In this series, we listen in as Drunken Boat’s renowned translators talk with one another about art, craft, and the role of translation in the world. This third installment features Layla Benitez-James and Brendan Riley.

Layla Benitez-James (Austin, 1989) is a poet and translator living in Madrid. Her work has appeared in The San Antonio Express-News, The San Antonio Current’s Flash Fiction series, Acentos Review, Plaza: Dialogues in Language and Literature, Matter, Guernica, Autostraddle and a translation of Spanish poet Cristina Morano in Waxwing. Poems have appeared in translation into Spanish in Revista Kokoro, La Caja de Resistencia and La Galla Ciencia Numero IV with bilingual presentations in Spain including El Tren de los Poetas in Cuenca, Los Lunes Literarios, La Galla Ciencia, Café Zalacaín in Murcia, and La poesía es noticia: Moth & Rust / Óxido y polilla, una sesión de poemas en inglés y español in Alicante. Audio essays about translation can be found at Asymptote Journal, where she is the current Podcast Editor.

Brendan Riley holds degrees in English from Santa Clara University and Rutgers University. An ATA Certified Translator of Spanish to English, he has also earned certificates in Translation Studies from U.C. Berkeley, and Applied Literary Translation from the University of Illinois. Riley’s translations include Juan Velasco’s Massacre of the Dreamers, Álvaro Enrigue’s acclaimed Hypothermia, and Juan Filloy’s Caterva, as well as Sunrise in Southeast Asia by Carmen Grau, and The Bible: Living Dialogue by Pope Francis, Marceloa Figueroa, and Abraham Skorka. His translation of Carlos Fuentes’ The Great Latin American Novel will be published in October by Dalkey Archive Press.

Degrees of Separation

As part of Drunken Boat’s Translation interview series, Brendan Riley (Good Intentions by Juan Gómez Bárcena) and Layla Benitez-James (Man in Blue by Óscar Curieses) sat down together (in a manner of speaking, across time zones and many miles over email) to discuss their translations, published and forthcoming, in the journal.

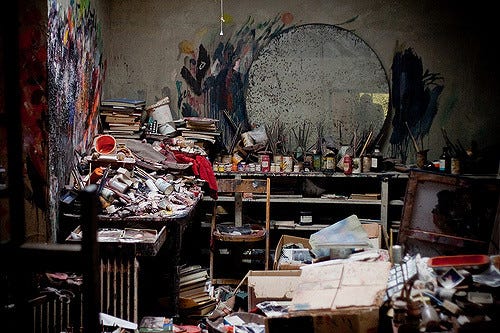

At first, perhaps casting about for a jumping-off place, two translators unknown to each other, thousands of miles and several times zones apart, wonder about points in common, lines of communication, how to proceed with an interview that requests insights into the translation process. But before that can happen both reckon with and reel a bit from the distinct oddity of their respective pieces, and both sense and see that what at first glance seemed possibly unrelated in fact do share an uncanny sort of connection; both Juan Gómez Bárcena’s story “Good Intentions” and Óscar Curieses’s novel Man in Blue drag the reader into unsettling interior spaces, the former’s an inescapable nightmarish house wherein a sadistic possibly unreliable adult narrator describes their daily routine “taking care” of their senile mother while the latter’s is the clutterhoard studio thicket of legendary painter Francis Bacon. The spooky echoes between these two places led both translators into exploring a series of associations that both works sparked for them, and the unexpected resonances of these artistic, literary, and cultural touchstones evolved into an interesting discussion on the act of translation.

This is less a conversation of specific elements of craft and more an illustration of the leaps and connotations forged in the mind of a translator at work or, perhaps, what happens to the mind of a translator when it is at rest.

Brendan Riley: The idea of Bacon’s studio being recreated in exact detail reminds me of Borges’ story “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote”; that by recreating the original we examine it more carefully, reveal, more about it. It also makes me think of Borgesian invention of imaginary texts.

The idea of Bacon being criticized for being like Walt Disney is hilarious. Is this true?

A crucial theme here is the notion of artist as self-curator, Bacon preparing for interviews, and how the published interviews (as stated) bear little resemblance to the recorded ones.

Also notions of filth, that the painter gets the paint on his skin, must get dirty for his art.

Many of the moments narrated in Juan Gómez Bárcena’s story could be one of Bacon’s screaming paintings. In what way doe JGB’s story go beyond satire? Bacon’s art seems both terrifyingly serious and terrifically satirical. I wonder if he influenced the work of illustrator Ralph Steadman.

