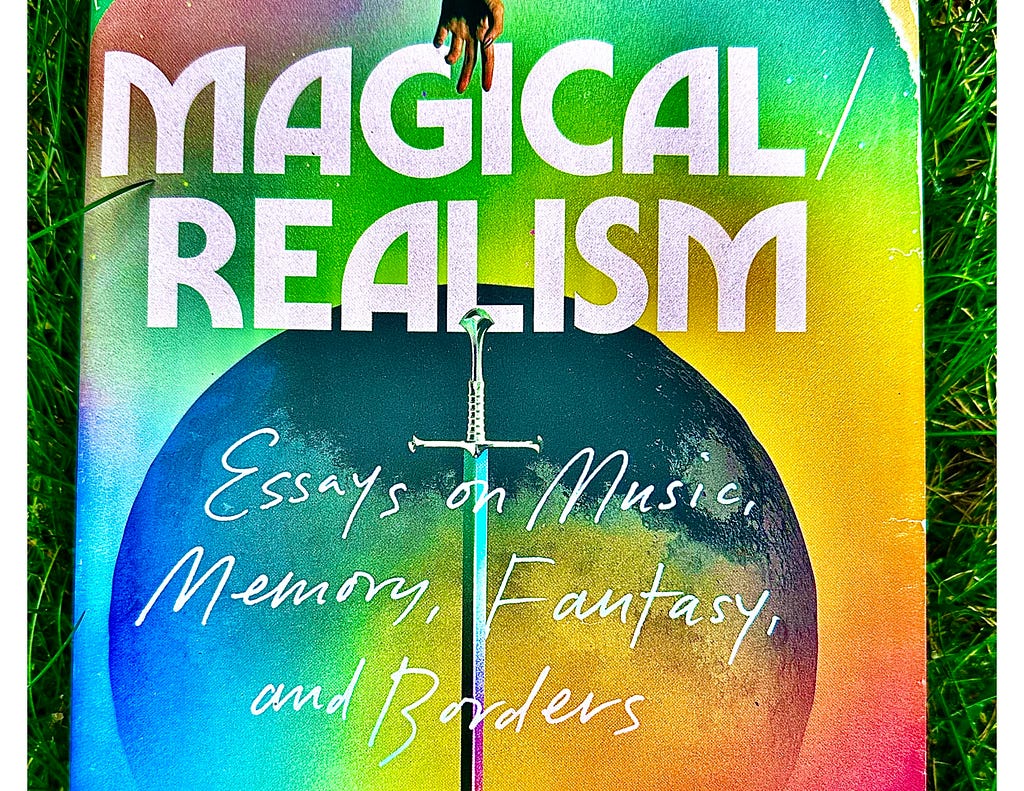

Magical / Realism is a collection of personal essays about pop culture, identity, identity formation, border history, linguistics, literary theory, and immigration. Tiny Rep Books, an Imprimatur of Penguin Random House, published it in May of 2024. In Magical / Realism Villarreal creates for the reader two things: 1) a chronological narrative as a Texas-raised child of undocumented Mexican immigrants, and 2) a critical assessment of immigrant narratives by uncovering many of the complexities of what it means to grow up in the United States isolated from deep familial and cultural history. Villarreal’s imagination spans the Texas / Mexico border story — however atypical — and her essays reflect the experiences of immigrants who’ve grown up far from any geographical border or on the margin of a central immigrant narrative.

I first came to know Villarreal’s work in her book of poems Beast Meridian, published by Noemi Press in 2017 as part of their Akrílica Series, a cooperation between Letras Latinas at the Institute for Latino Studies at the University of Notre Dame and Noemi Press. I love Beast Meridian for its willful experimentality, raw honesty, and attention to craft. Having immigrated from Peru when I was very young to Southwestern Michigan with my parents, I felt connected to many aspects of this book.

I came to admire and enjoy Villarreal’s online presence, too, when I found it a few years later. During the first months of the COVID pandemic lockdown, the parasocial took on more power and Villarreal’s voice in all the mediums sustains an honest clarity. Through her online posts I’d read a few of the essays in Magical / Realism previously in The Cut and Harper’s Bazaar. I’m a fan of video games and sci-fi epic series, and I care about how gender and race are performed, oppressed, or erased, in popular media. So Villarreal’s subjects automatically attract me. As an avid reader of poetry, and pop-culture engaged gen-Xer, I was all set up to fall for Magical / Realism. I tried hard to resist.

