‘No se puede ser dos cosas. No se puede ser pintor y escritor. Aunque la pintura me ayudó a escribir y la literatura me ayudó a pintar.’ [One cannot be two things. One cannot paint and write. Although painting helped me write and literature helped me paint.]

What is the value of a statement like this? A dubious assertion followed by an admission of ambiguity. Clearly the first statement does not have to be true—there have been many simultaneous painter-writers, focusing on one art more heavily than the other, perhaps, but practicing both all the same. What does come through clearly is the personality of the person who spoke these words, the Chilean artist and novelist Adolfo Couve (1940–1998). Couve’s self-doubt, his admission of the contaminating influences of artistic practices, and his attempts to define art and reality are all on display.

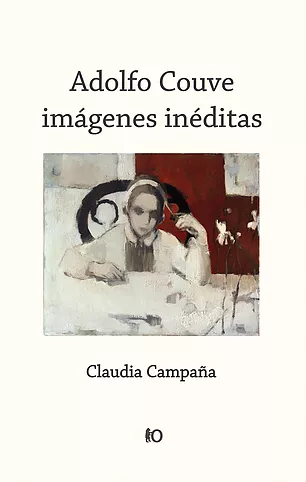

In Imágenes inéditas (Orjikh, Santiago, 2017), Claudia Campaña, an art historian at the Pontificia Universidad Católica, examines a collection of newly discovered images by Couve. A chance find leads her to put aside other work to examine the early sketches of Couve, on whom she has written other books and several articles. What exactly is under investigation? A number of minor drawings that would have little importance were it not for what they prefigured, as well as a couple of fascinatingly enigmatic paintings.

The pencil sketches demonstrate the young artist putting himself through his paces, attempting to discover the fluidity of line that captures an essence, or the relationship between the sharp line and soft curve. There are many images of nude women, which Campaña, both in her descriptions and in visual side-by-sides, holds up next to the great works. It is a generous comparison, but the spontaneous pencil sketches of Couve’s drawings suffer from the contrast with the fully worked-out achievements of Manet’s Olympia and Goya’s Maja.

One does see Couve settling into his eventual style, however, in all its murkiness, anxiety and muted beauty — a style he would eventually give up, at least in the form of painting. Why? The dilemma of the choice between art and literature, which many have happily evaded — content to practice both, even if one takes precedence — was for Couve a source of angst. A choice had to be made, and he chose to write.

Campaña, primarily interested in the visual arts, laments this loss, but she also presents her ambivalences about Couve’s personality. In the middle section of the book, following the discovery of the 1964 painting Melliza, Campaña segues into the story of her odd, profound and unsettling relationship with Couve, which ranges from her bringing a Pan de Pascua as an end-of-term gift to his apartment, to him making a pass at her before asking if she has ever suffered, to her telling him about her blind sister, to him requesting that she be his classroom assistant, to her gaining his intellectual respect and eventually taking over his position as Professor of the History of Art at the Católica.

In structuring her book in this way, Campaña seems to have adopted the tactic, conscious or not, of tucking the most autobiographical, ‘juicy’ bits of narrative into the middle, as if they were a jewel suddenly chanced upon, or the cheesecake filling of a chocolate bundt cake. (I am reminded here of Manuel Vicuña’s skewering chapter on contemporary police corruption in the middle of his study of detective fiction, Reconstitución de escena.)

Campaña closes this anecdote and continues to trace the trajectory of the artist from 1959 to 1964 to 1967 to 1987, when he finally makes his ‘turn’ toward literature. Couve’s final works — a portrait of a girl at a table, possibly reading or playing with her hair, as well as a portrait of a young woman reading and a series of works on the circus—all come under the analytical lens. These images seem a far cry from the early pencil drawings of women, but some essence in the people suggests a similarity. Campaña pinpoints what it is: they are all solitary figures.

Solitude is also a preoccupation in the strange, fractured literary work of Couve. All of his novels, he admitted, were to some extent autobiographical, workings toward a self-portrait. Perhaps this is why Campaña’s comment about her blind sister so impressed him: what more sobering image can one imagine of being alone in one’s reality?

‘Descriptive realism’ is the way that critics have described Couve’s work, a term that immediately relegates the writer to a certain ghetto in literary history. Couve, in contrast, referred to several of his own works as ‘comedies’. If so, they are dark ones, but their fragmented individual images are strange and compelling. Imágenes inéditas, which itself reads like a work of pieced-together fragments, offers a sensitive new perspective on the many dualisms and fascinations of this Chilean artist.

Painting Lessons was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.