Painting as skin, canvas as flesh, flesh being torn, canvas being torn. The artist tearing at himself as he tries to create a clear colloquy about the connection and distinction between what’s in his mind and what’s on the canvas. This also leads to the Beckett (echoic of Bacon) connection that appears in your translation. As Curieses’s Bacon writes in his journal:

[November 29th]

The protagonists of my paintings, if they speak, would do so in a similar manner to the works of Beckett. [11]

But unlike his, they would not be about something irrational or philosophical. In my paintings the characters are seen and act from the perspective of a hallucinating animal. There.

This brings to mind a signature episode in Molloy, another fraught parent-child scenario, when Jacques Moran has given his seemingly not-too-bright son instructions to walk to Hole and buy a bicycle, “second-hand for preference.” As the son leaves, Moran says:

I shouted his name. He turned again. A lamp! I cried. A good lamp! He did not understand. How could he have understood, at twenty paces, he who could not understand at one. He came back towards me. I waved him away, crying, Go on! Go on! He stopped and stared at me, his head on one side like a parrot, utterly bewildered apparently. Foolishly I made to stoop, to pick up a stone or a piece of wood or a clod, anything in the way of a projectile, and nearly fell. I reached up above my head, broke off a live bough and hurled it violently in his direction. He spun round and took to his heels. Really there were times I could not understand my son. He must have known he was out of range, even of a good stone, and yet he took to his heels. Perhaps he was afraid I would run after him. And indeed, I think there is something terrifying about the way I run, with my head flung back, my teeth clenched, my elbows bent to the full and my knees nearly hitting me in the face. And I have often caught faster runners than myself thanks to this way of running. They stop and wait for me, rather than prolong such a horrible outburst at their heels. As for the lamp, we did not need a lamp. (Beckett, Molloy, 144).

Beckett’s protagonists spin in the psychosis of mental permutations. Moran descends into a kind of psychosis, at the command of an inner-voice. Moran, if painted the way he describes himself running, would make a very Baconian image indeed, full-flight frozen frenzy.

Curieses/Bacon also expresses the notion of painting as mirror, as a truer self than the artist/author because it’s a reflection of the moment, stands apart from time, while the artist goes on changing. Bacon says that Rembrandt wins because the living Rembrandt is gone, what lives on are his perfect self-portraits. The living Bacon, reflecting on his portrait, and himself, must conclude himself in an inferior position.

It’s the conundrum between artist and artifact; people see the artifact and expect that it is the artist, that the artist must be like what they create, must be what they create, and the artist who falls into that trap loses and is lost because the true artist lives for the day and goes on changing, goes on creating, the artifact is a reflection of the moment.

Moran, whose philosophical musings are a kind of syntactical worm coursing catechetical interrogations, suddenly offers a self-portrait that seems precisely nothing less than “a hallucinating animal” or a humanimal hallucinating itself.

My next point would be about this entry from Bacon/Curieses:

[December 9th]

To think of painting as a mirror of the author or of the viewer is a superb stupidity. The canvas is only a mirror of the painting.

This entry wants to explode the comfortable cliché of the painting as mirror of the artist but is further complicated by the following entry:

[March 4th]

My obsession with the isolation of the individual and the cage finds another of its forms of expression in the glass which covers many of my canvases. They are separated from the viewer. However, through the reflection the glass produces, the viewer is transferred into the interior of the painting. Thus, the obsession is realised and the cage doubles.

We enter the fascinating problem of multiple nested reflections, Bacon painting and also using reproductions of earlier paintings as references and influences of the painting in progress. This all brought forcefully to mind one of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus, Sonnet 3 (Part II). If we compare and contrast three different translations of the sonnet (by Christopher Hawthorne; M.D. Herter Horton; and Robert Hunter) they seem to offer an eerie coincidence with Bacon’s idea of going into, through, being within the mirror, and analogous to the first statement,

the translated page is only a mirror of the translation process, not the translator.

Rainer Maria Rilke

Sonnets to Orpheus

Part II

Sonnet 3

Mirrors, no one yet has really described

what you are in your true nature.

You, as if filled with noting but the holes

of a sieve, the intervals of time.

You, spendthrift, still giving yourself away to the empty ballroom —

when the dark dawn comes, as wide as the forests,

and the chandelier goes, like a sixteen point stag

through your impossible gateway.

Sometimes you are full of paintings.

A few seem to have entered into you —

others you sent shyly past.

But the loveliest girl will remain until,

there to her withheld cheeks,

Narcissus, clear and set free, shall force his way.

Translation by Christopher Hawthorne

Sonnet 3

Mirrors: never yet has anyone described,

knowing, what you are really like.

You, interstices of time

filled as it were with nothing but sieveholes.

You, squanderers still of the empty hall — ,

when dusk comes one, wide as the woods . . .

And the luster goes like a sixteen pointer

through your impenetrability.

