Can one part of the mind stay awake, while another dreams? How do daytime impressions filter and condense into meaning? What is the link between consciousness and unconsciousness at the personal and collective levels? Oneiromancy, the study of dreams, asks questions about the sleeping mind and its layered meanings; rigorous scientific technique is applied to abstract and nebulous material. Such study in part has a practical purpose — the hidden stuff of the mind is valuable in creating prophecies for the future about the essence of the individual and History.

A long, rich tradition of dream interpretation stretches from the Greeks to the Indians, from mystic Jewish Kabbalah to the books of the Qu’ran. But beyond the great systems, many individual forays have also been made into dream science, to build up a powerful personal arsenal of symbols. The work of Chilean poet Winétt de Rokha is a prime example.

Winétt wrote several books of poetry in her life, but today she is still best known for being the wife of Pablo de Rokha, one of the ‘big four’ in Chile along with Neruda, Huidobro, and Mistral. Winétt met Pablo after she wrote him a letter to say that she liked his work, and he fell so deeply in love with her words that he came to her little town to ask for her hand. Her father refused, and Pablo challenged him to a duel. Impressed, her father let him marry the girl.

The work of Winétt is usually divided into three phases — naive feminine poems, political poems, and cryptic surrealist poems. Oniromancia [Oneiromancy], her penultimate book of poetry before the modernist volume El valle que pierde su atmósfera [The valley that loses its atmosphere], is very visual and dreamlike, as its name would suggest. In it Winétt builds up a personal mythology, with a tone that is very lush, what those accustomed to sparer and more dry style might even call purple. It is a kind of prose that demands you to sink into it.

Oneiromancy is a short book of poems, and not necessarily a happy one. A great deal of pain is compressed into its pages. In fact, it is almost unbearably difficult to read and translate. The ‘true story’ behind the text, so far as it matters, is the affair of Winétt’s husband Pablo with a beautiful Greek woman visiting Chile. It was not the first of such affairs on his part, but this one seems to have affected her with particular intensity, and the observation and aftermath bear their influence on its pages.

In a sense, this is a book that attempts to understand what has happened, in language that while not entirely cryptic, obscures the event. Perhaps one can think of Winétt’s poems as an act of conservation, fragments of present emotion outlining a dream of happiness that had not yet come, either for her personally or for the society in which she lived. In Multitud, the magazine Winétt published with Pablo, the two opine on the Russian Revolution, the Spanish Civil War and the Popular Front, seeking patterns and progress in history.

This utopian dream of happiness is what Winétt’s granddaughter and a small but passionate band of others are trying to discover today. The Fundación de Rokha is located on calle Holanda in the Providencia neighborhood, in a house with a large front grille, across the street from a gas station. The foundation is under construction, perhaps its constant state of affairs.

