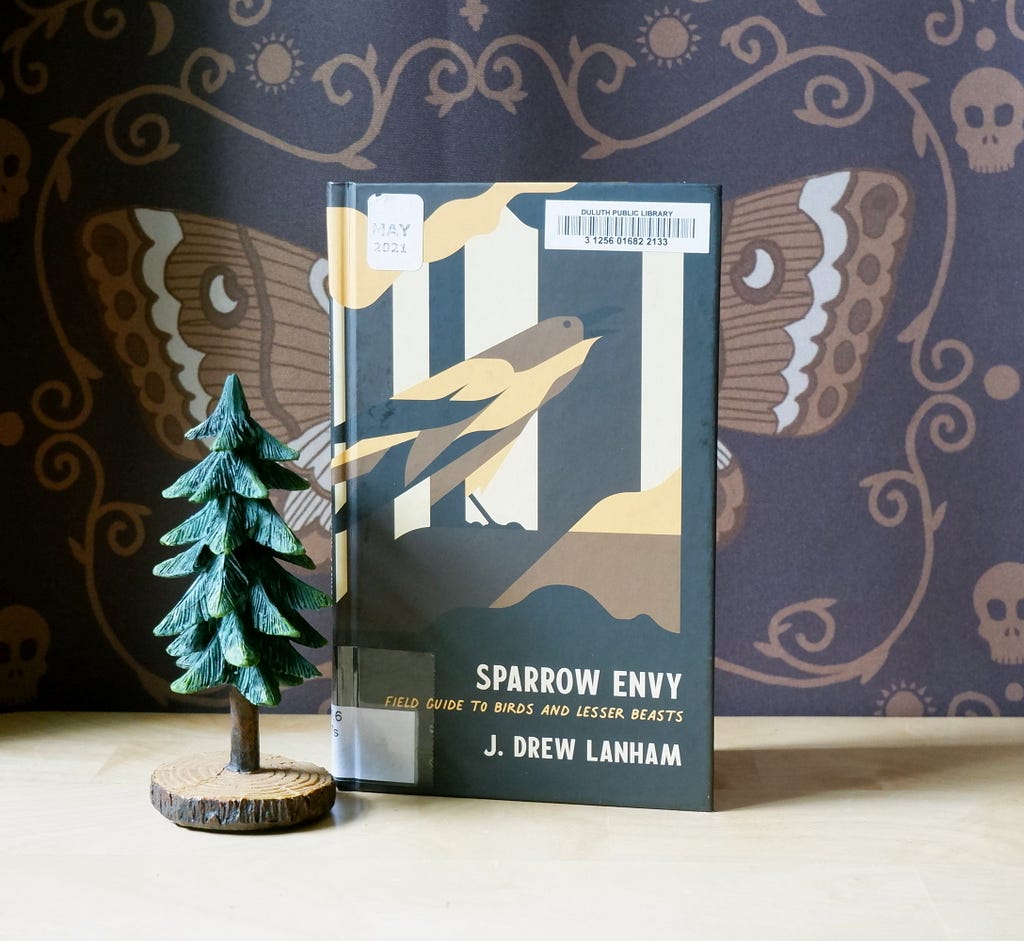

When it comes to my relationship with the natural world, I’m a late-blooming amateur. I’ve been obsessed with forests since early childhood, and I feel most at peace when I’m wandering through dense trees on a rustic trail, or standing on a rocky outcropping overlooking a body of water, the wind snarling my 4A curls. But even on my daily walks in the woodland that stretches behind my house, I encounter nature like a Romantic poet: I’m the unkempt hermit who’s enchanted by the dappled gloom, awed by the mosses, delighted by the rustling grasses and dancing wildflowers … but I could never actually identify a poisonous mushroom or distinguish a gopher from a chipmunk. I’m just the type of person who needs J. Drew Lanham’s collection Sparrow Envy: Field Guide to Birds and Lesser Beasts (Hub City Press, 2021), and maybe you are, too.