Sometimes you are full of painting.

A few seem to have gone into you — ,

others you sent shyly by.

But the loveliest will remain, until in yonder

to her withheld cheeks the clear

released Narcissus penetrates.

Translation by M.D. Herter Horton

Sonnet 3

Mirrors: to this day, no expertise can explain

the key to what you truly are;

filling the interstices of time’s plane

with mere holes as from a colander.

Spendthrifts of the vacant foyer —

wide as woods beneath twilight stars . . .

And the chandelier bounds like a sixteen-pointer

through your impenetrability.

Sometimes you are filled with canvases.

Some even seem absorbed into your depths —

other styles you timidly dismiss.

But the loveliest remains, until appears

Narcissus to press her chaste lips,

fully liberated and crystal clear.

Translation by Robert Hunter

Chandelier/luster; spendthrift/squanderer; individual choices in diction, but contrast “empty ballroom” with “empty hall” with “vacant foyer” and we visit different worlds: dancers departed or never invited; no king, no retainers; no visitors. Moving outward from those individual differences, each translation becomes increasingly unlike the others. An echoic triptych.

Layla Benitez-James: Thank you for pointing me towards that Borges, as well as the Rilke, that sentiment is so exact and those translations are all so different! It was a fun project to work on (and such a tangle to figure out which quotes/facts/people were really taken from Bacon’s life and which were invented) This is where the Disney bit is from, it’s real (and really hurt Bacon’s feelings). I am loving the Rilke, thinking about multiple nested reflections and about ¨nesting¨ as a poetic strategy, I can see Rilke operating like this at times, crafting images and concepts like Russian stacking dolls one inside of the other.

You know, initially I was thinking that our two works were so different, but slowly a kind of web may emerge where associative links are made to get from one to the other, a conversation that follows or revolves around the idea of “six degrees of separation,” or shrinking world where any two people or things are always connected, albeit sometimes distantly.

Already I was especially reminded of this poem by Tony Hoagland. “Lucky” has that same relationship in a more condensed flash that Bárcena teases out in his fiction. I think the typical way to describe this relationship is either with sadness or sentimentality and both authors are completely subverting this to get at this darker side of care.

The Borges brought up this quote from Don Quixote, I’m actually not sure whose translation this is, I’ll have to check to see if I’m also paraphrasing:

“Translating from one language to another, unless it is from Greek and Latin, the queens of all languages, is like looking at Flemish tapestries from the wrong side, for although the figures are visible, they are covered by threads that obscure them, and cannot be seen with the smoothness and color of the right side.”

With the Borges piece, as with Man in Blue, I think about the strength of the episodic and content dictating form rather than form dictating content. How does a reader interact with these pieces vs a speaker in a story like Bárcena’s who is so matter of fact? And with the Borges, does the last word go to the last paragraph´s word or the last word on the page, the last footnoted word? I feel like playing with form in this way allows a writer to “cheat” a bit in a good way and write two final words.

I’ve just gotten into Valeria Luiselli’s “Faces in the Crowd” which is so episodic but justified right at the beginning of the novel as the narrator has two small children so she has to write in short bursts. I’m wondering now about a writer’s need or desire to validate or explain the form to the reader, to justify it in some way. This kind of pleading or direct address is sneaky because it states its agenda so clearly, its honesty can be the disarming tool that draws you in. Bárcena’s narrator’s familiarity/direct tone does that for me: it is “Mom” instead of “my mother” so somehow I as the reader am pulled into this familiar world as a sibling or family member almost and that takes it beyond satire, the reader is really pulled around emotionally quite wildly. It makes me veer towards fiction writing craft talk in service of translation craft talk, like, the need for understanding the source text’s tricks and tools in order to make a good translation.

I really connected to your translator’s note breaking down the emotional resonance of Bárcena’s story, especially the description of “humans’ unenviable, Sisyphean labor to maintain clarity and make peace with the reality of corporeal decay and its attendant physical suffering” which gets so well at the hopelessness of a line like this: “We cry in silence for days gone by: for all our yesterdays, and for tomorrow as well,” but which wraps around to the meta/philosophy of the ending and the idea “that truth can be any lie properly told. After all, knowing that something was true never really did us much good anyway.” In some ways, good fiction is a lie properly told, or invented stories with “true” feeling. Part of Bacon’s justification for the “violence” in his art (both real Bacon and Curieses/Bacon, they too are now a bit tangled in my head…) was that it is a true reflection/mirror of life. Life is sad and violent and bearing witness to suicides/depressions/oppressive societal forces cannot just give way to flowers and sunshine…but that there should be some pleasure taken in truth telling and reflecting even the saddest facets of life.

