I’m a vulnerable narrative. Who am I and what have I done? Breath catches. Somatic wisdom: the body remembers. — Stephanie Heit

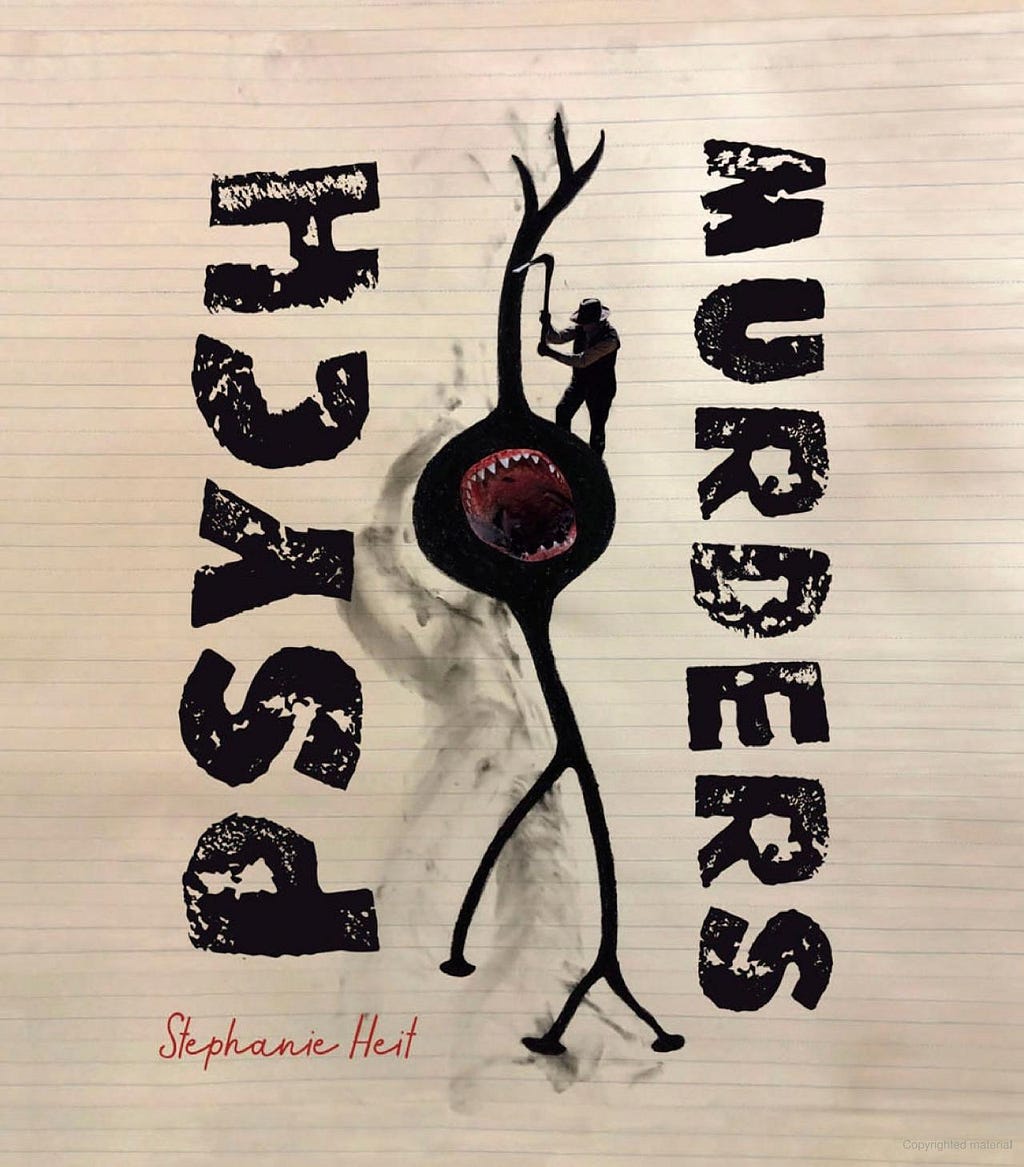

At the start of the poetry-memoir hybrid Psych Murders (2022), author Stephanie Heit addresses the reader, gently letting them know on the very first page of the story, “Please take whatever time you need to be with these words.” This care and thoughtfulness are threaded throughout the narrative as she pulls back the curtain on her experiences with mental illness, suicidal ideation, and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Heit’s involvement with mad activism makes her the perfect person to write this book. Mad activists are working to ensure that those with mental health challenges are empowered to use the language they feel is most fitting to describe themselves and relate to the world. In an interview with Brilliant Books’ Dunes Review, she describes one of her achievements as an activist: “I had a person tell me she was going to ask a loved one more about her mental health experiences after hearing a certain piece. This is my mad activism, to openly share my experiences with mental health difference, to raise awareness and open spaces for dialogue.” This work continues in Psych Murders.

