“The years form a mythology I can almost explain. / I see in colors because they are always so much // A part of the problem:” — Charif Shanahan, “Self-Portrait in Black and White”

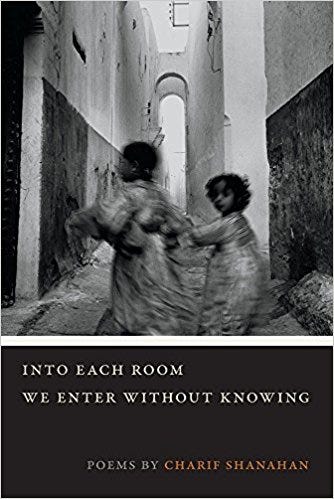

Visceral colors, landscapes, and bodies flesh out the poems in this breathtaking first collection by Charif Shanahan, which unflinchingly delineates the joys and pains of queer identity and the inhabiting of liminal spaces between Black and White, across continents, and within English, French, and Arabic. The poems in this collection range from history to lyric to philosophy. They draw from influences of paintings by Jean-Léon Gérôme and poetry by Plath and Darwish, and they converse with the work of Solmaz Sharif and Safia Elhillo. They extend their reach from New York to Zurich, from Italy to North Africa.

The collection is divided into four sections, each of which moves organically through its own range of spaces and themes. The poems make allusions and references to work by Sylvia Plath, Mahmoud Darwish, and contemporary poets including Danez Smith, Fatimah Asghar, and Safia Elhillo.

Bookending the collection, we find poems on the boundaries between life and death. The poem “Whiteness On Her Deathbed” reveals the speaker preparing his mother’s body for a ritual of sending off.

“I remove each ring and, speaking,

To myself, if not to her,

Slide my fingers through the hair

She had worked

To keep straight, a damp heaviness

I palm, and begin

To braid each curling tress,

Tying her

Back to herself —

Turning her face

I scrub the back of the neck,

A field of serpents, reaching

Into the braids”

The speaker lingers in a last conversation with his mother, attending to her body for the final time. As his mother’s ties to her body and the physical world unravel, the speaker braids each curl, tying up the ends of tresses whose roots he names serpents. In the process, he binds himself to his mother, to her complicated histories and the unexpected ways in which her life has been woven together.

The poem “Your Foot, Your Root,” with its reference to Plath’s “Daddy,” explores further the concept of familial ties and the passing down of family traditions. One section of the poem takes the form of an exercise in logic, taking quotes from philosophers, poets, and family members to explore spaces between America, Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa.

“Heidegger says Man acts as though he were the shaper and master

Of language, while in fact language remains the master of man.

My mother says I am not African American, I am an Arab.

My friend Solmaz writes It matters what you call a thing.

Heidegger says Language is the house of the truth of Being.

Majd says Here they think I am a Dominican. I do not understand.

Omi says Hada sweena, hada khiba.

Therefore: The master of man is the house of the truth of being.”

Shanahan points out the vital importance of naming, in reference to poet Solmaz Sharif’s collection Look, on the impact of American military violence and aggression on Iraq, Iran, and the Iraqi and Iranian diaspora. We see the words of philosopher Martin Heidegger interwoven with words from the speaker’s mother, and grandmother, referred to with the traditional title Omi, and a friend who faces mislabeling by American contemporaries.

The speaker’s mother points to the convention of North African, Arabic and French speaking Black people to refer to themselves as Arab. The speaker’s grandmother, as we see earlier in the collection, is referencing two African American women, Brandy and Monica, in the video, “The Boy Is Mine.” Monica, wearing her hair straight, Omi refers to as sweena, beautiful, and she refers to Brandy, wearing her hair in braids, as khiba, ugly. We see language shaping and being shaped by identity, interacting with and defining embodiment and the state of being. The speaker points to the use and embodiment of Arabic as an identity marker for his mother and grandmother.

