A Gentle Visit

“The visit was a liniment,” writes poet Alberto Ríos in “Coffee in the Afternoon.”

A balm for the nerves of two people living in the world,

A balm in the tenor of its language, which spoke through our hands

In the small lifting of our cups and our cakes to our lips.

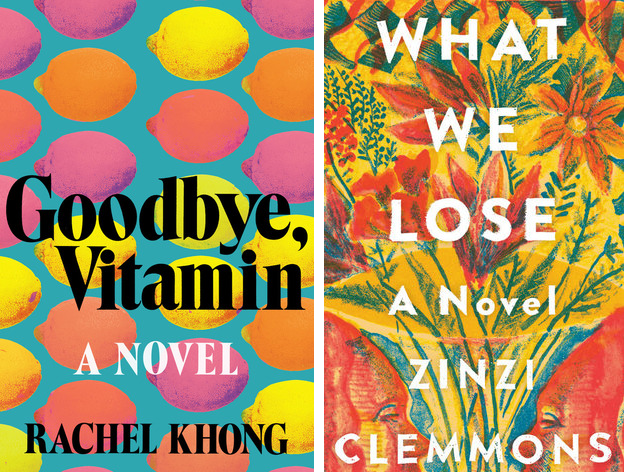

I was reminded of this simply-worded poem by two debut novels out this month — Goodbye, Vitamin by Rachel Khong, and What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons. Both read like well-documented, thoughtfully worded journals. Both deal with memory, the loss of a parent, and the importance of food when trying to cope and heal. And yet, they are completely different in tone. Where Khong is light-hearted and sweetly mournful, Clemmons is darkly emotional, connecting her personal loss to the bigger issues that have shaped her family and life.

English speakers (myself included) often slip and use “where” when referencing time. “There was this time where,” I’ll say, and catch myself, my mind fumbling to make the seemingly logical correction to connect time to “when,” to place it on a line rather than in space. But don’t we see time as physical? Who hasn’t gone back to their childhood bedroom and felt herself transported to the time-space contained there? In close relationships, we contain time for each other, storing memories jointly. This concept, called transactive memory, was proposed by social psychologist Daniel Wegner in 1985. It seems this is why other people can take us back in our minds — we’ve shared a significant event or portion of life, and so they own some of the recollections. So, what happens when a person close to us, who has been this kind of home to our memories, dies?

So much of memory is dependent on recording. We retain moments by giving them language, and transcribing. This is what Goodbye, Vitamin protagonist Ruth does for her father. A historian, he is a practiced record-keeper. As he slowly succumbs to Alzheimer’s, Ruth finds diary entries of his, all concerning her, left here and there throughout her parents’ house. This is also the form the novel takes: told in a year’s worth of Ruth’s dated diary entries. Khong’s genius is conveying family moments without evoking cringe. “Tonight I peeled peaches and we sat beneath the mostly done pergola,” Ruth logs on July 11th, “and in the moonlight your face was tired and lined like the underside of a cabbage leaf and I wondered what I looked like to you.” This feels genuine and sweet. Ruth’s father’s memory-keepings feel similar:

Today you asked if I’d ever watched a moth eat clothes and I replied honestly: no.

Today you said you didn’t believe it!

Today you admired a magnolia tree and I told you it was one of the earth’s oldest plants, that the flowers are so big because beetles used to crawl into them carrying the pollen on their legs. And you asked, Why should I believe you? And that was a very good question.

Ruth and her father are mapping each other in reverse — he records her learning and becoming; she records his devolution. By taking note, she’s preserving the pieces being lost as his mind fails. We often hear about loved ones “living on” in the memory of their families. This is what Ruth dutifully ensures. One of the amazing things about this book is that Khong takes her readers to such depths while remaining ever light on her feet (often causing me to laugh out loud). Though written in first person, no ego comes through. It’s a strange relief to discover that a voice can be both strong and quiet, and Khong achieves this joyous depth even while writing about one of the hardest experiences a person can have.

Clemmons takes up a similar project, but with an entirely different tone. For her narrator, Thandi, What We Lose is the place to dispel grief over losing her mother. The book is populated by chunks of blank space, excerpts of outside text, and caption-less photos, through which Clemmons conveys a mindset complicated by the politics of race and gender. Thandi is the daughter of a South African mother and an American father. Her family is well-off, educated, and cultured, yet she frequently feels a strong sense of unbelonging. “I’ve often thought that being a light-skinned black woman is like being a well-dressed person who is also homeless,” she thinks.

She sometimes avoids further complicating her identity for others. Her classmates conceive of Africa as it is depicted by National Geographic — grass huts, poverty. Thandi’s family has a vacation home in a rich neighborhood near her mother’s family; she doesn’t correct their worldview.

Clemmons takes on so much, and writes with such nuance, that it’s difficult to fully describe What We Lose. One of the strongest meditations throughout the book is on motherhood. Thandi examines her life as she thinks her mother would, frequently recalling things she taught her, or advice she gave. Clemmons captures motherhood well — the fondness that a daughter can have for the person whose politics and worldview she’s moved beyond.

The meditation is made deeper by Thandi’s pregnancy. As she is grieving her own mother, she is becoming one. The book’s language often veers mathematical, leading to Thandi’s interesting take on her grief, which she depicts in several graphs, and in this description:

At the point of her death, a line circles inward into itself to infinity, disappearing into infinite fractions. It was so beyond comprehension and feeling that it wasn’t able to be captured on a plane of ‘hurt’ or ‘sadness,’ or any single human emotion.

This logical remove is part of what sets the tone. Thandi doesn’t just believe in a story or concept, she chooses to believe, as when, after her mother has died, she engages with the idea of her ghost, letting it comfort her. Here and gone aren’t always hard facts. In a section that reads like poetry, Clemmons writes, “She’s gone,” but then follows with six tiny paragraphs, each beginning with “but” — “But she’s here, I can feel her.” Even as her mind articulates reality, it also protests it. Clemmons defines Thandi’s heartbreak this way:

Your heart wants something, but reality resists it. Death is inert and heavy, and it has no relation to your heart’s desires.

Khong and Clemmons show that some of the best novels can feel like very good conversations. They’re amusing, contain much substantive information, but not so much that they overwhelm, and they’re gentle: strong-minded, but not argumentative. Rachel Khong’s sweet debut, Goodbye, Vitamin, has this quality. It’s comforting and soft-voiced, like the friend whose calls you never ignore. Zinzi Clemmons achieves the sentiment Ríos conveys in the last lines of “Coffee in the Afternoon”:

It was simplicity, and held only what it needed.

It was a gentle visit, and I did not see her again.

A Gentle Visit was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.