Though in this current political climate and with ideas of “post-truth” swirling around the ending of “Good Intentions” is just a bit more sinister. Where I initially read only on a level of family, I begin to hold it up as a larger metaphor for how people are kept in control.

I did not know that Borges story before but I really enjoyed it! In the past, I have tried to describe the Man in Blue game as akin to Nabokov’s Pale Fire in terms of having a fictional scholar and footnotes, etc, that the scholar and translator of the text are kind of hidden characters who are present/not present throughout, but with Curieses I had yet to be able to really put my finger on why it’s different. That Borges piece finally offered me some clue; it is the lack of over the top personality/agenda that leads to them being more on the invisible side in Man in Blue. The Borges character has a clear agenda and such a strong/unsubtle way of trying to get his point across and, much like the scholar in Pale Fire, they are amusing to read especially for academics because we “know” these characters and it feels good to laugh at them a bit. But I’ve always thought of “Edward Cullen” as just this really earnest scholar trying hard to sound professional and perhaps young/this manuscript is his “big break” so just the barest bit of personality comes through, much like with the footnotes, almost seems like a younger person trying to sound like a grown up and get everything just right which is a much more understated way to play the use of that kind of framework, but I think it is because Curieses wanted it to disappear a bit (the lulling the reader into focusing on Bacon and letting things skate really close to real life).

BR: The Tony Hoagland poem is a startling cousin to Juan Gómez Bárcena’s story; edgy, angry, ultimately more overtly, less problematically compassionate, less Baconian. Powerful. It gives permission for the struggle, anger, and so, too, love between parents and children, even after many years of difficulty.

The Don Quixote quotation seems to be from Edith Grossman’s translation. I guess the question is, if you’re “seeing” the figures from the other side, are they really “visible”? Does it suggest that translation really only shows us the threads, i.e. the inner workings, the structure, that every translation is a kind of Pompidou Center with the traditionally concealed, traditionally unattractive “guts” on the outside? Is it the idea that the translation shows you the motor but doesn’t really let you ride in or drive the car?

LBJ: I love the idea of translation being like a kind of Pompidou Center. What a strange building that is, both lovely and aggressively unattractive in comparison to more classic and romantic architecture in that city. I feel like I might easily get obsessed with our metaphors for translation and for a while I was trying to reimagine William Carlos Williams´s idea that ¨A poem is a small (or large) machine made out of words¨ as it seemed to me that poems or stories were more like computer programs and that we human readers were the machines trying to make sense of them. In computer programming when you write bad code the system ¨returns errors¨ and it does not function; if the code is good, you make something appear as if by magic, you double click on a link and the screen blooms into a video or a story. It could be even truer for translations, even a good translation could return errors or leave you unmoved despite revealing the inner workings of that motor.

BR: Like Bacon’s paintings, Bárcena’s story is confrontational, like Harold Pinter’s The Homecoming bringing us to a brutal family reunion, or the next stop on the line one perceives from Buñuel’s Chien Andalou — serving up the sadism of nightmare and the nightmare of quotidian misogyny — to David Lynch who cruelly ratchets up the hysteria in the psychic rape scene between Lula Pace Fortune and Bobby Peru in “Wild at Heart.”

The reader is ushered into a very uncomfortable scene and challenged whether to, for example, be amused or horrified; either response is risky; to laugh is to embrace the narrator’s cruelty, to normalize their madness, or is it really just responding to the rhetorical irony? To lament is to, possibly, miss the point, an easy response, bringing sentimentality to a story that is, on another level, an exposé of domestic abuse. Another possible response is what you mention, about “some pleasure taken in truth telling and reflecting even the sad facets of life” and in that way the story authorizes us to laugh and cry as part and parcel of the same realization. Catharsis. Can Bacon be cathartic, too? His paintings do seem tragic illustrations.

These fraught relationships, of mother and son (if it is a son in Bárcena’s story) propel me to a beloved holiday story, Truman Capote’s masterpiece, “A Christmas Memory,” a touching story told by an adult narrator thinking back to his poor childhood, when he was called Buddy, spent in the company of an old cousin; he is 7, she is 66. And she is somewhat simple and he is her confidant and ally in a household of other, unfriendly relatives. Their tale seems the good dream to Bárcena’s nightmare.

When Buddy catalogues all the modern things his cousin has never done, and then all the things she does, what comes to mind is the list in a story by another Southern writer, Flannery O’Conner, the story being “A Good Man is Hard to Find” (1953) when the murderous Misfit describes all the things he’s been in his life. These are portraits.