One of the earliest things you learn in graduate school is to effectively depersonalize your relationship to the text. This allows, they say, an objective critical reading. So when I first read Magical / Realism I thought I’d give this depersonalization schtick a shot, and I began by breaking down the organizational scheme. Villarreal organizes 19 longer (about 7 to 30 pages) and 11 shorter (about 1 to 4 pages) essays into a roughly chronological order based on the topic or time of writing.

The longer essays are all written from the first-person POV (as expected from personal nonfiction) and Villarreal often uses various kinds of braiding or interweaving of subjects to explore the interplay. These essays combine personal history with cultural/gender/racial power dynamics, theory, and pop-culture. Some begin with the personal, like “My Boyfriend’s Maid: a Reverse Cinderella Story,” “La Canción de la Nena,” or “Memory: a Lacuna,” before weaving in theory or pop-culture. Others begin with pop-culture or theory, like “All the Atreyus at the Sphinx Gate” or “The Fantasy of Healing,” or “When We All Loved a Show about a Wall,” and weave in the personal.

The short essays occupy two categories: “Encyclopedia of All the Daughters I Couldn’t Be” and “Magical Realism.” Villarreal uses second person in some of the “Encyclopedia of All the Daughters I Couldn’t Be” essays, and titles them “Buen Niña,” “Bonita,” “Doctora” or another version of the ideal daughter the author feels she didn’t — or hasn’t yet — lived up to in the eyes of her family. All of these appear in the first half of the book. Formatted like newspaper articles — two columns per page — Villarreal’s formative memories are presented as reportage best communicated with a journalist’s relative objectivity. The three “Magical Realism” essays in the second half of the book explore a different space. These appear in sans-serif font, mostly, distinguishing them from the serif used everywhere else, and explore themes of bifurcation in the author’s adulthood: between people, between family, between cultures and geographies.

I read the book front to back, but you can read the essays in any order, many of them short enough to be read during stopovers between flights, or while waiting to air dry after a shower. Others require three cups of tea, a snack, and walk around the block to help you process the implications. After reading the table of contents, counting pages, and noting formatting and thematic relationships, I had a HUD guidance system to assist me with the play through. But did it help quell my burgeoning appreciation? Nope. Not one bit.

Everything in Magical / Realism is a pleasure to read. Villarreal’s stylistic choices help the author reach a wider audience, one more comfortable with clearer modes of address. Given the formal experimentation of her poetics, this is admirable. Sometimes the clear rhetoric gets managed through episodic associative structures, like in “En Útero” and “Volver, Volver.” Other times it’s narrative that carries the reader through the argument. Both work, and both offer different rewards.

Sometimes it’s as if her essays collapse in on themselves. Many of the “Magical Realism” and “Encyclopedia of All the Daughters I Couldn’t Be” short essays function that way, like dying stars turning into black holes, incredibly dense with meaning. I sense unresolved pain and regret in the short essays. Each opened a tiny window in a different doorway.

In many of the longer essays Villarreal explores pain, grief, and anger, but after longer explorations across multiple spheres, they’ll end with moments of resolution, even hope and optimism. In “After the World-Breaking — World Building,” she writes:

My writing is illegible to American audiences, no matter how much I love Star Wars or Michael Jackson, or The Great Gatsby; in return, my life is invisible, unintelligible to the only culture I know. Despite our exclusion from mainstream media, immigrant Latines identify with tv shows, films and music that have never had us in mind…. We learn American culture inside and out, learn to speak its intricate languages, but are rarely entrusted or imagined, in its stories…. By relieving our ghosts of the burden of their stories through fabulation, we are liberated to imagine the fantasy of possible futures.

Grounded in lived experience and supported with theory and the art of language, these essays display Villarreal’s ability to make unique connections. Sometimes it seems as if the longer essays will never stop expanding. But they still manage to come together in a satisfying completeness. “En Útero,” especially, has that quality. Initially about the poles of Villarreal’s adolescent musical awakening (Selena and Kurt Cobain) during a difficult era, the essay ends with the most touching, bittersweet friendship with Calliope, Editor-in-Chief of their high school literary magazine. (Calliope — can’t help but wonder if that’s her real name.) “Volver, Volver,” also expands — literally. A reimagining of an essay written eight years earlier, the text of the original essay (about 5 to 10 % of the final essay in the book) appears in bold, with the later additions in regular text. It’s not necessarily a challenging read, but it does challenge the reader. You’re meant to understand the limits of the previous essay, while also perceiving the limits of the younger author.

