You think you know someone. Then you see them in a different place, a different context, or after an absence of many years. They’ve changed; this version is unfamiliar to you. You can’t reconcile their speech and mannerisms with the person you knew before or elsewhere. Could this mean you never really knew them at all?

An interrelated set of dilemmas sits at the heart of I Think I Know You, Julie Gard’s new collection of prose poems (FutureCycle Press, 2023). People change over time. They change depending on circumstances. A specific environment can activate another side of someone. We try to know one another, we try to understand each other’s personalities and motivations. And while we fumble and strive for genuine connections, a fundamental barrier of unknowability hovers between us all.

Gard’s poems pinpoint communication — especially verbal communication — as the primary mechanism by which we try (and fail) to know one another. The speaker is highly attuned to acts of linguistic outreach and modes of semantic interaction, across time, space, and species. But she discovers that communication is always faulty or inadequate. “Twenty-three birds are speaking eight different languages in the forest behind me,” the speaker states. She appreciates how passed-down heirlooms allow “one era of history [to] be layered with another,” while admitting that when “ancestors knock on glass” or “[g]hosts speak” we only “imagine the words we are dying to hear” rather than achieving an accurate understanding of the messages. Several poems interweave snatches of dialogue from overheard conversations, and this found-poem technique emphasizes the collection’s sense of being surrounded by language all the time and yet estranged from coherent communication. In a particularly cogent analogy, the speaker watches a murmuration of starlings merge and divide in their classic unified formation, implying a wish for humans to be able to communicate with a “shared and magic brain” just as the starlings do.

Many of the poems specifically explore how places, both familiar and foreign, challenge our ability to communicate and influence our sense of knowingness. Russia, where the speaker lives for an extended period of time, makes her feel “faceless” as she grasps for “my vocabulary in your language.” She gradually becomes “a new person in a new place,” transforming from an ingénue into a streetwise local. But after returning to the States, the speaker wrestles with a newfound alienation from her childhood home and hometown — the place she ostensibly knows best of all — feeling like “I grew up part stranger […] in this place that I must be from.”

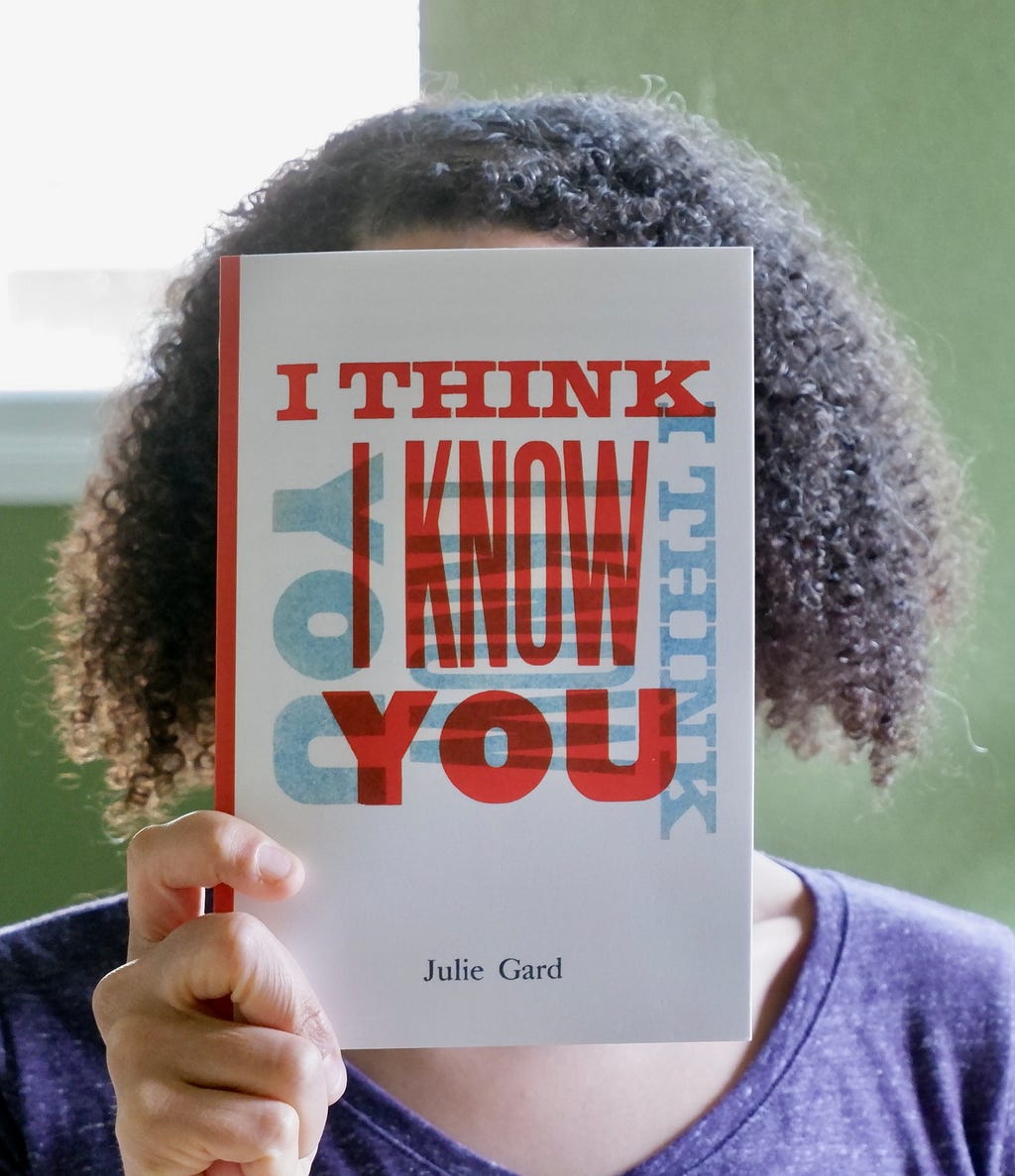

These geographical forays help the collection travel thematically between interpersonal communication failures and a broader commentary on sociopolitical turmoil. The collection’s most ambitious piece, a long poem titled “Election Season,” is set during the 2016 U.S. presidential election season, and chronicles the speaker’s growing realization that her countrymen, her neighbors, and even her family members aren’t the people she thought she knew. The book’s cover, with its bold red and blue lettering (a custom design by Duluth’s own Warrior Printress letterpress outfit), also hearkens to the utter breakdown of effective communication that has characterized U.S. public life for the past decade. On the cover, the duplicated phrases say the same thing but are arranged at cross purposes, obscuring one another, talking over each other instead of engaging in clear dialogue. It’s a cleverly devastating illustration of the book’s themes.

The speaker ultimately finds enduring value in domesticity, in the comforting routines of her household. The objects with which she interacts, and the daily rituals she performs, create safety and stability. It’s the “wooden fence posts” and the “yellow light in the windows” she sees as she “walk[s] the dog in pajamas”; it’s “the sponge and the sliver of soap” that keep things clean and tidy; it’s the “smoothies and hummus” and the “delicious bunch of lettuce” and the “hot cocoa on a faded couch.” These are the healing intimacies that connect us; they’re “our known environs” on an unknowable planet.

Our Known Environs: A Review of Julie Gard’s <I Think I Know You> was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.