Here is The Misfit (O’Conner):

“I was a gospel singer for a while,” The Misfit said. “I been most everything. Been in the armed service, both land and sea, at home and abroad, been twice married, been an undertaker, been with the railroads, plowed Mother Earth, been in a tornado, seen a man burnt alive once,” and he looked up at the children’s mother and the little girl who were sitting close together, their faces white and their eyes glassy; “I even seen a woman flogged,” he said.

Here is Buddy (Capote):

“In addition to never having seen a movie, she has never: eaten in a restaurant, traveled more than five miles from home, received or sent a telegram, read anything except funny papers and the Bible, worn cosmetics, cursed, wished someone harm, told a lie on purpose, let a hungry dog go hungry. Here are a few things she has done, does do: killed with a hoe the biggest rattlesnake ever seen in this county (sixteen rattles), dip snuff (secretly), tame hummingbirds (just try it) till they balance on her finger, tell ghost stories (we both believe in ghosts) so tingling they chill you in July, talk to herself, take walks in the rain, grow the prettiest japonicas in town, know the recipe for every sort of oldtime Indian cure, including a magical wart remover.”

Both catalogues depict these characters in a transcendent, metamorphic light, not bound by modernity. O’Conner’s has the same frightening depiction of misogyny and an almost total lack of male-female understanding we could find in Faulkner, in Popeye’s rape of Temple Drake in Sanctuary, and, conversely, in As I Lay Dying, Addie’s hatred of Anse, and men in general, for impregnating women and stealing their freedom. Bacon, too, is both utterly modern and temporally transcendent; his figures seem both crushed and bound within the frame even while streaking or speeding out of it. Both stories present unusual, male-female, parent-child dynamics. In O’Conner’s story, the grandmother who has an antagonistic relationship with her own son and his wife and children, tries to sweet-talk the Misfit out of murdering them all by suddenly pretending to be the mother-figure he never had. This only earns her getting shot by the Misfit “three times through the chest.”

LBJ: Yes! I had not thought of catalogues and listing in that way before but they definitely get at the heart of trying to be understood, that strategy is itself a kind of messy architectural jumble. I was taken with a passage from Lloyd L. Brown’s 1951 novel, Iron City, which was operating in this spirit:

A thousand men on fifty ranges were standing and waiting — the young and the old, the crippled and whole, the tried-and-found-guilty and the yet-to-be-tried: the F&B’s, the A&B’s, the drunk-and-disorderlies, rapists, riflers, tinhorns, triflers, swindlers, bindlers, peepers, punks, tipsters, hipsters, snatchers, pimps, unlawful disclosers, indecent exposers, delayed marriage, lascivious carriage, unlicensed selling, fortune telling, sex perversion, unlawful conversion, dips, dopes, dandlers, deceivers, buggers, huggers, writers, receivers, larceny, arsony, forgery, jobbery, felonious assault, trespassing, robbery, shooting, looting, gambling, shilling, drinking, winking, rambling, killing, wife-beating, breaking in, tax-cheating, making gin, Mann Act, woman-act, being-black-and-talking-back, and conspiring to overthrow the government of the Commonwealth by force and violence.

This novel too played with skating close to reality and was described in terms of its “documentary and testimonial qualities,” blurring the line between art and reality because Brown kept folding in real events from his time in jail. Thinking of Bacon´s paintings and Bárcena’s care in description I am reminded too of Robert Pinsky´s essay, “American Poetry and American Life,” from Poetry and the World. Pinsky´s talking about the James Wright poem, “Autumn Begins in Martins Ferry, Ohio” and he says¨: “Wright’s poem is a meditation on what he has to celebrate, or on the relation between the celebration of poetry and the available glory in American life.” That phrase, ¨available glory¨ has always stuck with me, like, even in these harsh scenes that directors or artists sometimes draw out, or these catalogues that seem to reduce humanity to these base components or labels are still reaching for something noble.

I’ve just started reading again Roland Glasser´s translation of Fiston Mwanza Mujila´s Tram 83 and he leaps into a similar list right in the first few pages:

Inadvertent musicians and elderly prostitutes and prestidigitators and Pentecostal preachers and students resembling mechanics and doctors conducting diagnoses in nightclubs and young journalists already retired and transvestites and second-foot shoe peddlers and porn film fans and highwaymen and pimps and disbarred lawyers and casual laborers and former transsexuals and polka dancers and pirates of the high seas and seekers of political asylum and organized fraudsters and archeologists…

He just goes on and on and it is wonderful to see a kind of joy and playfulness woven through a description of a harsh environment, it is giving this crucial background and yet a game is being played at the same time.

