga’ hånom,” foregrounding the theme that water is life. The collection signals Pacific Islander and Indigenous ways of knowing with its epigraph from Joy Harjo, “Everyday is a reenactment of the creation story.” The dedication to the author’s wife and daughter explains that references to [you] and to [neni] will indicate references to Brandy Nālani and to Kaikainaliʻi, respectively. Following this, we are presented with a map of undersea communication cables in the Pacific, disproportionately routed through Guam, which is labeled in the map as “~ ~ ~.” From the beginning of the collection, we are presented with ways in which Indigenous and Pacific Islander forms of knowledge and experience interact with colonial forces which threaten to erase and overwrite this inherited knowledge, as well as ways these forms of knowledge present access to resources and community survival. We are also made aware of the relationships between environmental and ecological damage and how these too are directly connected to settler states and economic colonization.

The structure of [lukao] centers Pacific creation narratives and practices of storytelling, as well as the vital importance of water in the region. The collection also resonates with cultural and linguistic resurgence, very much in conversation with Brandy Nālani McDougall’s work with Native Hawaiian forms of cultural revitalization, and her poetry collection, “The Salt-Wind: Ka Makani Paʻakai.” In her collection, McDougall navigates reclaiming ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi — Hawaiian language, and “E hoʻoulu ana kākou,” ways that growth of people through language resembles the growth of plants native to Hawaiʻi. Santos Perez engages with ʻŌlelo as well as Chamorro language, acknowledging his own place in Hawaiʻi as a Pacific Islander, while carefully rebuilding ties to the language of his birthplace and family.

One of the many astonishing features of the collection includes the poet’s navigation of language and the balance between multiple languages spoken by Pacific Islanders, including English. Because many Pacific Islanders have faced linguistic discrimination and colonial policies of outlawing their languages, the languages most widely spoken in the Pacific region are the colonial English and French. In his work, Santos Perez both acknowledges this and allows access points for readers of English who are not Pacific Islanders. Most of the Chamorro words used in the collection are tied to related English words at some point in the collection, so that a reader who doesn’t speak Chamorro is able, through close attention, to have an idea of what they mean or how they might be translated. At the same time, the words are not directly glossed or given asterisk or footnote translations, which would both deprivilege the Chamorro and remove some of the engagement work of the reader with the practice of learning language, which is such a central theme in the collection. The collection is to be commended for providing such a thoughtful balance concerning its linguistic tasks.

To delve further into the long poems in [lukao], the series “the legends of juan malo (a malologue)” offers a history of Guam, beginning with, “Guam was born on March 6, 1521, when Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the womb of Humåtak Bay and delivered [us] into the calloused hands of Modernity. “Guam is Where Western Imperialism in the Pacific Begins!” St. Helena Augusta, tayuyute [ham] : pray for [us].” The use of italics for the English equivalent of tayuyute [ham] flips on its head the English poetry convention of italicizing non-English words.

This series of documentary poems present both Western histories of Guam and counternarratives, through a variety of strategies, including humor and irony. The sections of the poem are subdivided into “the birth of Guam,” “the birth of Guåhan ,” “ the birth of Liberation Day,” and “the birth of SPAM.” This last section reminds us that, “Eight pounds of SPAM die in a Chamorro stomach each year, which is more per capita than any other ethno-intestinal tract in the world. Guam is an acronym for “Give Us American Meat.” Our guttural love of SPAM was born in 1944, when the shiny cans were berthed from aircraft carriers.” Attending to both eco-poetry and food poetry, Santos Perez grapples with the cultural and digestive impact of SPAM and other colonial enterprises which have been introduced into Guam, and ways that Chamorro food culture has adopted and adapted these introduced items.

The poem series “understory” revolves around the birth process of the poet’s daughter, Kaikainaliʻi, referred to as [neni], and the worlds to which she arrives, including her positioning within the Chamorro and Native Hawaiian traditions of her parents, and the navigation she and her parents must undertake in their own everyday reenactment of the creation stories. This series offers multiple poems in each section of the book, reinforcing the ongoing narrative of creation. The poems in this series include meditations on trimesters of pregnancy, firsts of neni’s life, and creation stories of Hawaiʻi and Guam. The poem “(dear fu’una)” speaks to the Chamorro mother figure Fu’una, the narrator says, “what made you leave / your first guma’ : home … forgive me, i lost / our fino’ haya : first / language in transit, ghost words.” The lost language resurfaces in fragments and ties in to Chamorro origin stories. The poem “(first teeth),” ties in to current events, “how do [we] wipe away tear / -gas and blood, provide shelter from snipers, / disarm occupying armies #freepalestine / / / [you] recite the hawaiian alphabet song / to [neni] \\ what lullabies echo inside detention / centers.” The slashes and brackets seem positioned to protect neni from the outside world, as does the mention of the Hawaiian alphabet song. The visual movement generated by the alternating directions of the slashes also serve to remind us of water.

