Arturo Desimone’s series on Latin American poetry, for Anomaly

Valparaíso-Bound: Neruda’s Ark

SS Winnipeg was Neruda’s Winged Fugitive Ark for war-refugees. Where are such grand gestures today?

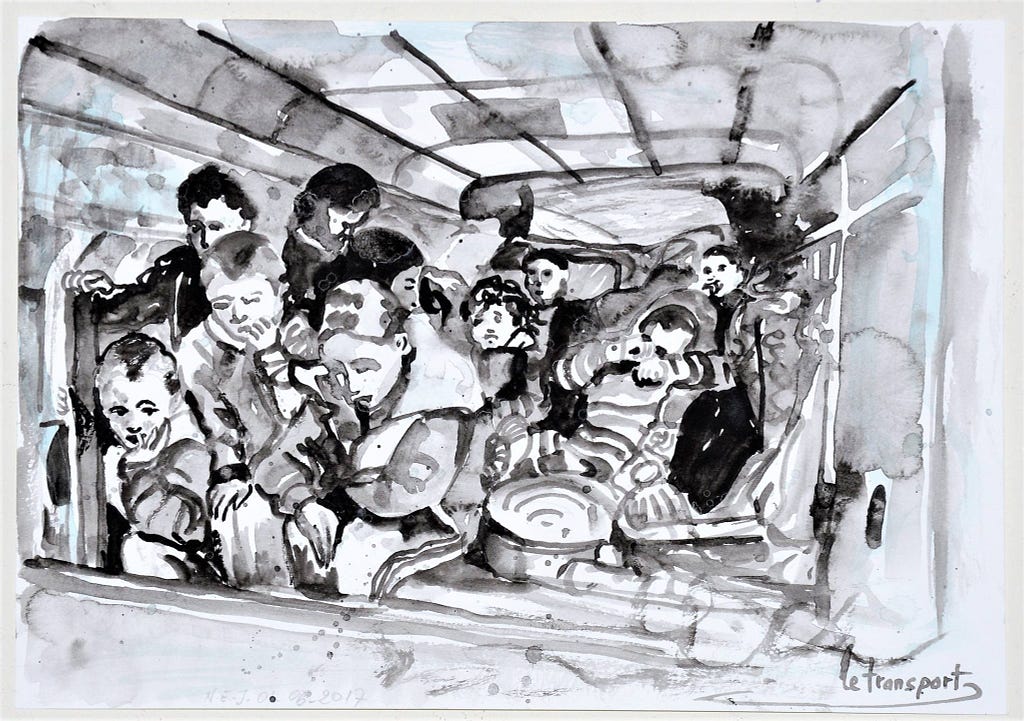

Stateless and dispossessed persons in the world today amount to a towering 65 million. If we are to trust the ‘’census’’ of such an unstable and stateless population, it is the highest number of refugees in recorded history (at least, in history recorded after the infamous case of Babel.) The scattered ones mount shouldering upon the flotillas; upon the waves, burnt by exposure to the wind and seawater, the cold, the sun and coast-guards, and under the Greek and Semitic constellations. On the shores of Europe, the shipwrecked either hide from the immigrations police, or are processed by techno-bureaucracies. A resident status is ‘’pending,’’ assets confiscated in storage facilities; petitioners are confined in the forced passivity of detention centers. Many years go squandered, lost in waiting. Waiting, during a grueling process for the approval or denial of refuge, by way of forms to be filled and email telegrams to be telegrammed. Waiting, to hear from relatives who fled, who did not flee; who may have died or who may have received a permit.

Poets around the world attempt to make poetic gestures of solidarity with the oppressed immigrants in what has become, ironically, the anti-nomadic world of globalized technocracy. Most of these poets’ activistic statements fall like dim arrows thrust against the currents of the dominant news media, its language, its software programs of noise-creation. Powerful interested parties try to generate panic about “refugee crises.” And many first-world, cultured liberals and card-carrying progressives who supported mass-deportation policies in the past, today accuse the right-wing extremists of being the original xenophobes (intellectuals who have decried such easy equations include philosopher Alain Badiou). Europe’s Uniformed guardians call this Philanthropy, speak of Generosity and its limits; while they wag their truncheons and their batons to no melody, only the disciplinarian harmony. Too often, poets end up servicing such easy apologetics. Looking to the historical example of Chile’s Pablo Neruda might provide lessons in spectacular solidarity.

