raia reviews (your Black media hub):

“Like the sun and the moon”: A review of Davon Loeb’s The In-Betweens

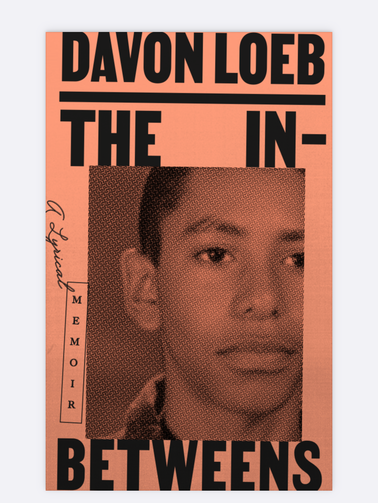

His mother’s troubled sister, Sammy. His half-brother, Alex, walled off from the world. The man he knew as Dad, though he wasn’t his biological father. His other half-brother, Troy, and the only other black teacher, Richard Downey, at the high school, though this later on. (The names matter.) Way back when, minoritized teenagers from out of town, not of the Pine Barrens, who arrive to play football, “star[ing] in disbelief, in fear, in anguish” at the Confederate flag “mounted on one super-duty diesel” in the parking lot pre-game. Davon Loeb’s “lyrical memoir,” The In-Betweens, out this year from West Virginia University Press, recounts and considers for meaning the memories of a life, his own. But the book’s dedication, heartrending like the memory of those startled kid-athletes before that starred-and-barred flag, is “to all the bodies that became [his] memoir and to [his] wife and children.” It is to the brave, searching treatment of others in this well-turned collection (for the memoir is fractured, broken into short, self-contained essays) that we, as grateful readers, might turn our attention — and not only to the narrating “I.”

Perhaps this is no surprise: memoir always reaches beyond the self. And Loeb writes in the tradition of racially mixed writers — specifically, writers (beating-heart bodies) set down between blackness and whiteness: Nella Larsen, Langston Hughes, Jean Toomer, Danzy Senna, Natasha Tretheway, the Kentucky poet and essayist Keith Harris. The mixed writer (mixed body) can’t help but look here, there, and everywhere, an attempt to piece things together. (Once, a friend told me that in the hallways of our high school, I was always looking, surveying, as if, I think now, a mapmaker.) I mean, life can flummox any of us, any time, but the race-skin equation gets all the more complex when, as Loeb writes, your white classmates think you’ll be a great dancer because you’re African American, and when your African American cousins, during summertime stays in Alabama, call you White Boy.

If Loeb writes to and for “all the bodies” in these lyrical rememberings — some, like “Quitting Meant Back to Babysitting,” measuredly essayistic, and others, like “In-Between Sirens,” partaking of the riff — then he does so with commendable empathy and care. He turns, in his acknowledgments, to his late grandmother, a woman (soul-body) most present in the book’s early, Alabama section, stating that “there is real danger when taking on someone else’s narrative, as if taking on their body, becoming them.” Then, Loeb writes, straight to her: “I hope that I told your story with love and conviction.”

I feel Loeb’s love for others when he remembers Alex, his father’s other son, gifting him a copy of his poetry collection in a New Jersey diner before retreating to the car, a young Loeb (Alex is older, in college when Loeb is still a kid) and their father still eating. I feel this love in “Bath Time,” a flash essay focusing on Loeb’s half-sister, much older than him — how she’d take care of him and Troy when the hot water went out, setting pots to boil on the stove. I feel this love when Loeb recollects Sammy teaching him to prepare a glass of Kool Aid: how to stir in the red powder for a sweet drink in submerging deep-southern summer, even as the memory reflects also her alcoholism; Loeb seems to say, more or less, Aunt Sammy taught me this. (I think of a tennis teammate, a man in his sixties, who recently taught me to more tightly and quickly regrip my racquet, to hold the grip in place and rotate racquet’s handle, to hold the tension from handle’s bottom to handle’s top. On occasion, of course, we’re taught small tricks, never forgetting.)

This is memoir, The In-Betweens, but what I love best here, yes, is Loeb’s attention to those shaping the self, even as his empathy gets turned back often on the self. In a difficult essay, “For My Brother,” Loeb meditates (via direct address) on Alex’s schizophrenia, recalling scattered interactions throughout their youths. (Loeb lived with his mother and would see his father’s family but rarely.) We look at Alex as his half-bro did when young: “I wanted,” Loeb writes, “to be just like you.” And we witness Alex lose himself in the whirlpool of an adult life tossed by severe mental illness. Near essay’s end, we come to understand that Loeb hasn’t seen Alex in a long, long time. He writes: “Maybe it’s safer because you’re sick, so I can keep my distance. Maybe if I pretend you aren’t here, you won’t be. Maybe you’ll forget about me, and maybe I’d prefer it. Maybe I’d feel safe, away from you.” (We know, of course, that his declarations don’t touch what the prose writer Calvin Baker calls the psychic core: blood never forgets blood, and blood-brothers don’t vanish just because we can’t well abide their presence.)