Readers follow the speaker, who we assume is multiple versions of Heit — who is queer, disabled, and bipolar — through the high and low cycles of mania and depression. Her precise use of language describing her mental state — she compares mania to a hyena, and depression to a turtle, for example — combined with her detailed somatic experiences carry readers deeply into the narrative. She guides readers through her journey, and she doesn’t exclude anything about the ECT process and its terrifying, painful side effects. After reading about the extreme mental and physical discomfort that accompanied each session, it’s impossible not to feel the dread she describes as her ECT sessions approach.

Heit turns her suicidal ideation into a character all its own: The Murderer. Her dark humor shines through here, including a section titled “The Murderer: 401K,” in which The Murderer celebrates their career: “People ask how I keep up my impeccable record. I’d like to say persistence, dedication, passion, those trademark American work ethic values.” As her mental state fluctuates, so too does The Murderer’s confidence. The Murderer is peppy when the speaker is at her lowest; when she experiences healing, he becomes insecure and resentful.

The Murderer is always there, whether in the background or foreground of the speaker’s mind, such as when she quips, “The big claim of support groups is the YOU ARE NOT ALONE diatribe. I know I’m not alone. I have Murderer stalking my every move.” Heit’s dark humor reminds readers that books focusing on mental illness and suicide can also contain moments of levity, even humor. Even when she is recovering from ECT, she still makes wry observations: “Bed side rails up to keep gravity at bay. This month the psych unit won the demerit for most falls.”

Heit eventually includes observations of ECT sessions that took place at the hospital where she had her own treatments. The speaker is overcome with emotion, and her mind returns to her own experiences: “I want to know what happened to my body while I was away. Who touched me. What pressure. Where. During the seizure what did my face do.” She is aware that she does not have complete autonomy over her body during her time in the psych ward, especially during ECT — she’s given up control in order to get help. Here again, her wording prompts readers to ask themselves similar questions, especially if they’ve had experiences in the mental health system. What happened when they were asleep? What happened when they were given sedatives in the hospitals to quiet their emotions?

In Heit’s Artist Statement on her website, she states: “My inquiries delve into somatic experiences and how the body inhabits the page, words inhabit the body, and how the environment we place our bodyminds in can stimulate new awareness.” In addition to being a writer, teacher and activist, Heit is also a dancer. Her background in dance and her focus on somatics allow her to place the mind-body connection — her mind-body connection — at the center of the narrative.

Even when her body is overcome with the electricity from ECT, the speaker notices that her right foot is the only part of her body that moves. Heit returns to this idea throughout the memoir, with this small movement providing a connector between her ECT sessions. After she’s finished her series of treatments, she reveals, “I develop pain in my right big toe joint… It was awake for every session.” The idea that her toe held that pain along with her mind brings the reader back to her early observation: “the body remembers.”

Heit also notes in her Artist Statement, “Water flows through my work as vehicle, home, vibration. Movement creates new choreographies on the page.” Water appears again and again in Psych Murders as her mental health ebbs and flows. When the speaker is hooked up to saline in the hospital, she dreamily writes, “My body fills with the sea.” As she observes other people receiving ECT, she notes, “Like tides, patients roll in and out.” And most heartbreakingly, when she struggles to regain mental clarity after a treatment, she shares with the reader, “I swam. Too deep to return to the name on my wristband.” She’s out past the area where most people swim, and she’s not sure if she’ll return as the same person with the same memories.

By writing Psych Murders as a poetry-memoir hybrid, Heit helps build up this newer and lesser known genre. Shorter prose sections are mixed in with poems, keeping the reader engaged as she moves effortlessly from form to form. Ideally, this book will not only destigmatize mental illness and make it easier for people to speak about it (after all, she stated in her Brilliant Books’ Dunes Review interview that she wants “to raise awareness and open spaces for dialogue”), but it will also bring more attention to new ways in which artists can convey their experiences.

In Psych Murders, Heit invites the reader into her innermost world. No matter the readers’ experience with mental health (and the mental health system in the U.S.), they’ll be able to learn and better understand the challenges that bipolar people and those who experience suicidal ideation face. Although the speaker tells The Murderer, “You crowd out beauty,” the beauty of Heit’s words, observations and rhythms make this poetry-memoir hybrid an important and revelatory book.

The Body, the Mind and the Mad Activism of Stephanie Heit’s “Psych Murders” was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.