An Interview with Diane Seuss

On Monday, May 19th, 2022 I had spent the day in the hospital. I was the first scheduled procedure of the morning. They were cutting into my neck, specifically my carotid artery, to install a port for my initial infusion of chemotherapy. The nurse put her hand on my shoulder and asked me if I had any children. A niece, I said. My brother and his wife had given birth shortly before my diagnosis two months ago. I told the nurse I hadn’t held the baby yet. She didn’t move her hand from my shoulder until the procedure was over.

The next nurse said my dressing was wrong and that it would hurt too much to change it. She put on a special outfit to deliver the chemicals, festooned in biohazard bags, to my body. I thought I would spark. I thought I would glow. I kept waiting for something to happen as the machine whirred and clicked.

I tried to think of a league of microscopic Avengers leaping into my body to eradicate my cancer, led by the Incredible Hulk. The nurse unhooked me from one machine and gave me another tiny one to take home — a slow drip for 46 hours. I named her Captain Marvel.

Once home, my father-in-law, a cancer survivor, said he wished he could hug me. There was no part of my body that didn’t hurt. I had tape all over my neck and chest and an orange residue that would remain for two days until I could return, get the pump removed, and shower.

I was tired and opened Twitter for no reason at all except to think about something other than my body. The first tweet I read was Diane Seuss had won the Pulitzer Prize for her collection frank: sonnets. It was the first time I smiled all day.

I was lucky enough to have been one of Di’s students at the University of Michigan in 2019. Then, I was thirty-nine and easily the oldest person in the MFA program. I felt ancient and out of place. No one made me feel that way, I just did. I still carried some of the trauma from my other master’s degree with me. Twenty years ago, I dropped out of an MFA program and moved to New York to finish a degree I didn’t even want. I hated the city. Once, in my Magical Realism class our professor asked us what kind of animal we imagined ourselves as. We went around the room and everyone picked something fierce like an eagle or a great white shark and because I missed home, specifically my mother, I said I was a Northern Cardinal. The birds reminded me of her because when I was a child, I was mesmerized at how she could whistle at them and get them to whistle back. I thought she was magical. With this answer, I was immediately asked where I was from. When I said Michigan, laughter ensued. I didn’t get it. Cardinals are everywhere and pretty fucking cool looking with their crests and eyeliner. They are one of the very few female species of Northern songbirds who sing.

To say I love eyeliner is an understatement. I adore it! My mother used to heat her pencil on a bare lightbulb to warm the black she smeared on her eyelid, and then out into a wing. So, from the second I picked up four-legged girl and saw those dark cat eyes gazing back at me I was hooked on Diane Seuss and her hip Liz Taylor vibe. I couldn’t believe that due to a last minute change in professors during my second semester of grad school, I was going to get the chance to work with her. I didn’t know what to expect.

On the first day, she had us write American Sentences (a single sentence containing seventeen syllables). She wrote with us and she shared her poems too, but she was also listening — honest to god listening to what we said and how we said it. Not that the other professors didn’t do this exactly, but they always seemed put out and Di seemed genuinely interested in understanding what we were trying to do.

She wrote half a page long (at minimum) commentary on our poems. Typed, single spaced. Up to that point in my MFA, I had only received circles or lines through my improper use of grammar and question marks where I was evasive.

But Di told me to take up space.

Perhaps it sounds silly to say, but Di gave me permission to be myself, and to write what I wanted to write. She said to us, my goal is to give less fucks and I already don’t give a fuck.

*

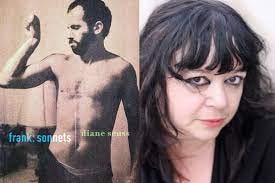

Di is the author of five fabulous poetry collections that are from the perspective of a working class rural Michiganian and are one hundred percent unapologetically herself. She is a recent recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and the John Updike Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Her latest book frank: sonnets, won the 2022 PEN/Voelcker Award for Poetry, the 2021 National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize in Poetry, and the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

I revisited frank: sonnets while receiving three chemotherapy infusions, followed by two trips to the emergency room, and one hospitalization. Di’s book came with me while I faced profound uncertainty. And during those moments, when I needed most to hang on to something, I kept hearing her line, I hope when it happens I have time to say oh this is how it is happening. It frightened me, yet I agreed with it. There is no reflection, only a brief acceptance — a reckoning, perhaps. So, it was with great veneration for Di and her work that I began this interview over email during what few moments of coherence I felt I had, and I was grateful to reconnect with my absolute favorite poetry professor and poet of all time.

