“what is left is only water:” Navigating Exile and Distance in The January Children, by Safia Elhillo

i am not named in the very first language i call arabic my mother tongue

& mourn only that orphaning i mime

i name nubia & hear only what i cannot speak

– “self-portrait with lake nasser”

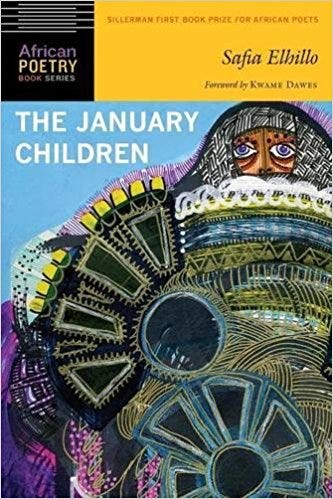

Safia Elhillo weaves layers of language and exile in this haunting tribute to family and histories of Sudan and Sudanese diaspora. Her unflinching gaze links together the plaintive lyrics of Egyptian singer Abdel Halim Hafez, sonic resonances between the Arabic words for love and wind, and testimonies of loss, occupation, and government oppression in Sudan.

The opening page elucidates the title and the vocabulary words أسمر :/as•mar and أسمراني :/as•ma•ra•ni/– the former describes children born under British occupation in Sudan, and the latter refers to the words of a well-known song by Hafez, addressed to a dark-skinned woman. This song serves as a negotiating point for the identity of the narrator of the poems.

Elhillo’s collection sings a love melody to the Arabic language in all its complexity, from Qur’anic verse, to Egyptian songs, to Sudanese colloquialisms. With the exception of one erasure poem, the poem titles are all in lower case, elevating the unicase system in Arabic writing. The first poem, “asmarani makes prayer” opens with the Qur’anic poetry formula, إِنَّ / verily — “& verily a border-shaped wound will / be licked clean by songs naming / the browngirl.” These lines balance between words and pauses, Sudan, Qur’an, and diaspora, and resonances between English and Arabic.

The next poems lay out the stakes involved in the narrator’s navigation between languages and aspects of Sudanese identity. The poem “vocabulary” delineates the fine line between the words for love and wind in Arabic,

“Fact:

the arabic word هواء /hawa/ means wind

The arabic word هوى /hawa/ means love”

This poem explores ways in which this near homonym might impact the meaning of songs by beloved Arabic language singers including Fairouz, Hafez, and Oum Kalthoum. By reading lyrics with hawa meaning love, and then with hawa meaning wind, the narrator shows us how the same line can mean its opposite. These lines also play with the common Arabic expression, kulna fil hawa sawa, which could be read either as we are all the same in love, or the same wind blows us all.

The collection acknowledges some of the complexities of Arabic directly in the erasure poem “Sudan Today. Nairobi: Univerity of Africa, 1971. Print.” which offers,

“Note on Arabic.

It is difficult.

The Publishers do not pretend

to have solved the problem.”

Reading Elhillo’s tautly woven and sonically lovely collection, it would be easy to miss how difficult Arabic can be, and how much work must have gone into the act of balancing and stitching together such range of both Arabic and English languages.

The poem “glossary” provides an example of subtle linguistic shifts between and within language. Presented as a chart, which could be read in several possible directions — by row, column, or diagonally, and equally fascinating in any of these readings, the poem provides examples of colloquial expressions in Sudanese Arabic. Among these, we find,

“موية زرقة /moya zarga/ blue water drinking water

الموية البيضاء /al-moya al-beidaa/ the white water cataracts

الموية السوداء /al-moya al-sowdaa/ the black water blood in the whites of the eyes”

Themes of water and slippage between meanings become necessary to understanding the relationships between sound and meaning, what is said and what is meant, and gaps between literal meaning and metaphor.

The speaker’s relationship with Abdel Halim Hafez and his songs of longing also hinges on nuances of metaphors and the demarcation of their possible meanings. She questions whether she might be the asmirani woman addressed in the songs. The poem “abdelhalim hafez asks who the sudanese are” takes us through several related considerations, including the definition of asmarani,

“أسمر :/as•mar/ adj. Dark-skinned; brown-skinned

أسمراني :/as•ma•ra•ni/ diminutive form of أسمر

” أسمر يا أسمراني / مين أساك عليا“

“brownskinned one / what makes you so cruel to me”

This poem ties into questions of identity and belonging that thread throughout the collection, as well as terms such as asmarani which have meanings difficult to pin down in Arabic. The same poem also roots for the source of the name Sudan, as well as the ways in which its people are positioned in the Arab world,

“جمهورية السودان: / jum•hūrīy•at as•sūdān/ republic of the sudan

بلاد السودان : /bil•ād as•sūdān / land of the blacks

from سود /sūd/ plural of أسود /aswad/ “black”

Both the word asmar and the word aswad (the root of the word Sudan) can mean black. In the same way that hawa can mean either wind or love, based on a minor vowel change, the terms asmar and aswad carry the same broad meaning, if not the same connotations. In examining the context of the song, the narrator concludes,

“[don’t think he means you don’t think he means black]

[in context / asmarani / means something closer to swarthy]

[closer to a girl who can run a comb through her hair]”

These lines sew together a fine sound repetition with a balanced tone to deliver a crushing conclusion — not only does the term asmar seem to exclude the speaker, there is also an implication that Hafez would not recognize her as either his asmarani or as having an identity tied to Arabic. This poem points out the ways in which the term Sudan is marked in Arabic as singling out and excluding Sudanese people from identifying as Arabs. The speaker’s intricate knowledge and exploration of Arabic serves to highlight the ways in which she is excluded from the language tied to her family and their country of origin.