Where is Winnipeg, during today’s 21st century refugee crises?

“You will ask why his poetry

doesn’t speak to us of dreams, of the leaves,

of the great volcanoes

of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets,

come and see

the blood in the streets,

come and see the blood

in the streets!”

(poem citation from Donald Walsh’s translation of “I Explain a Few Things’’)

When Chilean poet Pablo Neruda was his Andean republic’s ambassador to Spain, it was no longer the typical ambassador’s existence of lunches, dinners, opera and bullfights. Neruda found himself in the crossfire, between Fascist phalanxes’ counterrevolutionary retaliations and the Republicans. There were rumors of concentration camps for Spanish Republican captive families, controlled by the Fascists along the French border. Pablo Neruda — adopted name of Neftali Reyes — was the poet who had championed the warriors of Arauco and Lautaro’s legendary resistance against the first Spanish colonists. Now, in Europe, he came under pressure to make his actions live up to his own plumed bravado.

Neruda acted.

He acted with urgency to defend his friends. Many of these were Spanish poets in the resistance such as Rafael Alberti, who asked the Chilean consulate an absurd-seeming question “Why not make a Red Horse?” as if a poet could build a Trojan Horse to lay at the gates of Fascism. Neruda’s friend Federico García Lorca was murdered by Franco’s Moroccan brigade.

From Donald Walsh’s translation of Neruda’s I Explain A Few Things:

Federico, do you remember

under the ground, do you remember my house

with balconies where June light smothered the flowers in your mouth?

Brother, brother!

Neruda had his eye on an old navy ship, SS Winnipeg — originally a French cargo steamer built between 1914 and 1918, first christened as the Jacques Cartiere. Before the ship was sold to Canada, it would be used for the clandestine Chilean mission.

SS Winnipeg, Neruda’s ark, would transport Republican refugees to the harbor-mouth of Valparaíso, just North of Santiago on Chile’s coast.

“Operation SERES’’ (acronym meaning ‘’beings’’) would be the name of the mission. The poet-diplomat campaigned in Argentinean cities like Rosario, Córdoba and Buenos Aires. (All of these cities were almost entirely built and populated by immigrants, many of them of Spanish and Italian origin).

Neruda raised funds from provincial governments eager to accommodate refugees and with strong ties to the Republican cause. An everlasting enmity towards the Spanish Crown — seething ever since the first bourgeois creole uprisings in the Americas — also helped garner solidarity with anti-Royalism. SS Winnipeg, a barge populated by the refugees, docked in the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe before continuing to the arctic of Argentina’s Southernmost cape of Tierra del Fuego, then to the Pacific port of Valparaíso, Chile.

Winnipeg, Where Art Thou in 2017?

From Neruda’s letter in defense of the Winnipeg:

“Before my eyes, under my oversight, the sea-craft needed to be filled with 2000 men and women. They came from the concentration camps, from inhospitable desert regions. They came from fear, from defeat and that boat had to be filled with them, to bring them to the beaches of Chile, to my own familiar world, where they could be received, open-armed. They were the Spanish combatants who had crossed the French borders towards an exile outlasting 30 years”

Neruda’s poetry from the civil war period in Barcelona tell of an internal transformation — more seismic and powerful than mere catharsis — bringing him to act on behalf of others and of the oppressed. For a moment, the poet who at least compared himself to Jupiter, overcame his ego, or made his megalomania into a source of superhuman altruistic gestures (the SS Winnipeg was one of these.)

“My house was called

the house of flowers, because everywhere

geraniums were exploding:

(…)

“And one morning it was all burning,

and one morning the fires

came out of the earth,

devouring beings,

and ever since then fire,

gunpowder from then on,

and from then on blood.