MONICA RICO (MR): What drew you to reinvent the sonnet and how does it feel to know that when folks talk about this form, they will be mentioning you, Shakespeare, and Hopkins in the same sentence? Is it strange to think about thousands of undergrads and MFAs laboring over creating an imitation of a Seussian sonnet for their workshop?

DIANE SEUSS (DS): HAaa, oh my GOD, Monica. To be perfectly real with you, I still feel somewhat invisible and marginal, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. bell hooks describes the margin as “a space of radical openness.” Toni Morrison writes, “I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central. I claimed it as central, and let the rest of the world move over to where I was.” I’m not sure I feel much confidence about the world moving to where I am, nor even that where I am is a place the world would want to move, but I do inhabit a margin that feels, for me, to be a space of radical openness. Certainly, as a teacher, I plopped down on the margin and hoped the students would sit there with me, and encounter their own marginal spaces, and discover a degree of radical openness in their own work.

Maybe part of my difficulty with absorbing all of this goodwill toward frank: sonnets is that it has happened during the pandemic, and so in a sense it all feels virtual, or conceptual. My life is pretty much the same as before, though all this love and connection has come my way via messages, emails, and beautiful flowers. I’m trying to receive — which has never been easy for me. It’s so meaningful to me to hear from people who say they feel included in frank’s honors. That’s exactly how I would want it to be. I did drive to the old village cemetery where my dad and grandparents are buried. I told them all about the awards, and thanked them for working so hard on my behalf. That felt real.

It would be cool to be in the company of William and Gerard Manley, to be in that conversation, along with Keats, who I swoon for, and talk with Gwendolyn Brooks about her sonnets, and her fabulous “sonnet ballad,” to Wanda Coleman about her jazz sonnets. I love Joan Larkin’s “Blackout Sonnets,” Bruce Lack’s heroic crown, “Our War,” in his book Service, and Gerald Stern’s book American Sonnets, and Terrance Hayes’ Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, and a thousand other etceteras. And of course, I’m excited by the younger writers bringing all kind of fresh energy to the form, like Trevor Ketner, with their forthcoming book The Wild Hunt Divinations: A Grimoire, that Ketner describes in a tweet as “154 sonnets that are kinky, queer, and full of pre-Roman British folk belief, ritual, and practice,” and are also composed via a process of the rearrangement of the words in Shakespeare’s sonnets. I mean, in this company, I can’t claim any kind of exceptional relationship to the form. Only my own relationship, which seems to have found its space.

MR: I admire how the sonnet form doesn’t own you and you are in charge of it. When I arrived at the middle section of your book and unfolded the double wide pages of the collaborative poems between you and your son, I felt something change in me. I felt my brain unravel like how pollen jettisons from the pine and clings to every available surface. What was it like to work with your son? This isn’t the first time you’ve done so — he made the photo for your book Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, right?

DS: I love your pollination image, Monica. It’s an apt description of what can happen when a reader takes the leap of making a connection with a poem, or even having a relationship with it over time.

I’m not sure that when writing frank I was in charge of the sonnet. I have a pretty respectful relationship with it, as I might with a tiger. I did, however, feel permitted to experiment, as I always have in my poems. I don’t see experimentation as being in charge so much as paying attention. The worst thing we can do to forms, poets, poems of the past — to me — is to not pay attention to them, even if we struggle to understand, or have trouble suspending judgment. I really wanted to test the limits of the form, to stretch it, as you mention, into the double-wide poems on the centerfold, to punctuate or not, to be music-forward, story-forward, rhetorical, personal, less personal. How could the poem remain true to at least vestiges of the tradition — using a kind of volta, for instance, or something like a couplet, rhyme, even if internal, meter, if only in certain lines, as a kind of reminder of what I’m working with, without simply clicking into the template.