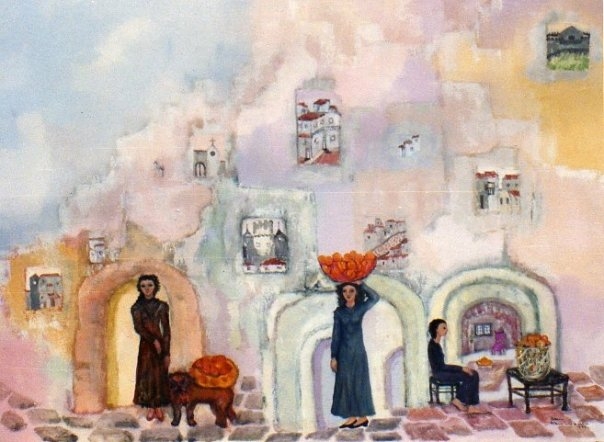

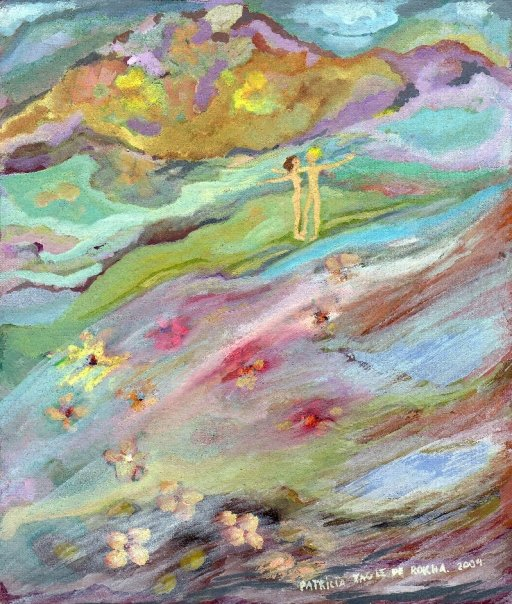

Patricia Tagle, the one who runs it, is an energetic woman with bouncy curls and an enormous smile. Like so many of the de Rokhas, she is an artist, with a fully de Rokha spirit. Her paintings, based in intuition, are a swirl of vibrant colors and spirits. When she shows me the work of another one of the de Rokha grandchildren, beautiful and elaborate puppets with round white faces wearing soft costumes covered in adornments, I recognize a similar aesthetic.

In ‘Song of the Puppets,’ Winétt writes of the moment that the ‘shabby and empty room, in loneliness, soaks into itself, and takes account of its shadow, like evening, when it looks into the perpendicular eye of the rivers.’ These are striking images, not only for the way they attribute consciousness to inanimate space (room) and time (evening), but also for the oppositions they set up.

The room recognizes the shadows within it, the absence of the cheering public. Vertical evening recognizes itself in the horizontal rivers that run over the land, which look back at her with their eye. Something looks within itself, and something looks below itself. Such spatial awareness makes one wonder what Winétt was looking at, and whether the self can be its own mirror. ‘Song of the Puppets’ is ultimately a song about the being on the empty stage, after the puppets have been taken away.

Winétt’s poems are influenced by the stories she heard as a child, such as the folkloric tales of Huan Li T’ou, Eglantina and Monita de Palo. In this last, a king falls in love with his daughter María and wants to marry her. She gives him a few seemingly impossible requests. First she asks him to make her a dress with all the stars in the sky. Then she asks for a bunch of singing goldfinches. In league with the devil, he is able to fulfill these requests. Desperate, María orders a monkey suit made, and escapes wearing it. She is found by a nice young man, who takes her to his mother’s house. The ‘monkey’ helps around the house, and in secret goes to church in the dress covered with stars and the bunch of goldfinches. There, the young man falls in love with her. Eventually it is revealed that the monkey is María, and she and the young man get married with a party that lasts for days.

Perhaps Winétt turns to myth as an alternative to the fact-seeking of her Irish grandfather Domingo Sanderson, the man she rebels against, who dedicates himself to erudite subjects of the Enlightenment and Counter Enlightenment. Fascinating as these topics are, buried in his yellow papers of the occult, he forgets how to live. Winétt rebels against this, though not entirely. Like her grandfather, she is on a quest, and she believes that some occult meaning exists beyond the surface of things.

Winétt wrote her little volume at home in 1942. The same year that she published Oniromancia, her husband Pablo published his Morfología del espanto. The hidden dialogue between their works was another occult element; the works of the two writers are in constant conversation, building up their own private world. The second essay of Pablo’s book, ‘Lengua y sollozo’, begins this way: ‘Overcoming errors and afflictions, Winétt, with her worldly accent, makes possible the great tragic and sublimely heroic magic of art, within which man constructs the anxiety and unity conceptualized by Cervantes, Job or Aeschylus, and links what is antagonistic.’

A recording exists of Winétt reading at the Library of Congress in Washington DC. Her voice is rich and deep, her tone assured. Yet what most calls the attention is how similar her cadence is to that of her husband. The question of whether Winétt transcended the role of muse and feminine support haunts her work, and remains a question for the academics and translators rediscovering her poems.

OTHER PARADISES: Dream Logic was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.