But then Loeb gets to that center, saying to Alex, who may or may never read this book: “And maybe I’m just afraid to become you.” The moment is poignant, hard, empathic in its honesty: it is loving.

Of course, not “all the bodies” in this book belong to folks with whom Loeb cannot entirely contend. In “Morning Noise,” a moving essay midway through The In-Betweens, Loeb thinks of his mother’s husband, a trucker who’d rise in the dark to drink his coffee, body toughened “like rebar.” On this morning (this night; it is 3 a.m.), Loeb’s a teenager, and he’s been out drinking. Comes home as his day-by-day father readies to leave: “When finally I opened the back door, the pale light from what was left of the moon split our faces in two.” (And the image of the moon “split[ting]” father and son’s faces says much, including of skin: Loeb is quite light, his day-to-day father brown, not so mixed, even as we’re most all mixed somewhat.) Loeb: “He stood and watched me stumble into the kitchen. He said nothing, and our bodies, like the sun and the moon, moved past each other.” Because Loeb, in an earlier flash essay, “To Be a Man,” has cast his day-to-day father as archetypally good (steady, tough, loving even to children not his own, for he’s not Troy’s biological father, either, or Loeb’s half-sister’s father; the families in this book are mazy, love and loss intermixed), we know that here, he has not lived up to Dad’s image. (Of course, he is young, not yet a man anyway.)

The call-and-response action between “To Be a Man” and “Morning Noise” is among the most effective structural moves here, comprised as Loeb’s memoir is of intermixed parts: a life-in-mosaic (or the portion of a life during which one matures: a bildungsroman-bricolage). Sometimes this suspension (as in music, when a chord’s quality is neither major nor minor but in between, and the ear waits for resolution) happens fast: in “Something about Love,” Loeb’s mother says that his biological father “never learned to love,” or didn’t learn right; next, in “Visitations with My Father,” we see Loeb’s father take him to get a tattoo; Loeb writes, “I think that maybe my father was just showing me that he loved me.” (Maybe this isn’t quite suspension but a change in tonality, a recasting of what we’ve read earlier, a complication, lovely — the addition of color tones: he loved and didn’t love; he was a whole person; he sometimes fell short but did try.) In another instance of such essay-to-essay intermixture, Loeb gives us “Gym Rat,” about his body-building obsession; he’s long wanted to put on muscle despite his lean body type. The essay is entertaining and vulnerable but becomes stronger, to my mind, through later pieces, “In-Between Sirens” and “A Small Lesson on Loitering,” about violences against black and brown beating-heart bodies. I began to question if being muscled was also about dealing with the precarity of skin, at least internally: I’m strong enough.

In its treatment of faith, Loeb’s memoir departs from, for instance, Larsen’s Passing: while his mother is African American, his father is Jewish, and his paternal grandmother lives on Long Island. Loeb writes, in “The Black Jew,” about coming from “two of the most historically discriminated against people in the world.” This fact bothers him as a teenager, and so, too, does the fact of blood-distance: when his paternal grandmother dies, Alex calls. He’s trying to reach their father, to tell him the news; Loeb answers. Alex says, “Tell Harry my grandmother died.” (Not, Loeb writes, our grandmother.) Loeb gets his artistic side from his father’s family: in the apartment where his father lives before moving to the mountains of Pennsylvania, there’s a small, wooden sculpture of a woman; when Loeb asks about it, his father says, “I made that”; Alex writes and paints. But at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, Loeb looks up his last name and sees a long list of Jewish people in a database of survivors and victims. He calls his grandmother then; he wants to ask her about their family history, which to him remains a black box. She doesn’t recognize his voice. (This, too, is passing.)

The In-Betweens, then, deals in gaps and in dichotomies, sometimes bridgeable, others not. Masculinities: Loeb plays tons of basketball as a teen but also makes art and is chastised by an uncle, when younger, for play-acting with dolls. Geographies: northern Jersey, the southern Pine Barrens once written of by John McPhee; Alabama, Long Island. “My father,” “Dad”; Blackness, Jewishness; others, the self. And I’ve been thinking for a while that every essay worth anything is a love letter. Well, Loeb’s casting that letter in lots of directions, to lots of bodies. It’s a missive, with a sender and many recipients, even folks he doesn’t speak to anymore.

raia reviews: was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.