I’m glad you asked about the poems that were collaborations with my son. (And yes, he did make the photograph that is the cover of Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open. It is a calotype of the actual Wolf Lake made with a camera he built.) I didn’t really decide there would be a sequence composed of dialogues with him — not so much about him as biproducts of our conversations — but I started saving transcripts of those conversations because they were so interesting to me, and charming. I then had the thought that I could frame and arrange parts of those conversations into sonnets. I hope this sequence forefronts Dyl’s voice and the give-and-take of our interactions, which reveals something of the nature of our relationship now, which has struggled through so much shit. I do have some poems in the book that include Dyl as a subject, a part of my story, but I wanted to offset that more conventional approach by giving him the mic. The poem on the flipside of the centerfold is his. It felt important, especially given the nature of my own long poem on the other side, to let him tell another dimension of his story without my intervention. Of course, I showed him everything, and got his permission to include it all in the book. This is the most collaborative aspect of frank, but the book is composed of many contributions to the project, sort of like stone soup — from the photograph of my friend Mikel on the cover, taken by his lover and friend Alan Martinez, to lines from Alan’s own poems, to sonnets built on some of my mom’s adages, like “wish in one hand, shit in another,” to conversations about music with my friend, composer Kurt Rohde, to snippets of text from writers like Joyce and Chekhov, to landscapes in Washington and New Mexico and Colorado, to the sonnet itself, my ultimate collaborator. This gives the book, for me, its breadth.

MR: I connect with how you are talking about being on the margins. Do you feel this is something inherent to you or perhaps even writers from the Midwest? Even Jim Harrison titled his memoir Off to the Side, describing in earnest what he thought his position was in society, but he too eventually left Michigan, although he never stopped writing about it. So, there is something deliciously delightful about you being the first Michigan poet to win the Pulitzer Prize while actually still living here. I was talking to the poet Keith Taylor and he reminded me that both Roethke and Levine had long left the state by the time they received theirs.

DS: It’s certainly not inherent only to me. I think many of us in the Midwest, in the flyover states, as they’re called, yes, are marginalized in very real ways. And of course, there are massive numbers of people who have been systematically marginalized. That goes without saying, but must be said. Basically, anyone who is not white, economically privileged, conventionally beautiful and abled, cis, het…as Elvis would say, plus tax. One can make the argument that most writers and other artists are, by nature, marginalized, at least at this point in American history. I inserted “American” because it’s the only place I’ve observed enough, close-up, to speak about in grand generalizations. Some, of course, are more marginalized than others. And those who are marginalized and thereby claim the margin as a location of power are many.

You know, I didn’t realize it, but you’re probably right. I may be the first Michigan poet to receive the Pulitzer without having first left the state for one of the coasts. I take a little pride in that. I’m thinking of Terry Tempest Williams’ words, “Perhaps the most radical act we can commit is to stay home.” I have lived in many other places, but I always circled back. All places are places, you know?

MR: In frank: sonnets there are a good number of poems that deal with your time outside of Michigan. I, too, moved to New York when I was younger, and I never felt more like a rube in my life. I noticed right away that I walked too slow, I hated not having a car, and I said pop instead of soda. I was there for about two years with my husband and once, when we found a cab driver that would take us from Manhattan to our crummy neighborhood in Brooklyn, he told us that the only ride he had given to this part of the borough was a hooker.

DS: HAaaa! “Rube” is the perfect word. My friends would say, “Quit looking at people when you’re walking down the sidewalk! Just walk! WALK!” I often felt trapped — that island fever thing. I felt it when I lived on Mackinac Island and I felt it in Manhattan. There were things about NYC I loved. Let’s see…what did I love…? I loved that I could wander around on my lunch hour and walk into a Soho gallery and bump into Andy Warhol and his new paintings, that I really thought were wonderful and uncharacteristic, or a gallery show of Frida Kahlo’s work before she was on calendars, socks, and fake fingernails. I loved the food, the neighborhoods, the grime, the lack of pretense that there was any such thing as purity. That Brooklyn hooker was probably me! I left because my life was in danger, but also, I always felt tilted there, like I just wasn’t where I belonged, you know? It probably would be easier now because I feel less connected generally to exterior reality.