More recent ancestors, in the figure of “grandma” appear to convey Chamorro stories in the poem series “organic acts,” which connects origin stories to family hi/stories and ties to land and water. This section begins with a quote from M. NourbeSe Philip on ties between water and memory, and relates, “in the past, our ancestors pilgrimaged each year to laso fu’a / / they made offerings and asked blessings for simya : seed, hale’ : root, and talaya : net \ \ they stood in circles and chanted rhymed verses back and forth / / [we] call this communal poetic form kåntan chamorrita (which translates as to sing both forwards and backwards).” This section also offers a story told by grandma in which “once a giant guihan : fish began eating the center of our island.” The story related by grandma involves the Virgin Mary, who “came, wove her gapot ulu : hair into a talaya, caught the guihan, and saved [us],” however, further on the narrator relates an older version of the story, in which, “the men formed a blocade with canoes and the women wove their gapot ulu into a net and chanted kantan chamorrita until the beast was lured to the surface and caught \\ [we] saved [us].” The second version appears in grey text, resurfacing from under its colonial adaptation, and carrying with it canoes, fishing nets, and kåntan chamorrita.

Narratives of birth weave together in the series “Ka Lāhui o ka Pō Interview,” which includes stories of giving birth offered as quotes from Helen — the poet’s mother, [you] — the poet’s wife, and stories of witnessing birth, in the form of quotes from [me] — the poet, and Tom — the poet’s father. Also woven in are the history of Chamorro midwives — a text in strike-out font offers, “In 1907, the U.S. Navy medical officers started to regulate, certify, and license Chamorro midwives … The midwives recorded births in a book as a record of deliveries and for tax purposes. Licensed pattera assisted with home births on Guam until 1967, when the last midwife license expired:” The loss of midwives with this cultural knowledge is juxtaposed with a doula, and a downloaded “hypno-birthing app that we listened to. … basically a hippy haole trying to hypnotise you. It drove me crazy.” Connections between generations take up residence in a quote from [you] describing the birthing process, “I was talking to my dad, who passed away when I was eleven. I felt like I was in a different space, here but not here. I kept thinking about people who I had lost, and I felt them around me. I could talk with them. I was also talking to baby. I was asking her to help me and telling her that it was time to come out. I was trying to prepare her.” Here, we witness a concentric circle of creation stories — a woman giving birth, surrounded by ancestors, a lost parent, and [neni] being born.

The micronesian kingfisher, or sihek, forms the center of the series “island of no birdsong.” The poem invites us to “fanhasso : remember studying native birds of guam in school … 44,000 chamorros now live in california \\ 15,000 in washington / / what does not change \\ st gail, tayuyute [ham] : pray for [us].” This poem also carries us through the birth and development process of the bird, including signposts such as, “day one : blind and naked,” and “day five : flight feather tracts visible on wings.” Grandma and her prayers make a return in this section, “fanhasso grandma gave me her rosary at the guam plasan bakton aire : airport / / i clutched at the beads while standing in line at the boarding gate \\ home is an archipelago // of prayer.” This section also includes the sound of the kingfisher transliterated, and a series of prayers in Chamorro and English, “ ““hu hongge i lini’la’ / tataotao ta’lo åmen”” / i believe in the resurgence / of our bodies because / [we] are the seeds / ginen the last hayun lågu / waiting to be rooted / into kantan chamorrita.” Here, the forms of call and response become a field into which resurgence can be planted, tying the kingfisher’s song into agri/cultural forms of re/birth. Language serves as medium and as a call to renew a culture and to spiral into creation stories.

In [lukao], Craig Santos Perez gathers the scattered seeds of Chamorro language and the Chamorro diaspora, relocating them within Pacific and Indigenous cycles of history and storytelling. [lukao] roots itself in narratives of birth, ancestral and familial knowledge, cultural practices, eco-poetics, and food poetry. It asks “fanhasso : remember,” and “tayuyute [ham] : pray for [us],” always with the knowledge that in the story of the “giant guihan : fish,” the resolution was that “[we] saved [us],” — that Chamorro people used their cultural knowledge of canoes, nets, and kåntan chamorrita to save themselves. This collection performs a multilayered poetics of cultural and linguistic renewal to enact the replanting of seeds and poetic forms of rebirth.

laso fu’a : creation point — Cycles of Creation and Rebirth in [lukao] was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.