The number of American families experiencing homelessness increased by as much as 9% during the Great Recession. In the wake of that event, it took several years for many precarious communities to return to economic stability, and then, a pandemic descended upon us. Today, those of us who live in large cities have noticed the increased visibility of people forced to live on the streets as a direct result of the last decade and a half of economic tumult. Many of us find ourselves encountering unhoused individuals asking for help with food, money, shelter, or a job. Too often we brush them off, or hurry by them, clutching our bags and purses, forestalling any possibility of interaction.

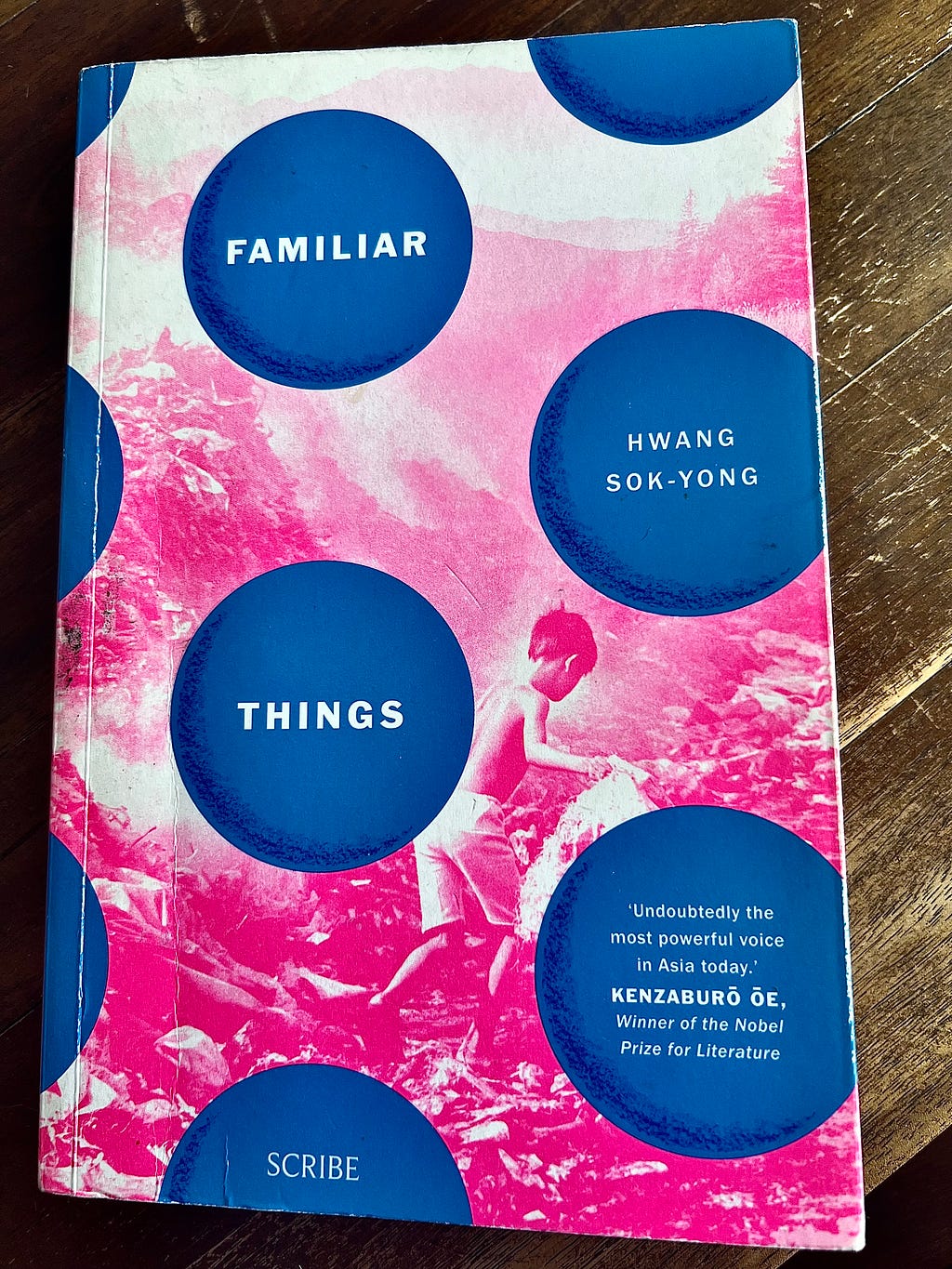

Originally published in Korean in 2011, during the world’s slow recovery from the global effects of the Great Recession, Hwang Sok-Yong’s novel, Familiar Things, about a thirteen-year-old boy forced to live in a garbage dump with his mother, captures the devastation wreaked as a result of unfettered capitalism. The timing of its English publication in 2017 perhaps did not lend itself to the same sense of urgency it might have in 2011. Today, however, as we grapple with the economic impacts of a global pandemic, Sok-Yong’s steady, unflinching gaze into the face of poverty seems, once again, very timely.