BR: These catalogues of identity suggest that we are what we do or do not do, action or absence thereof (to be is to do, to do is to be), and the idea that one can be and do many things but of course lists are always selective, partial — in both senses. This returns to the problematic nature of the translator’s performative craft, continuously forced to select from multiple ways of rendering a single sentence. Like the numerous, aforementioned touchstones, subjective associations and objective correlatives, the translator walks the same tightrope between denotative boundaries and alluring connotative cloud castles. When this obligation is multiplied across the pages of a story or a whole book, like it or not, the resultant translation is nothing less than a simulacra, an abstraction of the original, and, hopefully, for both author’s and translator’s sakes, a holistic artifact on its own terms. Which makes the translator a kind of phantom alchemist.

Capote’s and O’Conner’s catalogues are artful delimitations, selective signifiers, not full-dress portraits; also Capote’s list is the adult Buddy remembering his older cousin many years after the fact while the Misfit’s list is his own lyrical litany, a self-portrait; and like the list in Curieses’ novel about the accoutrements of Bacon’s studio (a nightmarish habitation as evidenced by photos of it, and suggestive of the crazed screaming lonely house in Bárcena’s tale), that mass of detritus suggests tremendous energy and violence, both facts of Bacon’s canvases, but violence doesn’t tell Bacon’s whole story, especially when Curieses writes about how Bacon so carefully stage-managed and curated his interviews; a more subtle manipulation. Both Bacon’s studio and the locked house-prison in “Good Intentions” are portals, keyholes, through which the world is measured and rendered through a very peculiar prism. True, too, in Borges’ story “The Aleph,” about which Carlos Fuentes writes:

The Aleph is the space which contains all others but which does not depend on a minute and detailed description of all the places in space; it is only visible simultaneously, in a gigantic instant: all the spaces of the Aleph occupy the same point, “without overlap and without transparency”: “each thing was infinite things…because I saw it clearly from every point in the universe. I saw the swarming sea, saw the dawn and dusk, saw the multitudes of America, saw a silver spiderweb in the very center of a black pyramid, I saw a cracked and broken labyrinth (it was London)… I saw all the mirrors on the planet and none of them reflected me…”

The irony of this vision is double. On one hand, Borges must enumerate what he saw with simultaneity because a vision can be simultaneous, but his writing must be successive, because that is the nature of language. On the other hand, this space of all spaces, once seen, is totally useless unless it contains a personal history.

(Carlos Fuentes, The Great Latin American Novel, trans. Brendan Riley)

Bacon seems to be after something similar; his portraits have the look of time frozen, action suspended, an attempt at encapsulation in order to reveal a truth that might otherwise be lost; a “terrible beauty,” not Yeats’ revolution but a personal struggle against the demands of representation, something which Francisco Goya wrote about in a 1792 report to the Academy of San Fernando, which Robert Hughes quotes in his biography of the painter, and deems “one of the few expressions of theory this supremely untheoretical painter ever allowed himself”:

“[T]here are no rules in painting, and . . . the oppression, or servile obligation, of making all study or follow the same path is a great impediment for the Young who profess this very difficult art that approaches the divine more than any other.”

This also touches, Layla, on your pondering the nature of last words. If there are no rules in painting, i.e. art itself, then there is no last word on meaning. So many stories beg this question, the open-closed circle, a completed story; it’s the unreliable narrator problem, the Rashoman syndrome, what Julio Cortázar’s Hopscotch is all about.

LBJ: A novel I still need to read! Along with looking forward to reading The Great Latin American Novel which I have been reading about. I love experimental work (even though that term is so slippery) especially because it forces you to question concepts like a last word or the order in which you absorb information as a reader, especially with something like footnotes. Or especially when we begin to think about utility vs art and where those ideas get tangled in theory, what makes a completed story.

While I’m comfortable with the idea that the author, for all their constructing, won’t walk away with complete control over their story once it is read and takes up a life of its own in people’s minds, extending that idea out to the work of translators makes me wonder about “we are what we do or do not do” and those actions taken and not taken defining us.

With these specific titles and descriptions translating across languages and cultures I’m not feeling those places to be particularly prone to being backwards Pompidou tapestries. We can step back and accept that there are no rules or that the narrators are simply unreliable but then trying to pick those circles apart to translate can also bog me down in philosophy so that the words end up inching by on the page…gives more weight to the idea of constructing a character taking time akin to constructing a building.

BR: So we make life and life is what we make it, and make of it. More concretely, Bacon’s paintings are wild and alive, they illustrate the problem Shakespeare explores in Macbeth when words fail because the world, humans, are so horrible to one another, so Macduff declares as he begins his battle with Macbeth: “I have no words: My voice is in my sword: thou bloodier villain Than terms can give thee out!”

