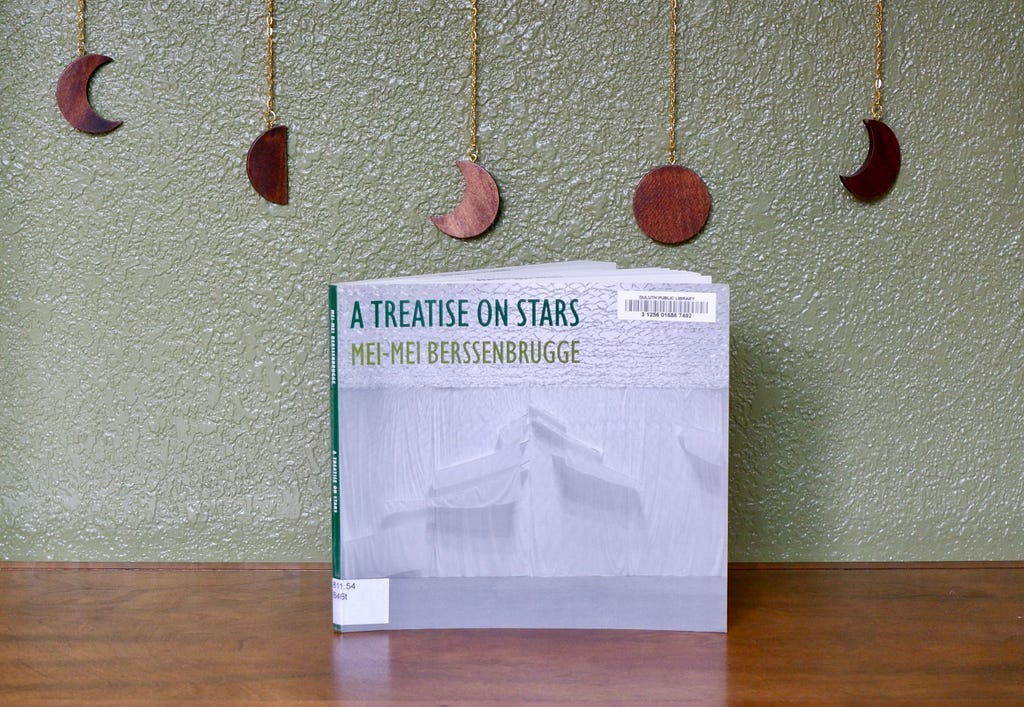

Particles, photons, meteorites, asteroids, constellations, morphogenesis. Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s poetry collection A Treatise on Stars (New Directions, 2020) reaches across the galaxies and collapses the space-time continuum, seeking “the unifying factor in all things” as a palliative for existential grief. The book asks “What is the structure of this connectedness?”, and looks for the answer in the interplay between atoms and energy, between human consciousness and the cosmos.

I envision the immortal speaker of these poems as a medieval poet who became a Renaissance astronomer and then wrote a Victorian physics textbook while on a Modernist spiritual retreat. Hailing from a tradition when science and philosophy were the same intertwined act of reverence, and often adopting genre conventions of old-world epistemology manuscripts, the speaker presents awestruck metaphysical ruminations on the universe’s fundamental nature, demonstrating through painstaking argumentation that “thought is a form of organized light.” In the universe described by this speaker, consciousness emits a substance and intentions generate energy, accrue particles, and become visible as matter.

Beneath the glinting precision of scientific language, a palpable ache lurks in the mist; a desire to be connected to — integrated with — subsumed in — everything else, on an atomic level. The speaker insists that “all is permeable, open to relation,” that “bodies and radiance are interwoven,” that “all life forms are in potential genetic exchange,” and that “a person, being of cosmic origin, can become one with a star.” The motive at the root of this insistence on radical interpenetration is the speaker’s attempt to assuage sadness or even bypass the painful process of mourning; to cling to the living beings who inevitably must die. Whether it’s a motherless fawn that starves on the roadside or a close friend who gradually passes away from illness, the bereft speaker implores to “be left with some essence of what has disappeared” or to “rise to a level of not knowing” that is “untouched by entropy” and “beyond decay.” The dead never truly die because all matter, energy, and light is perpetually interconnected.

I wouldn’t call this poetry “experimental” at all; the poems participate quite clearly in the lyric tradition. But the language is incredibly theoretical, so you’ll need a fairly high tolerance for abstraction. Tangible imagery is scant, and even the concrete nouns are sparse and undecorated by adjectives. Thus, despite the collection’s insistence on sight as the most important sense, these poems are implicitly asking readers to think and intuit rather than see.

As a result, the reading experience can be slow and ponderous … but I mean that as the highest compliment. Each line, and in some places each clause, is rich with wonder and discovery, yet hums just beyond the perimeter of comprehension. You’re forced to whisper the words to yourself, then look up from the page, stare out the window, and quite literally ponder. You can feel the concepts percolating, the sensations tingling into coherence. Reading this book is like working a spell on yourself: the poems ignite chemical changes in your body, producing a mysterious conversion of energy. By the end of this process, you too can “look inside when you are struggling” and see with absolute clarity that “every cell in your body emits light.”

Bodies and Radiance: A Review of Mei-mei Berssenbrugge’s <A Treatise on Stars> was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.