Bandits with airplanes and Moors,

bandits with rings and duchesses,

bandits with black-robed friars

blessings came through the air to kill children,

and through the streets the blood of children

ran simply, like children’s blood.

Jackals that the jackal would spurn,

stones that the dry thistle would bite spitting,

vipers that vipers would abominate!

Facing you I have seen the blood of SyriaSpain

rise up to drown you in a single wave of pride and knives!

Treacherous generals: look at my dead house, look at SyriaSpain broken”

A shadow side exists to the story of Winnipeg: according to Neruda-biographers David Schidlowsky and Adam Feinstein, Neruda was highly selective of the ideologies of those refugees he helped. That meant no anarchists and no outspoken Trostkyite or left-communists on board: only those towing the hard Party line. Anarchist leader Joseph Pierats managed to get on anyway. But one known Trotskyite painter, Eugenio Fernandez Granell, was invited to disembark in Santo Domingo in the Caribbean. Neruda might have been a minor tyrant on board Winnipeg.

Winnipeg was exceptional, the kind of spectacle that remains a tradition in Chilean poetry (like when Raúl Zuríta famously wrote a cloud-poem with a small airplane over the Atacama desert).

But Latin American countries like Argentina, Uruguay, Ecuador and Brazil have long histories of immigration and open border policies. Conventionally, Latin American authorities deported only in response to extradition orders in cooperation with foreign courts for serious crimes (homicides, drug trade investigations) but not for the mere act of wandering. To punish the act of wandering, or to demand that only physical danger or the threat of annihilation justify migration, is to punish wanderlust and curiosity itself in the human psyche. Such repression is one of many reasons why poets and humanity should take immigration-politics seriously.

Today’s Chile sports the largest Palestinian community outside of the Arab world, roughly 500.000. Argentina, meanwhile, has the third largest Jewish community in the world and is also one of the major centers of the Armenian, Syrian diasporas though it is more often associated famously with the Italian and Spanish civil-war era diasporas.

In Argentina — a nation built by immigrants and refugees, the first immigrant detention centers in memory begun to be constructed in 2016 by president Mauricio Macri — himself the son of a South-Italian Calabrese immigrant to Argentina, married to Juliana Awada, of the prominent, integrated, successful Syrian community of Argentina. President and first lady toured Northern European countries such as the Netherlands, Denmark and Switzerland last Summer, in awe of what Latin American elites consider to be the advanced societies of the North. Though entrepreneurial president Macri says he’s at odds with Trump and is married to a Syrian-Argentine, he was most impressed by European willingness to plainly criminalize the act of wandering. The yet-inactive deportation center in Argentina, however, was meant for Paraguayan and Peruvian immigrants: the government gave refuge to Syrian families, but remaining true to its free-market ideology offered no facilities to assist the Syrian refugees’ adaptation to Argentine cities like Cordoba, leading some families to return to their country at war (as chronicled in Spanish newspaper El País) Overthrown Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff, in 2015 had extended naturalization to 40.000 Haitians before the 2016 coup.

Even though the refugees Neruda then transported were a relatively tiny number — 2000 — compared to today’s world of 65 million stateless and displaced persons, the Winnipeg grand gesture is still of resonant value: it synthesizes the historical role of Latin American countries in receiving refugees.

That role was paralyzed by the right wing successes in Latin American politics in 2016, such as the election victory of Mauricio Macri in Argentina, and the coup in Brazil. Before 2016, the left-leaning establishments of Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Venezuela had all made statements of willingness to receive the exiles, though there was also reason to be skeptical of their seeming hospitality, for example: this article in the Argentina Independent by Peter Lykke Lind. In all likelihood, the Left in Latin America wanted to bide its time, waiting until after the election season to then embarrass Europe with open-arms in sheltering the war-refugees. But the string of electoral defeats as well as coup and failure of the left have unfortunately postponed Europe’s and the USA’s timely embarrassment in the “refugee crisis,” a crisis of solidarity.