The artist is disenchanted but refuses to give up on mankind; instead the artist will resolutely offer yet another reflection, however horrible. And we place Bacon in the nightmare traditions of Goya, Fusselli, Munch, and, given the deliberate, deconstructed horror of Bacon’s canvases, a writer like William S. Burroughs, whose ouevre is an elaborate, highly visual, cinematic politics of outrage: the gangle-mare conjured up in the opening pages of Chapter 8: “I Sekuin” from The Soft Machine is a very deliberate and effective rendering of the author’s desire to provoke unease vis-a-vis translating near-unspeakable emotions and images into the reader’s consciousness and onto their conscience.

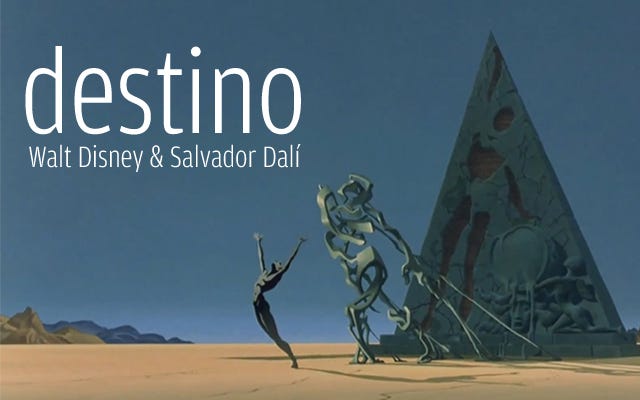

Considered this way, Francis Bacon’s art is not quite comparable to that of Walt Disney, whose general vision is a lucrative lozenge, commercial pacifier (prompted by him painted by others); but when we bring Dalí into the mix by touching on his collaboration with Disney, their beautiful 1945 cartoon called “Destino,” there’s something of Bacon there, too.

Even with its beautiful Fantasia-like pastel animation, “Destino” is concerned with what appears in Bacon’s paintings, an obsession of Dalí especially, seen famously in “The Persistence of Memory,” that is, the decay of time; there are some faces in this cartoon which approach the grotesque decay we see in Bacon. “Destino” also incorporates the medusa, the menacing voyeur, the young beauty horrified by a vision of the crone she’ll become.

Apparently, Dalí described the cartoon as “A magical display of the problem of life in the labyrinth of time,” while Disney opted to claim, less philosophically, more romantically, it was “A simple story about a young girl in search of true love.” It’s funny how much the two, at least in photos from the time, resemble one another. In this way both try to justify form and content. We can also think of how James Joyce elides the problem entirely in Finnegans Wake, not only with surreal dreamscape language (Dalí, Disney, Bacon) but also by leaving it up to the reader:

“the curious warning sign before our protoparent’s ipsissima verba (a very pure nondescript, by the way, sometimes a palmtailed otter, more often the arbutus fruitflowerleaf of the cainapple) which paleographers call a leak in the thatch or the Aranman ingperwhis through the hole of his hat, indicating that the words which follow may be taken in any order desired,” (Joyce,bold-face type, mine).

LBJ: I never knew of this Dalí and Disney collaboration but it is lovely and wonderful how different their takes are, and fitting. I’m thinking now of Dalí doing commercials in the US and how surprising that was for me to discover as I had placed him on this strange surreal pedestal that somehow eschewed the concept of art being commercial. From what I have read of Bacon and Curieses’s take on his personality he also had conflicting thoughts where money and art overlapped. So often the quotes/conversations seemed to turn to the hyperbolic or absurd when the artist perhaps failed to make up their own mind. I like the idea of the reader or consumer taking their words (or last words) in whatever way they desire but then again I feel the consumer/spectator also demands to be directed, we want to be lead and instructed on how to view an art piece, to have these giant blocks of text painted onto the walls of museums to give context and, depending on the reader, ample biographies and footnotes. Even as I romanticize experimental works I do want some order, I want to be able to “figure out” the game or be “in on” the joke, want both the wonder of the magic trick and to have it explained.

BR: And Cortázar does this, too, in Hopscotch, an open-ended, hypertext novel that, in its own words, “consists of many books” and invites multiple readings. The “first book” permits one to ignore everything beyond Chapter 56 “with a clean conscience.” This means reading the novel’s first two sections “From the Other Side” and “From This Side”, but not the third, “From Diverse Sides — Expendable Chapters.” Expendable means 40% of the pages are left unturned; 99 chapters unread! How should the reader take the author’s “instructions”?

Like the Misfit, like Buddy’s old cousin, we don’t really get to tell our own story; that’s the problem in Pale Fire, too. Who has more power, the poet or the critic, the painter or the curator? Both have different kinds of power. Even such provocative portraits as Bacon’s may not tell the whole story. And so back to translation.

