Oh, Aries.

It’s finally Spring. This is where the zodiac begins: with the green points of bulbs pushing up out of cold earth, with the trees bursting into flower like so much popcorn, with the sun blazing a little longer and hotter every day.

It’s the year’s beginning, because up until now you were only biding your time until you could start to live again, and Aries knows it. Aries is the baby of the zodiac, and like a newborn, Aries greets the world with a dreadful yawp, dreadful in all the senses, a conquering and thunderous wail of watch out world, here I come and you’d better get out the way or be prepared to have your toes crushed and oh, by the way, I’M HUNGRY.

When I was a teenager, I had my first Aries friend. She used to breathe flames out into the hall of our school (okay, it was Aqua Net and a lighter, but who would think of that? Not me. Aries, that’s who.) She used to yell, “I HATE THAT!” whenever she hated something, which was a lot.

It wasn’t a bitter or a resentful yell; more of a joyful declaration of THIS IS ME. THIS IS ME AND I MAKE NO BONES. I secretly admired her frankness but wasn’t sure how to handle this at first, because I am a Libra and we are famously mealymouthed sycophants who tell people what they want to hear until we actually believe it, and who do not believe in being jarringly emphatic, especially in the negative. Libras are always trying to fit in and be acceptable to everyone. The Libra is busy assembling tasteful pastels while the Aries has pulled on a tangerine sweatshirt that clashes with its purple and navy running shorts and bounced out to the field. The Aries has not even brushed its hair. Strangely, all this unkempt allows you to see how beautiful the Aries actually is.

Other such declarations from Aries I have known: “I have the hugest zit!” “Every time I sleep with him he gives me scabies!” “Look at my diseased penis!” “When I get drunk there is always another taco!” “OMG my B.O. smells like an onion!” “I wasn’t sure what to do, so I stole it!” and “When I’m sixteen, I want to get pregnant and have a baby!” (This last, from a ten-year-old Aries whose parents are probably already stockpiling the Plan B.)

Aries is the original no filter; it’s not that they are trying to shock or offend you; they just don’t see the point of beating around the bush. It’s not that Aries doesn’t appreciate subtlety or sugarcoating (okay, it is, but the evolved Aries recognizes the usefulness of these things even if they themselves can’t be arsed to do them); it’s just that Aries doesn’t have time for it. There are truths to be told. Aries gives us the gift of ingenuous frankness, and we should have the sense to be grateful. Which is not to say Aries is a stranger to theatricality. Far from it. Lady Gaga is an Aries, y’all. Think of her wearing that meat dress and screaming “Born This Way.” That is the way of the Ram. Think of Vincent Van Gogh mysteriously losing his ear and refusing to talk about it, but painting ever more intense works of genius before a slow death by shotgun. This is Aries. Aries doesn’t need things to be pretty. Aries is called to blaze, comet-like, and if what’s left at the end is scorched earth and a crater, well, it was probably worth it.

