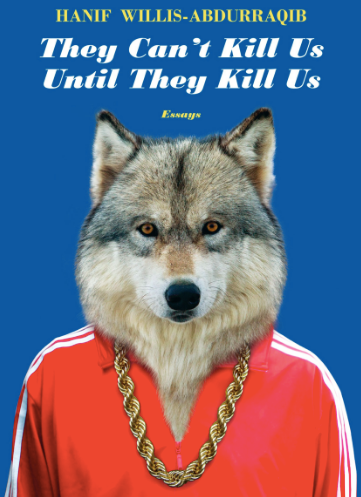

Review and Reflections Upon Hanif Abdurraqib’s They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us

I am intense, maybe. Sometimes, I can be. I like intensity, but not always when it hits too close to home. Sometimes, I need to step away. I needed to step away recently. I did. I found another intensity to settle into for a respite but the echoes came. I couldn’t escape the echoes so I returned. I had to both for duty’s sake and interest.

If you think Hanif Abdurraqib’s collection of essays is just a book about music, you are mistaken. It is intense and it is not a quick read. Not for somebody who knows the sounds and the echoes that don’t always go away. Brooklyn is not Ohio but there are sounds we both know. Oklahoma is not Ohio nor is it Brooklyn but there are sensations that we have all sensed. Sentiments that we might want to get past but the past won’t let us. When I took a step away from They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, I stepped into Shadow and Act by Ralph Ellison. I left one look at how music can affect a person, a black person, and began peering into another view from another black person. Shadow and Act is about more than just music. It is more than jazz and They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us goes beyond hip-hop, pop, emo, and country and gets down to the sounds and echoes heard that are seemingly endlessly heard in black ears from Oklahoma to Brooklyn to Ohio. To not Cleveland, Ohio.

Ralph Ellison proposes that, “…we view the whole of American life as a drama acted out upon the body of a Negro giant, who, lying trussed up like Gulliver, forms the stage and the scene upon which and within the action unfolds.” Ellison goes on to write about how the Negro body was exploited. Hanif and I on the other hand, decades removed from Ellison, can certainly understand that sentiment. And, see how black bodies are still being exploited. But we are also forced to look at how we (can) exploit ourselves. Black folks can be both the stage and the performer upon that same stage.

This collection is a collection of echoes. It is reflections and refractions, soundwaves and visions that keep coming back, sometimes sweetly and sometimes intensely. Abdurraqib can make a lyric a trigger. He can take the song and return us to another scene where we are back to being the scene where we have been since day one on this continent. We are exploited and expendable but this time maybe only if we allow ourselves to be.

The first essay starts out, “This more than anything, is about everything and everyone that didn’t get swallowed up by the vicious and yawning maw of 2016, and all that it consumed upon its violent and rattling which echoed into the year after it and will surely echo into the year after that one. This more than anything, is about how there is sometimes only one clear and clean surface on which to dance, and sometimes it fits only you and no one else. This is about hope…” Right here, at the start, from the get-go, the jump, we are taken to church with Chance the Rapper. I should state a hesitancy to use “we,” but reading this book has me feeling like I am in the choir and the congregation, the audience and sometimes even on the stage but mostly, even in the songs I don’t know, I feel close. I understand. This book wants you the reader to get it. You read these essays and you want to testify. You need to clap. You have sadness at times but also hope. And, hope can be hard to come by at times, specifically, the kind of hope that lasts.

“It’s easy to sell people on optimism, but it’s hard to keep them sold on it, especially in a cynical year.” Sell it and be sold on it. What isn’t for sale? What isn’t an asset of some sort in a land built on exploitation? “I think, though, that a natural reaction to black people being murdered on camera is the notion that living black joy becomes a commodity — something that everyone feels like they should be able to consume as a type of relief point.” Throughout the book and through the variety of shows, places, performers, years, Abdurraqib both allows himself to enjoy music within a white setting by white artists as well as allowing room for white folks to enjoy black music made for black folks. Perhaps, there’s an exchange of joys even though those joys come from different places and might be of unequal values. What’s important is joy itself.

One of the most tender scenes in the book (other than that ending which is half a heartbeat and half a teardrop melded together) is in “Surviving On Small Joys.” This essay speaks a bit to gender and sexuality which of course gets me all emotional but is absolutely essential to any major discussion on community and coming of age. Hanif is looking down at a parking lot where boys are playing.

“Falling, laughing, and getting right back up. This small bit of joy, for no reason other than because it is summertime and they’re with their friends and they’re outside and free. I do not know what they knew of death, or if they knew that a world outside of their own free world was mourning.”

Unfortunately, as we move further through the book we get to growing up, and we lose a little joy. Other joys are available, certainly, but that innocence is gone as we begin to understand our place in the world, where we live and who we are as we exist there.

Brooklyn is not Ohio and my corner of Flatbush and Church is not “…the corner of Ohio that [Hanif is] spending Thanksgiving …” But, what comes next, I understand. I know. I lived.

“…though of vastly different demographics, [one] can tell the difference between a gunshot and fireworks. This knowledge is essential if you’re black and a child…perhaps dreaming of the outside world and all of its possibilities. The key is in the echo…”

Go into this book with dreams and hope. Enjoy the dreams and hopes that the author shares with you. Hear the music of Chance, Cash, Migos, Springsteen, etc. Sway and swear as you read this remarkable undertaking but beware of the sadness that exists even as joy persists. Walk away if you need to but come back. It’s worth it. The echoes in this case can be both the sorrow and serenity of getting lost in a song but what is really happening is that for some brief moments, there is an understanding. A knowledge that is built from years of sentiments echoing back endlessly while still allowing for some hope.

It Ain’t About How You Go Out It’s About Going Back In was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.