The translator is empowered by the source text; their translation may be authorized, so they may be helping to normalize and authorize the author in the target language, or if not authorized may add scandal to the conversation, an act of theft; is an authorized translation an authorized theft, possibly a grotesque pantomime?

Bacon’s portraits defy expectations, as does Finnegans Wake, as does Hopscotch; the painterly portrait shows more than the subject; just as Goya did not flinch from depicting atrocities in his Disasters of War — translating them, for visual depictions are of course translations, from his own experience of visiting battlefields — neither did he sanitize his portraits. As Carlos Fuentes writes in The Buried Mirror: “Goya could get away with murder — figuratively, as he painted the court of Charles IV and the royal family without softening their asinine features.” I cannot help but think of Bacon’s portrait which do not spare the viewer but instead incite a kind of fascinated hysteria.

Bacon’s portraits make me think of Sylvia Plath’s metaphor for honeybees in flight “outriders, on their hysterical elastics” from her poem “The Bee Meeting”:

Smoke rolls and scarves in the grove.

The mind of the hive thinks this is the end of everything.

Here they come, the outriders, on their hysterical elastics.

If I stand very still, they will think I am cow-parsley,

A gullible head untouched by their animosity,

Not even nodding, a personage in a hedgerow.

This poem presents another parent-child conundrum. Like Plath’s four other “Bee Poems,” it deals with her anxious, oppressive, sometimes nightmarish relationship with her father (most trenchantly inscribed in “Daddy”). In “The Bee Meeting,” in order to survive, the poet must translate herself back into nature, into some essentially inanimate object, in order to escape detection, in order to avoid being stung; it’s a portrait of the artist trying to survive. Bacon’s portraits look like what Beckett writes about, people crushed under life’s wheel.

LBJ: Well and Beckett reappears at the end of the novel, their fates are wound even more closely together and the surreal aspects of Bacon’s life jump out and literally almost crush him to death, the metaphors become real, if only in dreamtime. This will perhaps throw the tangent out further but the very physical representation of that kind of metaphorical threat reminds me of Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s “The Dragon” as there is this kind of insistence about the surreal reality… While the images are wild, the emotional register is intense and direct, the danger is both metaphorical and real, or resists being solely metaphor.

But to get away with murder — figuratively…at certain times and in certain political climates there is a real blurring of what is safe to write and how it is safe to construct your work (and yes! who is allowed to translate and where and in what context!) I think about provocation and the bravery of some artists to risk real physical danger in order to represent their reality, or to risk failure and ruin, to survive years or long periods of rejection without ceasing or worse. I think there is a kind of catharsis or satisfaction one can get from writing out of difficulty or tragedy, but at the same time there is that risk of being labeled or misunderstood in certain ways, perhaps part of rejecting the rules as an artist is to have a kind of faith in time and that art surviving whatever crushing forces come along.

BR: In Bárcena’s story, to survive the unhappy past that has become a nightmarish present, the narrator must become the mother, reinventing, replaying past cruelties in new ways that are an even worse mockery of the family and, by the understanding they necessarily engender, they bring about a horrible catharsis.

As if the pressure involved in depiction, in translation were not enough, as you mention, moments of “post-truth,” and even, pray not, “post-literacy,” may be shambling our way, but I’m also encouraged by a moment in Capote’s tale, when Buddy and his cousin go to buy whiskey for making fruitcakes at the café of the fearsome Mr. Haha whom they’ve never seen and who, while he is grim at first, turns out to be good-humored and generous. Buddy and his cousin translate their love of people and good things into thirty-one fruitcakes to be given away as Christmas gifts to people whom they hardly know. About his cousin, Buddy wonders: “Is it because my friend is shy with everyone except strangers that these strangers, and merest acquaintances, seem to us our truest friends? I think yes.”

And yet, it’s the seemingly cruel adults who burst in on Buddy and his cousin’s whiskey revelry with angry voices, and those momentary ugly portraits catalyze their love for one another. Like Borges’ disquieting glimpse of eternity in “The Aleph,” the electric gravity of Bacon’s portraits invite us to stare into the distorted void we excavate and be heartened by the fact that we can stand it.

And like ardent fans of celebrities who captivate them so much they feel that they know them, I think we translators have a similar voyeuristic relationship with the authors whose work we render into a tongue foreign to the original. We feel drawn to the original, as if to a portrait, or a painting, one we’d like to have painted ourselves, in this case a poem or book, and when the symbiosis works well, when the book or story is vital and beautiful, when we feel we must be the one to reveal it, to crack its code, we are enlivened by the act of translation and bring something new to life. Like portrait painters, we translators create complex shibboleths.

Between Us: Translators in Conversation was originally published in DrunkenBoat on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.