The speaker of “self-portrait with the question of race” examines further this rift embedded in language,

“عِرِق:/ʻi•riq/ n. race; vein; SUDANESE COLLOQUIAL derogatory

african blood; black blood.”

Here the Sudanese colloquial term adds a further layer of meaning, associating the term for race with negative terms for African people, as though other Arabic-speaking people don’t have race. The poem also makes a pointed aside in the form of advice to a parent,

“[but your daughter will be fine but keep her out of the sun but do something with that hair or people will not know she is بنت عرب daughter of arabs]”

These casually mentioned colloquial phrases drive home how much pressure the speaker and her family are under to prove or perform their belonging to the only culture and language left to them.

The spare and haunting poem “self-portrait with lake nasser” dredges up an earlier colonization from the meeting point between the blue and white nile,

“try it like this there was once a world

& then there was only water its fat & clouded body

traded in our old languages to start again as arabs [but not quite]

[بلاد السودان : /bil•ād as•sūdān/ land of the blacks]”

In this evocative and visceral poem, we see the ties between colonization, geography, and man-made impositions on the landscape. The idea of trading in old languages points both to lost language as irretrievable, and to the speaker’s claim to these languages, even in their absence. The spaces in this poem and the bracketing of phrases underline the gaps between the old languages and starting again as Arabs, the Arabic language marking of Sudan as the land of the blacks, and the flooding of specifically Nubian land with water as the Aswan Dam was built.

The relationship between the poems’ narrator and Abdelhalim Hafez also navigates rifts of space and language. In the poem “abdelhalim hafez wants to see other people,” the speaker asserts,

“i am not lonely i have ghosts

i have my illnesses i have a mouthful

of half-languages & blood thick with medication

doctors line up to hear my crooked heart”

This poem creates a world in which illnesses and half-languages keep the speaker company and mark her as unique and miraculous. The sound repetition, the striking images, and the juxtaposition of concepts turn this list of reasons not to be lonely into a full world of its own, where a mouthful of half languages and blood thick with medication become resources and forms of identity.

We also see navigations of identity in relation to Hafez in the poem “why abdelhalim,” when the speaker elucidates some of the points of convergence between herself and Hafez. She asserts,

“he dies before

belonging he belongs to no one country [same]

he belongs to no one language [check my mouth]

he belongs to no one in this way he never leaves”

While, as we see in other poems, there are still disjunctures between the asmarani and the narrator of the poems, we see that the songs, persona, and personal history of Hafez tie in very closely with multiple forms of belonging to countries, languages, and other people. The bracketed “[check my mouth]” also creates a resonance with the idea of a mouthful of half-languages and with the image of doctors lining up to examine the speaker.

The narrator of these poems delineates a full world in the borders between languages, countries, and the people associated with them. The poem “others” reinforces the narrator’s resistance to being corralled into ill fitting categories or reduced to a single language on other people’s terms. The speaker asserts,

“you wake & i am crying &

will not let you hear the song you wake &

i am praying shaping incantations

with my mouth & never offering to translate”

Here, the multiple half-languages become prayer, incantation, song. The speaker presents these as complete in themselves and refuses to translate them for the listener. These lines lay out the intricate work Safia Elhillo has done in creating this astonishing collection of poems.

To write a poetry collection in languages closely related to each other is challenging enough. The complex interweaving of multiple Arabics with English that Elhillo accomplishes in these poems is beyond difficult. Her refusal to compromise one language for the others, and her interweaving of layers and registers of each language add a necessary voice to American and Anglophone literature.

The silences in this collection also speak to this conversation, whether they mark gaps between languages or the violent erasure of Nubian land and language tied to the flooding of the Niles by the creation of the Aswan Dam. Translation too reveals its complications and contingencies as these poems move within the meanings associated with a single word or phrase. What Hafez means by asmarani is not the only possible meaning for the word, nor does Hafez belong to any one person or group.

The January Children resists the marginalization of its narrator and the reduction of her world to a border region or a half space. Elhillo claims the space marked by multiple colonizations and erasures, histories of diaspora and exile, and the linguistic landscape in which this space occurs. This collection commands an arena of its own in poetry, and opens space for further creative work, much in the way that works like Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands / La Frontera, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictée, and Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf broke language and genre barriers in American and Anglophone literature, as well as inspiring generations of writers. Elhillo has done a great service for readers of English, and for writers who work multilingually. The January Children confirms that we can expect great things from Elhillo as a poet and as a leading voice in American literature.

“what is left is only water:” Navigating Exile and Distance in The January Children, by Safia… was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.