MR: How long were you in New York? And how long did it take you to make yourself appalling “like drag queens and anorexics, I did / not want to be acceptable, I wanted to be alarming, hulk, colossus, / freak, maybe not a great life plan but a step in the right direction.” Or shall I say how long did it take you to reject the literary culture you were ensconced in — especially with the degrading treatment of the who’s who of the literati towards women? I was specifically horrified when I read, “The famous poets came for us they came on us or some of us / at least on some of us they did not come their poems were beautiful / or not but either way we learned to call them beautiful they came / like honey bees to hyacinths to some of us they came in some of us / the ones they called unreadable but fuckable or readable and fuckable / others were unfuckable” because of the predatory nature of this parasitic relationship. It reminded me a little of the scene of when Diane Di Prima meets Jack Kerouac in Memoirs of a Beatnik. Although Jack wants to prove that he is cool with his idea of womanhood by offering to go down on Diane while she is on her period, if I am remembering the book correctly.

DS: I was in NYC around three and a half years. I think I actually embraced “alarming” early, in my teenage years, but an alarming that remained seductive. The hulk and colossus probably grew in me after I left New York, and into and especially after my ill-begotten marriage. Divorce turns many women into freaks. By its very nature, it freaks you. Then, if you’re lucky, it frees you. Regarding the literary culture I describe in “The famous poets came for us,” I learned while an undergrad that the predation was part and parcel of literary culture. At the time, with no voices to tell me it didn’t have to be that way, I knew it felt violative but also it seemed like the only game in town. Being from a small, rural place, I knew nothing of the literary world. I probably didn’t even know the word “literary.” The closest young women could come to literary power was to fuck it. Isn’t that a horrific statement? It was really a kind of suicide for many of us — of our burgeoning hopes to be writers ourselves, to our selfhoods, our Selves. Regarding Kerouac and Di Prima — that scene sounded wild and I’m glad I wasn’t there.

MR: I was wondering if you could speak a little about how you formed this poem and the many others in frank: sonnets that are essentially one long sentence with little to no punctuation. I am so impressed by how you manipulate grammar in this book, especially these long flowing non-punctuated sentences because I never caught myself getting lost or hiccupped. I just dutifully followed your instructions and moved through the poem with ease, then shouted holy shit, how did she do that? And then of course, I read the poem again, and shouted yes! at your genius.

DS: Ah, that’s good to hear, Monica, because I never know if the way the poem lands on the page will sound the way I hear it in my head, and that’s how I compose, by ear. The sonnet form, even though I didn’t obey the traditional form’s full array of stipulations, helped me with holding these breathless, one sentence poems together, keeping their guts from falling out onto the payment, so to speak. Which poems required traditional punctuation and which absolutely needed to throw it off seemed very clear to me from the beginning. It’s all about the ear, sistah!! And I wonder if readers are willing to follow the poem’s instructions because they’ve built, with the writer, a relationship of trust. I hope that’s true.

MR: What I admire most about the poems in frank: sonnets are their memoiresque ordering. I feel as if I am allowed to look at one of your photo albums, but with all the photos captioned. I find myself heavily engaged with how the poems do not shy away from the unpleasant. To be honest, I feel that they reside there. Not in a negative way, but in a way that has no artifice, and is instead a strength. When you started frank, was this an intention?

DS: Your question gets at the value of the sonnet, the consistency of the form itself, to this collection. I experimented a lot with order, but I finally made the decision to arrange the poems in the chronology of their making. They are not arranged exactly with linearity, in terms of the sequencing of my life, but move forward with the movement of my thinking and imagination. The order, I’d say, is improvisational. The fourteen-line form provides a uniformity no matter the size of the subject, which I love. An amoeba and an elephant take up the same amount of space in a sonnet. Fourteen lines. I think your mention of the unpleasant is linked to the potency of the sonnet as well. The unpleasant, the pleasant, the angry, the tender, all live within the form. Having lived, fully lived, there’s no way to avoid the unpleasant, which is often simply the real. I think I wrote in a very early poem, which has since disappeared: “Scars are erogenous zones.”

MR: There is a sense of duality in these poems that is remarkably lucid — where the past self interacts with the current self. This hybrid narrator is perfectly balanced in “His body was barely cold” where I see both the perspective of an adult and child and their reflection on motherhood: “and how did she fend them off, the suitors, and go to college, / and read Ulysses, and write papers on that manual typewriter, and feed us, my sister and me?” This vision of the mother as protector returns to many of the poems where we are saved by her and not the father, which goes against what those of us who grew up around Christian doctrine were taught. As you can imagine, I am very into this flip flop, particularly when it digs its claws into more uncomfortable terrain, when the mother whose aborted children “scrape themselves free” becomes the mother who hoists drug addicts from her son’s basement apartment. Could you talk a bit about what it was like creating this hybrid narrator, where all the past selves are allowed to speak?