Despite the book’s subtitle, Sparrow Envy is no ordinary field guide. Yes, it features detailed descriptions of a wide array of (mostly avian) creatures in their natural environments, written by a professional wildlife biologist. But beyond that, this isn’t your grandma’s Audubon Society pocket reference manual. Readers venture into the overgrown foliage led by a poet-birder, the kind of person who knows and loves language as thoroughly and intimately as he knows and loves birds. As a result, these poems depict birds in a totally innovative way, wondering about their inner lives while also respecting their autonomy and implicitly acknowledging the gulf between human and avian experience. There’s such humbleness here — the speaker is content to observe and learn about birds without needing to capture them on his taxonomic pinboard or colonize them as an intellectual resource. He genuinely wishes them the best and wants them to be their gloriously simple selves. Put plainly, the speaker in these poems is friends with birds. In this way, the book gives us all a better set of images through which to frame our amazement for birds, and to genuinely befriend them.

The book offers very few concrete images, and those scattered throughout — “the rotting woodpile in the northeast corner / the honeysuckle tangle westward” — are sparse, simple, and ultimately fleeting, much like a bird’s wing flap. Thus, rather than offering up a painterly imagination, the book exudes a kind of sensory electricity: a murmuration of sounds, an assortment of pulsations, a burst of activity.

This is part of how the collection cultivates a pure exuberance that isn’t often on display in poetry, a giddy love of language unleashed in service of communicating enjoyment in everyday life. Yes, of course, Lanham takes his assigned duty seriously: the duty of faithfully witnessing the animal world and demonstrating how to responsibly participate in this ecosystem of which we’re all a part. But the speakers in his poems have so much fun in the execution of this duty. There are just a few moments — that much more surprising and effective for their rarity — when the speaker erupts into nanoseconds of exasperated despair about the world, snapping “how hard it is / to […] / even give a fuck what the name / of anything is” in this era of oppression, suffering, and planetary violence. But the majority of the book is lighthearted and zesty, opening its arms to welcome readers to a celebration of the planet’s avian inhabitants.

To be clear, that doesn’t mean the collection turns away from the sociopolitical dimension. Lanham is a Black birder, and so is the speaker of these poems, and the collection explicitly engages that theme because it’s an inevitable component of the experience. In “No Murder of Crows” the speaker acknowledges how the criminalization of blackness leaches beyond the social world and into the animal kingdom. He refuses to participate in the convention of calling a group of crows a “murder,” choosing to call them a “congregation” instead, because “profiling ain’t what I do.” In “Octoroon Warbler” the speaker forms a “taxonomic committee of one.” To “correct an oversight / of Manifest Destiny” he substitutes the names given to birds by history’s white European naturalists, renaming them “for what they are.” And in “Nine Rules for the Black Birder” the speaker advises, “Don’t bird in a hoodie. Ever.”

This last point is especially salient. The phenomenon of white people antagonizing Black people for simply existing in public is as old as our simultaneous presence on this land, much older than the nation itself. Black Americans have long carried a mental list of everyday activities for which white people target us with threats or outright attacks. The list’s typical entries — driving while Black, walking while Black, asking for directions while Black — have become increasingly bizarre and specific in recent years, as both state and vigilante violence against Black Americans has yet again become more visible to, and emboldened by, the mainstream. And in 2020, “birdwatching while Black” became the list’s next official entry, after an incident in Central Park went viral, in which a white woman menaced Black birdwatcher Christian Cooper. So when readers follow Lanham’s speaker “sneaking around in the nether regions of a suburban park — at dusk,” our hearts beat with anxiety for his safety as he “chases that once-in-a-lifetime rare owl” through the trees.

In spite of this constantly looming peril, the Black birder of these poems will not relinquish the joy of practicing mindful naturalism, nor will he dampen his reverence for birds. Readers cheer for this silent hero of the woods as he commits the “satisfying act of tearing apart a poacher’s stand,” and we understand that this act is both a literal and a metaphorical intervention into the brutal European history of the natural sciences.

A Congregation of Crows: A Review of J. Drew Lanham’s <Sparrow Envy> was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.