These kinds of formal experiments reveal in Villarreal a strong, active mind, one that cannot quit until the truth has been revealed. In the five weighty essays leading up to the afterword, we read Villarreal’s glosses on current media: video games as tools of healing (“The Fantasy of Healing”); white supremacy as played out in media via Norse mythology (“In the Shadow of the Wolf”); AI, linguistics, poetry, cultural memory and digital labor’s dehumanizing force (“The Final Boss”); colonialism, space operas, epic fantasy, and the apocalyptic narrative (“The Uses of Fantasy”); and politics, race, and empire in Game of Thrones (“When We All Loved a Show about a Wall”). It’s a wide-ranging list, right? Some passages are a lot to chew on, if you haven’t played the video game, but forcing down the meal has its rewards. It seems like everyone and everything gets at least a mention: Jon Snow, Susan Sontag, George Lucas, Beyoncé, Carmen Maria Machado, Joseph Arthur Gobinaeu, Odin, Saidiya Hartman, Schrodinger’s Cat, Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla, Jacques Derrida, bell hooks, Vicente Fernández, Thoth, Los Tigres del Norte, Viet Nguyen, Bruno Bettelheim, GTA, Percy Bysshe Shelly, and Kathleen Hanna, among many, many others. All of these subjects read as personal to the author because they all tie in, in one way or another, to her most passionate subject (besides poetry and language): the right of the subaltern not just to survive, but thrive.

Magical / Realism captures many facets of Villarreal’s complex personal life. And yet, as deeply as those lived facets affect me (an immigrant with his own complex life) her creative and intellectual mind moves to the forefront in the second half of the book. She weaves the personal with social criticism in a way that feels earned, and knows what it means to be told by the wider culture that they’re not welcome. It’s also good to hear that wider culture called out. A passage from the last short “Magical Realism” essay captures Villarreal’s goals as a craftsperson, poet, artist, and critic: “I want to bring the wolf out of language and give the world back to it. Because if we’ve given the world back to the wolf, then we’ve already begun to repair the wound. . . .” Throughout the book her anger at the inequities of the world rises through the ink. More than once, we’re encouraged to see fantasy, storytelling, and fables as the foundational bedrock on which all cultures exist, and that language is the particulate of that bedrock. This book should convince anyone that it’s 100% true.

In her most emotionally open moments, Villarreal’s skills pay off on the promise of the book cover praise. The afterword unpacks her obsession with fantasy — especially the character of Jon Snow in Game of Thrones — and reframes her spiritual reliance on tarot and astrology during and after her divorce. While writing about dissolving the illusion of intellect as the tool to find safety and predictability, she comes to the knowledge that

…it’s been about reintegrating a deeply and historically fractured self through intuition, restorying, fabulation, ancestral communion, ritual…. Magical realism is of the heart; how the heart sees the world…. Is seeing what the heart believes possible in the real world even after it’s broken. Maybe even especially then.

I tried to resist the many seductive elements of Magical / Realism (to be honest, I didn’t resist that hard), but I’m a bigger fan now of Vanessa Angélica Villarreal’s than I was before. In some ways, it felt like it was written for me. But it wasn’t. It was written so that Villarreal could work her way out of a time in her life when the fabric of the world felt like it was disintegrating around her, consuming who she thought she was and was supposed to become. One of the “Encyclopedia of All the Daughters I Couldn’t Be” is subtitled “Intelligente,” and (probably because I’ve always felt like an impostor) that one hurt the most. Even in the afterword, after more than 300 pages of creative and intellectual excellence, she still confesses her imposter syndrome, an honesty I can understand. And I guess this is what I most admire about Villarreal. She wrote her way out of an emotional and psychic catastrophe, and recorded the clear evidence of her brilliance. Which is a lesson for us all (especially the writers): we can write our way out of pain and doubt, and arrive in a space where the real and the magic can be the same beautiful thing.

The Magirreal: A Review of Magical / Realism by Vanessa Angélica Villarreal was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.