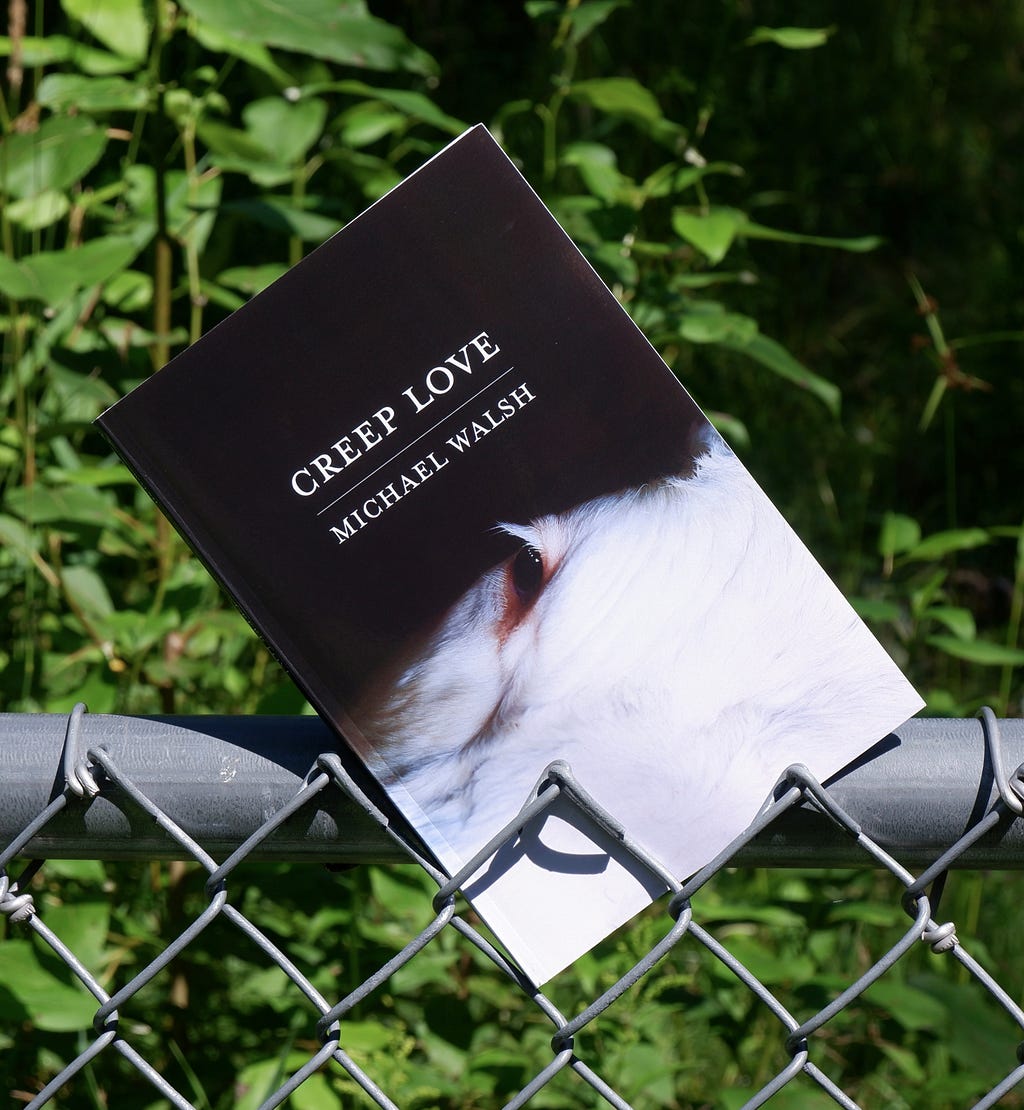

Imagine a midwestern farmstead. There’s a barn, a weathered farmhouse, the pasture that stretches between them … and the electrified fence that slices across the land like a softly humming threat. Within this tightly triangulated geography, Michael Walsh stages the domestic horrors at the center of his collection Creep Love (Autumn House Press, 2021). I use the word “stages” intentionally, because reading this collection often feels like watching a grippingly intimate chamber play. A small cast of characters populates most of these poems: the enabling mother, the absent biological father, the abusive stepfather, and the boy at the receiving end of the stepfather’s ceaseless beatings and limitless cruelties. As he comes of age, this beleaguered boy develops notions of love, family, and self that are inevitably warped by the violent environment in which he is trapped. What arises from these pages is a bracing, necessary chronicle of childhood trauma and a compelling account of its evolving aftereffects.

Walsh’s collection is built on a scaffold of recurring images and repeated events. The same key scenes of abuse are depicted over and over; the same key facts in the family’s history are rehearsed again and again; reiterated with slight differences each time. For as long as trauma has been a field of study, theorists have associated trauma with repetition. Trauma itself has been defined not as the original event — from which the psyche instantly dissociates, as a defense mechanism — but the act of remembering it. The individual thus “repeats” the original event by compulsively revisiting it in memory, attempting to achieve emotional catharsis through mastering it. In Walsh’s collection, these repeated rehearsals and reenactments accumulate, using poetic form to demonstrate trauma theory.

These poems also persistently reference another type of repetition that often haunts survivors: the anxiety that the abuser will replicate himself in the mind, body, or actions of the survivor; that the survivor is fated to repeat the violence and carry on the toxic legacy. Readers sense how Walsh’s speaker takes on this terrible burden even as a child, as when he likens his absent biological father to the serial killers in his mother’s pulpy true crime paperbacks, and wonders why “they never say what happens to the maniac’s son.” As he matures through adolescence and young adulthood, the speaker remains terrified that he has inherited the family’s monstrosity, either through nature (the biological father) or nurture (the stepfather). He polices his body and behaviors for any evidence of “this craze they released / inside my DNA,” worrying that other people can “really see / my father happening to my face / and brain.”

Alongside this poetics of recurrence, poems about altered states of consciousness and perception are woven throughout the collection, including imagery of dreams, nightmares, somnambulance, memory, and mind control. These altered states serve as parallels for the mental process of dissociation, another common trauma response. During his encounters with the stepfather, the speaker “evaporate[s] / somewhere deeper // than soul or brain,” relying on “the double who meditates / motionless inside” to operate his body for him.

As these incidents play out against the undulating pastures, dilapidated silos, and deserted backroads of farm country, the pastoral mode becomes skillfully corrupted. This is no romanticized canvas from the brush of Jean-François Millet; this is no bucolic montage of rural life. Rather, it is an act of witnessing. Although the child at the center of these poems must constantly flinch, wince, and recoil from his surroundings, the adult speaker submits his childhood memories to an absolutely unyielding gaze, often rendered in everyday naturalism or in the blunt language of reportage. Walsh’s traumatic realism thus produces a harrowing collection, in the word’s multiple senses: as farm implements, these poems distress the very soil they describe; as literary objects, they lacerate, wound, and vex the spirit. This book asks you to turn toward, not away. To accept the testimony of the wounded child. And to be honest about the complex selves we become and revise and discard as we stumble through the healing process.

The Maniac’s Son: Surviving Childhood Trauma in Michael Walsh’s <Creep Love> was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.