DS: This is (of course) a brilliant analysis, and for me, very true. It may be linked to what you write above about the unpleasant. All selves exist on a single plane. I compare it, in frank, to a strip of film, in which all cells are equal in size. The child’s eye view exists in the same fourteen lines as the adult’s, looking back, after a long-lived life. That is how the mind operates, I think. So many selves flow through a single instant. Little girl me remains within her present tense, with access to the wonder and the fear. Adolescent me pushes off from the known, the solid. Young adult me tries to get it right. Me the mother fucks up, corrects course, or tries to. Present tense me remembers, integrates the past with what she’s become. It all happens concurrently. In frank, I was interested not only in what I remember, but how memory functions; how it behaves. Yes, the mother, like memory, like pleasant and unpleasant, is a many-headed creature. My mother certainly was and is, and so am I, as a person, as a mother. My mother protected us in ways. At other times, she pushed us out of the nest. She didn’t live for us. For instance, after my dad died, she immediately went to college, which she’d not been allowed to do right out of high school. It was a pathway, an identity, a survival mechanism for herself, and thereby, us. I don’t think she got educated for us, however. I think she was, herself, surviving. My mother and I both found ways, sometimes subterranean, to remain ourselves. To remain free — at least a kind of free. That freedom is crucial to the ferocity it takes to hoist addicts and write poems. I do not idealize mothers. Idealizing them might make them pleasant. One can’t mother and be convivial. At least not in my family. I don’t know how to define love anymore. It actually feels a little cardboardy. I will say what it sounds like, to me, is the pounded keys of a manual typewriter at 3 a.m. writing a paper on Finnegan’s Wake.

MR: A theme from frank I keep returning to is the discussion of religion and mortality. There is a type of innocence in the beginning poems, from the perspective of the young girl who has just lost her father. It reminded me a little of the story of Adam and Eve, and how they didn’t know they were naked or should feel shame about it until they were kicked out of Eden and made temporal, so to speak. Childhood could be seen as a kind of Eden or as a momentary holding pattern, where we float above understanding what death means. How did your idea of mortality change while writing this book? I am thinking specifically of the transformation that you lovingly chain together in the final sonnet with the tracing of kisses.

DS: I am really interested in our definitions and experience of innocence. In fact, that’s something I contemplate more overtly in my next book. In frank, I’d say innocence is the child’s capacity to experience the world directly, without pre-ordained labels or explanations, without subterfuge. I don’t think of innocence as goodness, nor is it a state we can maintain. When my son was very young, I didn’t want him to ever have to lose his innocence. Little did I know. That is a cruel wish for any human being. The fact that we have such a deep relationship now is a direct result of our mutual lack of innocence. Our continuous loss of innocence. I can’t write poems from a state of innocence. I can remember my direct experience of the world in childhood, but even that memory is skewed by what was to come. To leave the Garden — well, even writing that phrase hurts. Yes, as you say, Eden, “where we float above understanding what death means,” must be abandoned. Life happens beyond the gates. Death too, obviously. I realized when writing frank that I couldn’t write about my life without writing about death, and toward my own death. The final poem, as you say, lays out that chain of kisses. To be remembered through a kiss, and hopefully a poem. The best eternity I can come up with.

MR: When we turned in our final project for your poetry workshop at the U of M you told us what kind of donut we were. You said I was a “Voodoo Donut’s Viscous Hibiscus — yeast donut dipped in hibiscus frosting with BLACK SPRINKLES.” So, I am wondering what kind of donut are you?

DS: Turnabout is fair play. (Can’t believe you remembered, but I’m glad you did because yours is truer now than it was before!) I’d be my great-grandma’s donuts made from leftover mashed potatoes, flour, buttermilk, nutmeg, eggs, baking powder, and sugar. After she fried them in hot oil and they ascended to the top of the pan, she’d remove them to a paper bag with sugar in it, shake it around, and put the sugar-coated babies on a plate to cool enough to eat. That’s me. The donut version.

Michigan’s Original Chingona: was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.