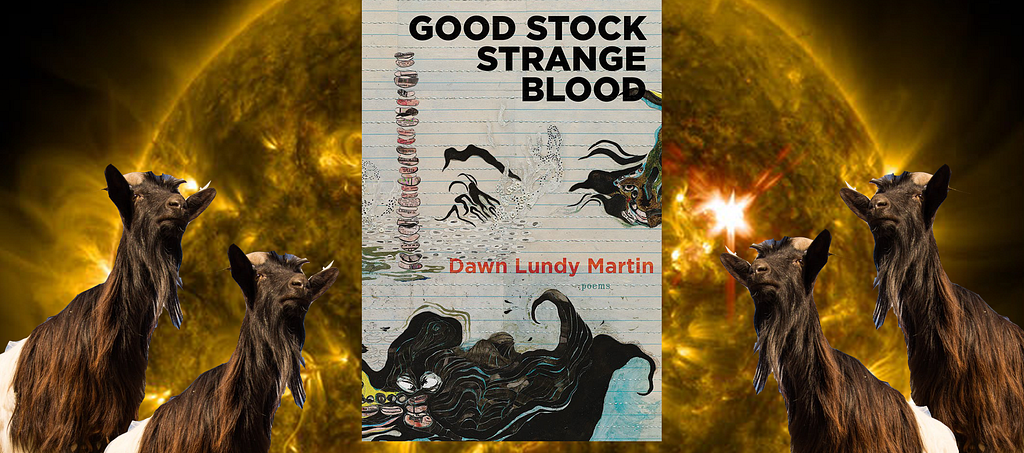

Dawn Lundy Martin’s Good Stock Strange Blood lives in the space of that blistering frankness, that pitiless and eloquent calling of spades. It also weaves a delicious and starry diadem of silken phrase around the following conundrums: “the black embodied body,” the mother, ancestry, race, exploitation, injustice, inheritance, individuality, exploitation, girlhood, violence, legitimacy, freedom — just, you know, a few of our world’s little problems, but they are all of a piece in Dawn Lundy Martin’s work, which is, like Aries, exhausting and brilliant and indomitable and not at all inclined to solve these problems for you. This book is lyrically and visually driven, imagistic, puffs of flash and fire, blood and bone, an entirely different project from the sotto voce universality that often couches this topic. Good Stock Strange Blood is both personal and historical, both intimate and universal, singing the internal song of the soaring and crushing predicament of “How to live between Mother and time?” Its linguistic register is elevated, elemental, unapologetically grand. Its I is a whip and a pillar. Its you contains multitudes and its us even more so.

Some of the poems in this book, we are told, appeared in another form in a Yam Collective libretto, and indeed we can hear many of these words sung, embodied, danced across stages: “Instrumental fissure, instrumental fish, whose rasp / a whip, a book, a story left in the dark body…” The voices seems to interweave and overlap, “a narrative / wired in cells, desolate root,” and despite protests of having centered in the book the question “why doesn’t one just die?” we can hear in and behind the text a hundred other questions:

“What is wholeness if we were never whole?”

“What’s a condition and what’s a duration.”

“‘What is more frightening than a black face / confronting your gaze from the display case?’”

“What exists in the deep ways / of broken things?”

All of these interrogations seem to inhabit the condition called blackness and the trauma that has been inflicted and imposed upon it, both in the visceral immediate of suffering: “to be spilled / to topple / to be toppled / to strain / be stained / strangled” and, with deft exactitude, in the offhand encapsulation of complicity as a moral problem: “Symptomatic of being a slave / is to forget you’re a slave…”

Martin writes about loss as well, the loss of self, of history, of a people, of language: “What language my grandmother spoke, I cannot tell you” and “we’re lost / and our flesh is on fire.” By turns matter-of-fact and alliterative, sometimes lovely but never prettified “shining like a fucking flaccid ninja,” Martin shoots holes in the pretenses we have been hanging around race: “what is the difference between ash and coal, / between dark and darkened, between love / and addiction…” and at the same time refuses to adopt the role of auto-ethnographer, refuses to efface the lived experience in order to adopt a universality, refuses to claim anything other than her own immense and searing thoughts, for as much as the we and you gallop through this work, there is a first person singular that declines to disappear, that pilots us through the mess of an assailed and yet beautiful existence with implacable dignity: “Me driving steadily / the road almost on fire / with no eyes” — bouncing from vignette to dirge to sea chanty with absolute grace, for Martin’s voice has range and is too thirsty not to use it. And as the artist’s apparently pained strokes resolve into a glory of stars, so Good Stock Strange Blood, containing all the contradictions and constraints of the colonized, inhabiting the tension that is, as Dawn Lundy Martin remarks, “forever unrecognized in that relaxed [white] body,” that “tightrope from which we emerge,” bloom as organically into dazzlement: “We will say, how beautiful / our emergence in flame!”

Happy Birthday, Aries. Please don’t ever shut up. You don’t owe us pretty; your gorgeousness thrills through us like a burn.

Real Chaos Astrology Book Reviews, Vol. 4: How the World Blisters You was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.