The protagonist of Familiar Things, thirteen-year-old Bugeye, lives with his mother in a dump on Flower Island, in a shack made of materials gleaned from heaps of garbage, and he helps her pick through trash for recyclables they sell, clothes they wear, furnishings for their homes, and even the food they eat. Unsurprisingly, Sok-Yong’s novel functions as a damning critique of conspicuous consumption, the devastation wrought by industry, and the waste generated under capitalism. And while we might want to look away from this, he simply does not allow us to.

In a Guardian review of Familiar Things, the writer suggested that Sok-Yong’s novel should be read for its content — not its beauty, arguing that, “Familiar Things is not particularly notable for vividly rendered detail, singular language or voice. But the measure of a novel is not only its artful telling, but also the power and value of the story being told.” While I agree that now, more than ever, the content of Familiar Things is deeply relevant, I disagree with the notion that Sok-Yong’s novel is not “notable for vividly rendered detail, singular language or voice.”

When Bugeye’s mother first moves to the garbage dump to become a trash picker with a man who is not her husband, Bugeye accepts his fate, thinking to himself, “There was no point in throwing a tantrum over his mother sleeping with another man, because the fact was that this land had no number and no address, and everyone and everything there was of no use to anyone” (45). Bugeye’s observations are devastating, and Sok-Yong maintains this kind of unrelenting clarity of vision consistently throughout the novel. In doing so, he creates a profound opportunity for empathetic understanding that might otherwise be unavailable to many readers.

Too often, novels that engage with overt social or political critique are dismissed as simply political tracts. Familiar Things isn’t simply a polemic. It is a painstakingly crafted narrative that takes risks in the service of emotional authenticity, thus preventing what could be an easy descent into cliché. Sok-Yong renders Bugeye’s experiences in spare, precise prose that avoids sentimentality despite the many losses, abandonments, and deaths he experiences. We understand this world through Bugeye’s reactions to his circumstances, not through his reflections upon his feelings. Survival, happiness, human fulfillment — none of these are possible if he doesn’t get up every day to help his mother pick through trash. Many of us who have experienced trauma, particularly trauma enforced through oppressive social structures and mores, know that the demands of survival rarely give us the opportunity to process our experiences and feelings. In this sense, Sok-Yong’s rendering of Bugeye is searingly true to life.

And yet, Bugeye and the other children of the dump do find ways to wrest moments of peace and reflection from the heaps of garbage that surround them. The children construct and enjoy a special hideout where, “they didn’t have to put up with the night-long din of grown-ups cackling and fighting and singing, which sounded less like music and more like pigs being slaughtered” (90). Sok-Young’s deft evasion of cliché is so clear here: he doesn’t tell us how lonely, abandoned and frightened the children must feel. He shows us that they’ve created a secret hang out to escape the sounds of their parents trying to cope with the misery of their existence. When the children compare the sounds of their parents’ desperate revelry to the dying cries of animals being led to their death, Sok-Yong reveals the children’s keen awareness of the brutish nature of their lives, dwelling and working as they do in filthy, inhumane conditions.

When dokkaebi, creatures from Korean myths, visit Bugeye and his friends, Sok-Young shows us both the history and possibility of Flower Island as a place of natural beauty that existed long before the dump. The dokkaebi are ghosts of villagers who once lived there, and as they wait for them, Bugeye notices that, “The moonlight was different from electric lights: it hid the ugly things, and turned the river and trees and grass and stones and everything else close and familiar,” (116). Again, we experience the subtlety of Sok-Yong’s artistry — the light of the moon not only hides the ugly detritus of modern-day industry, but it also reminds us that the river, trees, grass, and stones should be most familiar, because the relationship to the natural world should be innate to the sense of self. Despite the terrible events that later beset them in the garbage dumps of Flower Island, the dokkaebi remain touchstones of the natural world, perhaps the last refuge for Bugeye and his friends from the destructive impact of capitalism.

Hwang Sok-Yong’s Familiar Things is both lovely and necessary, a political indictment and a deeply affecting dive into a young boy’s fight to live through extreme loneliness and hardship. Familiar Things shows us that, even when trained upon the ugliest of subjects, the unrelenting gaze can be beautiful, instructive, and just.

Sok-Yong, Hwang. Familiar Things. Scribe Publications, 2017.

APIAnionated: Achingly Familiar: A Review of Hwang Sok-Yong’s Familiar Things was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.