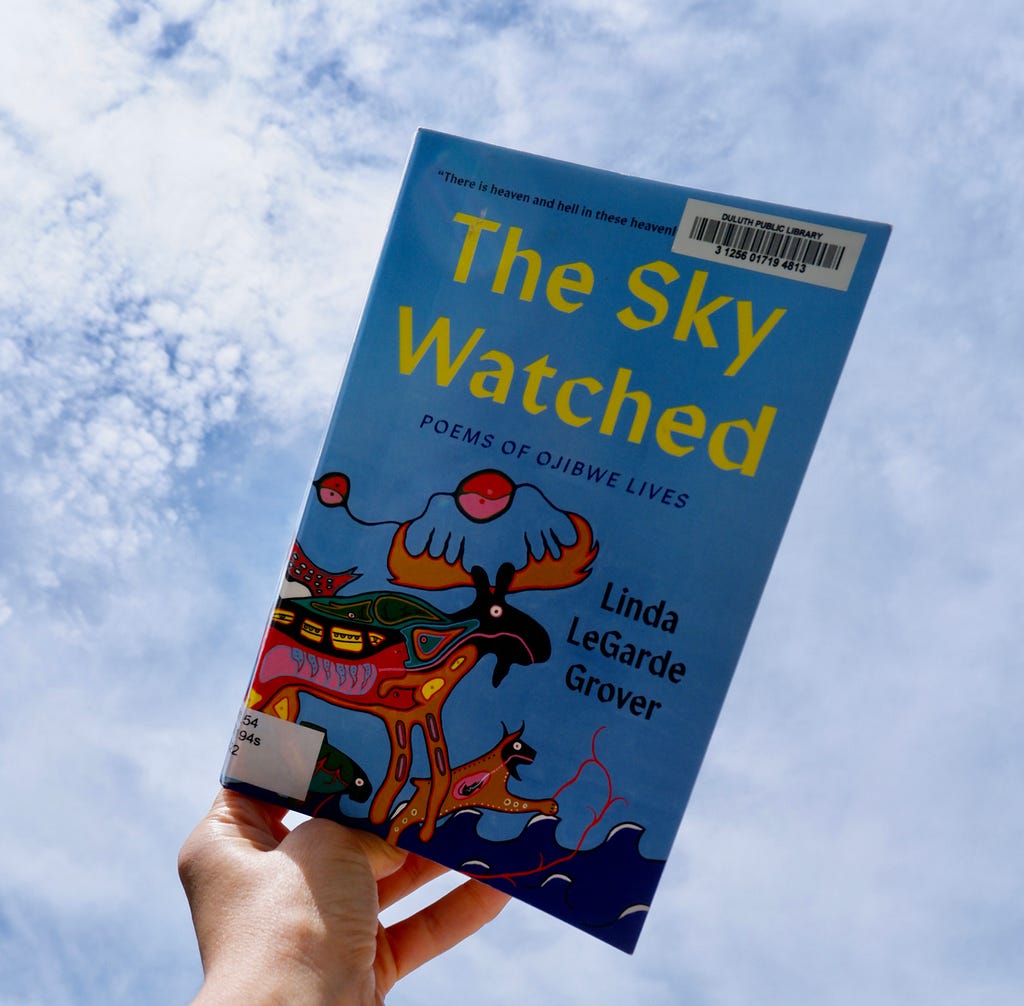

I was absolutely spellbound by Linda LeGarde Grover’s recently reissued and expanded collection The Sky Watched: Poems of Ojibwe Lives (University of Minnesota Press, 2016 and 2022). Organized in four parts, the collection examines four categories of Ojibwe culture, history, and daily life. If you’re not fluent in Ojibwe, make sure to have the Ojibwe People’s Dictionary handy to fully immerse yourself in the richly bilingual universe of these poems.

The collection opens with the storyteller tradition, evoking a timeless mythic world by rendering several key Ojibwe tales and teachings in dreamy poetry. In these poems, animals and natural elements exude agency and sovereignty, and the environment radically influences the trajectory of the people who live on the land. One poem depicts the story of Wazhashk (Muskrat), who saves the world after the great flood by “plunging / with odd grace and dreadful fragility / into translucent black water.” One poem depicts the daily journey of Gichigami’s sea-smoke spirits, first “curled in sleep” beneath the lake’s “frozen vastness,” then awakening with “delicate inhalations / from the sliver of space between ice and lake.” And in a poem that interweaves historical circumstances with wendigo legend, a community must flee a devastating forest blaze after “a piece of fire fell from the sky / […] [and] began to eat the earth.” When one woman’s child perishes during the migration, her “ravenous” grief stokes an “endless appetite” for wandering in search of her daughter’s spirit.

Section two is powerful and haunting in its examination of the boarding school era’s destructive impact. The vivid, intimate persona poems of this section are delivered from the perspective of various characters who survived this torturous institution. This terrifying world becomes palpable through Grover’s pen: the brutal erasure of “the language of your grandparents” and the exhortation to “speak English”; the shorn hair; the skin and clothing and bedsheets “bleached / immaculate” to conform to racist hygiene stereotypes; the enforced Christianity that trains students against “willful wickedness”; and the excruciating punishments — from kneeling on dried beans to being “lock[ed] […] in the basement” — administered for disobeying any of these directives.

In sections three and four, the storyteller-poet brings her acts of witnessing and honoring into the modern era. Taking place from the mid-twentieth century onward, these sections depict individuals in a close-knit community against the broader context of historical trauma and healing. These present-day speakers wrestle with the ongoing effects of settler colonialism in various ways. In one poem, an exasperated speaker wonders “How many of these / land acknowledgement statements / that are in truth / land acquisition statements / have I listened to, / […] delivered earnestly righteously / or crowing perhaps / with a triumphantly virtuous / preening of feathers.”

The cumulative effect of these poems is a generous, loving ethnography that radiates in concentric circles, from the poet to her family members to her community to several generations of ancestors, and all the way back to Nokomis and Nanaboozhoo. Uttering miigwech upon miigwech, these poems travel through many lives and many landscapes, but always come back to the fundamental principle of Ojibwe epistemology: gratitude.

Miigwech Upon Miigwech: A Review of Linda LeGarde Grover’s <The Sky Watched> was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.