Concluding this post in the series NOTES ON A JOURNEY TO THE EVER-DYING LANDS is my translation of Neruda’s letter. The grand humanitarian and socialist achievement of his career, the captaining of the SS Winnipeg, was cause for Neruda’s satisfaction not least of all with Neruda himself. Mid-letter, the poet compares himself to the Roman god Jupiter/ Jove, elsewhere to the Biblical creator of the book of Genesis, who rested on the seventh day. Neruda’s statement confirms his the rumors of the poet’s virile megalomania. Yet there is little doubt, Neruda’s megalomania here was heroic; his crystal-jeweled pomposity proved revolutionary. Are such feats possible without hubris? If we had a consecrated poet like Neruda today, amidst the horrors of displacement, then the silliness of official art-world posturing would look charmless by comparison. Instead of Neruda’s imitation of Noah or Moses, the subversions are mostly like those of Ai Wei Wei, based on the media-aesthetics of farce and politicized parody.

“From the beginning I liked the word Winnipeg. Words either have wings or they don’t. The word Winnipeg is winged. I saw her sail for the first time in a misty harbour, near Burdeos. It was a beautiful old ship, wearing that dignity obtained from the seven seas over the course of time….

Before my eyes, under my oversight, the sea-craft needed to be filled with 2000 men and women. They came from concentration camps, from inhospitable desert regions. They came from fear, from defeat and that boat had to be filled with them, to bring them to the beaches of Chile, to my own familiar world, where they could be received, open-armed. They were the Spanish combatants who crossed the French borders, into an exile outlasting 30 years.

“I did not believe, when I traveled from Chile to France of the adverse circumstances, of the difficulties that I would encounter in my mission. My country needed qualified, capable men of creative will. We needed specialists.

“To gather up those wastrels, those poor souls: to pluck them from the most remote encampments and to carry them off; on that azure day in the sea of France, where the Winnipeg gently moored: this was a grave matter, this was a complicated matter, entailing work motivated by devotion and despair.

“My aides were a sort of tribunal from purgatory. And I, for the first and last time, must have resembled Jupiter to the emigrants. By decree I issued the final Yes and the final No. But, in a sense I am much more Yes than No — for I almost always said, YES

“We were already almost filled to the brim, with all my good cousins: pilgrims heading unto unknown lands. And I prepared to rest from the difficult Task, but my emotions seemed interminable as ever. The Chilean government, embattled and under pressure, urged me in telegrams to cancel the journey of the emigrants.

“I spoke to my country’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Long distance communication was difficult in 1939. But my indignation and my anxiety were heard: across oceans and the mountain ranges, and the Ministry gave up, in solidarity with me. After a crisis of the Cabinet, the Winnipeg, carrying two thousand republicans who sang and cried, unhinged anchors and endeavored the route to Valparaíso.”

“May the critics erase all of my poetry, if they deem such erasure to be merited. But this poem, which I recall today, is one that nobody will ever be able to erase’’ — wrote the poet about the diluvian feat, afflicted perhaps by the Biblical alcoholic Noah’s nightingale; or by a Moses-complex, at the very least. Neruda still tried to play the ideological police on board; today’s Western rescue-missions are no better, and probably much stricter in that respect.

Author’s Notes:

- The Winnipeg is commemorated after 75 years of its arrival to Chilean coasts

- Nuestro.cl /Winnipeg: The poem that crossed the Atlantic

- speech at University of Washington 2007, Reed/Osheroff lecture, Pablo Neruda, Spanish Civil War,

- La otra historia del Winnipeg: los que Neruda excluyó

On the blogger behind “Notes on A Journey to the Ever-Dying Lands’’

Arturo Desimone, Arubian-Argentinian writer and visual artist, was born in 1984 on the island Aruba which he inhabited until the age of 22, when he emigrated to the Netherlands. He is currently based in Argentina (a country two of his ancestors left during the 1970s) while working on a long fiction project about childhoods, diasporas, islands and religion. Desimone’s articles, poetry and short fiction pieces have previously appeared in CounterPunch, Círculo de Poesía(Spanish) Acentos Review, New Orleans Review, DemocraciaAbierta, BIM Magazine and forthcoming in MOKO , Matter Monthly, and Island.

Notes on a Journey to the Ever-Dying Lands was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.