Arabic as a form of self-definition recurs throughout the collection, appearing prominently in the poem “Asmar.” This poem calls back to the work of poet Safia Elhillo, who explores the role of Arabic language in her identity as part of the Sudanese diaspora. Referencing poems by Elhillo which deal extensively with the word asmar, this poem picks up the theme in relation to the speaker’s family.

“Dear S —

They told me again today that I was not Black:”

“Our mothers tell us we are not like them: Les Africains sont là-bas!

Our mothers defend what oppresses them.

Often I ask But if I am American and my mother, wherever she’s from, is Black,

Does that not make me — Always I stop, knowing both answers.”

“In our homes

We say asmar asmar — a chant of shame they cannot hear —

As the body changed with the earth and to contain it we must name it —

Asmar meaning dark,

Meaning Black,”

The speaker’s mother and grandmother define themselves as Arab, rather than African. They try to explain that Africans are on the lowest level of the social hierarchy, and that their own traditions are more closely tied to Arabic speaking culture in North Africa. The speaker’s omission of the words African American serves to emphasize the erasure of his own identity. In reclaiming concepts of asmar, dark, Black, and African, the speaker must navigate spaces his mother and grandmother have been conditioned to avoid.

The poems in this collection tie concepts of identity and naming into the material world and natural phenomena. In the poem “The Most Opaque Sands Make for the Clearest Glass,” the speaker considers his own and his mother’s African and Black ties while speaking to his mother about her identity and the ways she wishes to pass her traditions on to him.

“The dark matter

Turned its face to mine”

“ how

Can she sit there and say, Child

I am not, we are not —

In spite of — no, inside of

The dark fact of her body?”

The title of the poem references the process of glass making, in which grains of sand, opaque in their original state, become transparent in their transformation to window glass. The physicality of this transformation becomes a background against which the speaker considers the refusal of his mother to identify as Black. His mother’s insistence on identifying as Arab complicates the speaker’s already challenging navigation of his identity.

The speaker’s identity also comes into question from fellow Americans. The poem “Persona Non Grata”

reveals tensions faced by the speaker in an African American context. Here disembodied voices address the speaker, challenging the speaker to define and support his own identity.

“You spoke Not like us. You spoke

Cracker, please. With skin like that

You ain’t with us.

“You laughed, Your mama’s

Black as fuck. I turned. I quit.

I said what you said, held it up

To the sun to glint, then swallowed

It back down. You said, Child —

Black. You said, Cracker. You said,

Child — Out. Out.”

Similar to the onslaught of conflicting information facing the speaker in reference to his mother’s background, here the speaker faces an American context in which his identity is also called into question. The social constructions of race, language, and group identity the speaker inherits from his mother are further complicated where they come into contact with an American, and African American context.

These complications are further explored in the poem “A Mouthful of Salt…/ I Came through Numb Waters.” The narrator of the poem tries to make sense of concepts of race-based privilege as it intersects with his embodiment as a light skinned person of multiple racial backgrounds.

“I know my suffering is loud but my skin

is light as sky and I was told to let it

open doors, shake hands, slip the cover

over their eyes, so I could be. Free

is not a negro doused in white, blanched,

Bleached, and sent down the path. Free

Almost never means alive, so please try —

I’m asking for help.”

As this poem so painfully and beautifully demonstrates, the speaker’s light skin does not preclude him from experiencing the impact of painful histories in America, from being erased by multiple groups at once, or from suffering as a result of these ongoing legacies of pain, bleaching, and death.

These themes are further elaborated in the poem “Passing.” The speaker considers his reflection in the mirror, attempting to reconcile it with his identity as well as to see what other people see, or erase, in him.

“I laugh at the mirror, an animal,

unhinging, trying

to see what they see

in whatever I am standing here — Then

the train slides into a long tunnel.

The lights flicker off

and I am back inside my mother.”

This poem continues the theme of spaces that shift between light and dark, Black and white. The window from “The Most Opaque Sands Make the Clearest Glass” becomes a mirror. The mirror here, however, proves incapable of showing the speaker’s true image or even the image other people see when they look at him. The mirror offers no answers, and the only consolation comes when the lights go out and the speaker returns to his mother.

The poem “Single File” delves into a similar space, as the speaker relocates and reaffirms the spaces he sees in his mother, finding and acknowledging their echos in his own experience and embodiment.

“The black slipped back into the body and suddenly I

Carried no weight at all, no memory

Of days drenched in white, no desire to white,

Because I was, I was

Becoming the dark thing they had never wanted me to be

And was, always,”

Through acknowledging that he “was, always” the “dark thing they had never wanted” him to be, the speaker is able to become and to be who he is in a full and embodied way. As “The black slipped back into the body,” the speaker is able to shed the weight of his experience of being erased. He is able to embrace aspects of his identity and heritage that were not available to him previously.

We see similar themes in the poem “Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.” This poem incorporates the speaker’s physical experience of trauma, in the form of life threatening injury, into the existential trauma of having his identity repeatedly called into question and erased.

“as the eye

after the shock flash

still sees

the lightning.”

Light in this poem recalls the imposition of whiteness and the violence done to the speaker by the shock of the white light and the afterimage it leaves in his eye and consciousness. The trauma leaves an ongoing impact and an ongoing injury.

The title poem, “Into Each Room We Enter Without Knowing,” with its reference to the crown of sonnets, and its recurring motif of the blackstart, balances the pain of liminal spaces inhabited by the narrator of these poems with the exuberance made possible by the same spaces. This poem in four parts ties together themes from the sections of the collection, ranging from a young man’s awakening in a queer space to scenes of Muslim life in the Middle East, to another young man leaving his mother’s house to go off on his journey to the city.

In the first section of this poem, we watch a young man enter a club,

“Ecstatic, he lurks into the back room,

slipping his tongue

through the body’s shutters.

Floorboards unhinge. A skein of teeth unravels.

What pattern of occasion will free him?”

The next section, referring to the crown of sonnets, repeats part of this line, the word occasion,

“A prayer rug for a strict occasion.

A patch of sand, enclosed within a mesh fence,

where women in headscarves kneel in sajdah,”

We witness a prayer space as a woman kneels on a prayer rug. This section of the poem ends on,

“the grapes never to become wine.”

The next section picks up with,

“Eating grapes, my friend harangues me

About the state of affairs in Riyadh.”

The fourth section shifts from a woman buying meat at a halal butcher shop, to the image of Mohammed waking in the desert night, and again to the woman’s son on a journey similar to the young man that begins the poem series.

“ and as the mother exits

Another boy begins his journey to the city,

wearing yellow sandals and a ring on each finger.”

The sequence of the title poem forms a map of sorts to the collection as a whole. It encapsulates the themes of coming of age, navigation of the mother-child relationship, ties between far ranging geographical, cultural, and linguistic landscapes, and the intersections between embodiment and identity. At the same time that these spaces entail pain and trials, they are also spaces of exhilaration and the joys of self-discovery. These are frameworks which allow the speaker to challenge the erasure of his heritage and identity, and to reclaim and embody his own hard-earned frame of reference.

The poem “Trying to Live” brings up this frame of reference, tying it into the concept of colors and living spaces.

“I want to enter my life like a room. Blue walls.

A floor painted green. Three large windows. Light.”

Unlike “Self Portrait In Black and White,” the colors here are not a part of the problem, they are simply colors. The windows are not opaque sand burned into transparent glass. The light also is simply that — light. The space here is transformed into a room of light and color and possibility. This is not a room where the speaker is trapped or erased or reflected inaccurately. This room, and this life are the speaker’s own creation, full of potential.

Into Each Room We Enter Without Knowing contends with and elucidates marginal states inhabited by children of the North African diaspora, Americans of African descent, individuals of multiple racial, linguistic, and regional ties, and queer people who find themselves within these spaces. The speakers of these poems embody gaps between generations, regional and linguistic dislocation and diaspora, and the will to challenge erasures and define their own identities. In these precise and lovely meditations on the reclamation of identity, Shanahan compels the reader to reexamine the elements of light, darkness, and color, and to reread the transparency of glass and the face in the mirror.

Does that not make me — was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.