Murky borderlands, oscillations, and reversals abound in Carrie Hunter’s VIBRATORY MILIEU.

I don’t know about you, but my writing has been shaken by quarantine. This has looked like ignoring a lot of deadlines, but also shifting the bounds of what I’ll consider part of my “writing practice.” Yanyi’s The Year of Blue Water gave me a sense of permission to think of texting friends as a poetic practice. Eve Sedgwick’s A Dialogue on Love goaded me to crib academic reading notes and therapy notes alike. Carrie Hunter’s Vibratory Milieu inspires me to dive into my dream journal and film captions for material.

The effect of my jumbled quarantine practices may be slow to manifest in my own writing. But I can only hope that these efforts may one day coalesce with anywhere near the grace of Carrie Hunter’s polyphonic drifting notebook. Composed over a period of eight years, Vibratory Milieu collages dream images, aphorisms, movie lines, lines from journal entries, citations of feminist theory, conversations with friends, ripped headlines, and more, abstracted and laid side by side in a revery-like field of charged poetry-prose. Murky borderlands, oscillations, and reversals abound.

Vibratory Milieu presents a polyphonic portrait of the self composed from environs and its flux, a book composed in conversation. It comes in five sections:

I. Lusimeles (“limb-loosener” — Sappho’s epithet for Eros)

II. Carrie (with an intentional blur between the author’s name and Stephen King’s “creepy carrie creepy carrie”)

III. Per Una Selva Oscura (the shadowy forest at the outset of Dante’s Inferno)

IV. Oppositions Are Accomplices

V. Vibratory Milieu

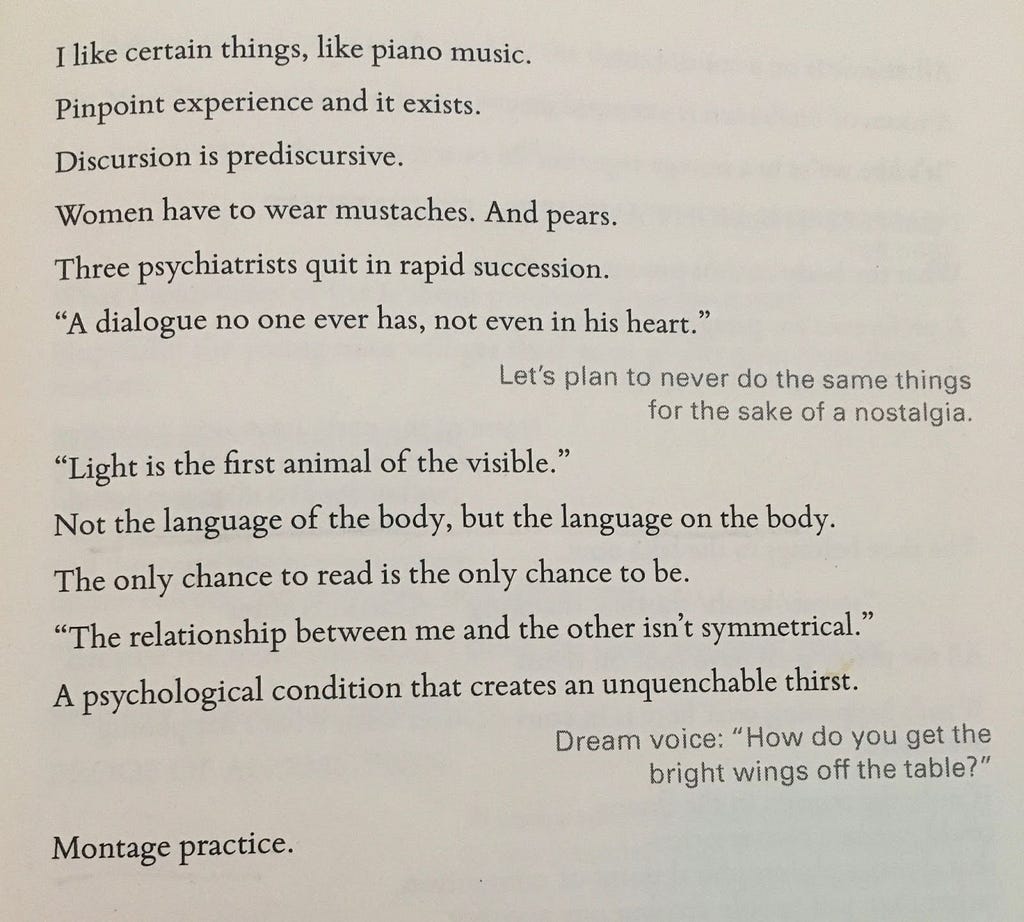

Here’s page 45:

Like most pages in the book, this excerpt is arranged as a polyphonic “field” that fills between half and two thirds of the page. The last line, “Montage practice,” is a compelling description of the book’s accretional logic: colliding selves rehearse for assemblage. The length and position of each line also varies, and even the capitalization on other pages. Each line shifts in its subject matter, resisting coherent narrative. Hunter’s code-switching tone varies from straight-faced and philosophical (“Discursion is prediscursive”), to cheeky absurdities (“Women have to wear mustaches. And pears.”), to “dream voice.” Quotes, from an interview with filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard and a poem by Ana Božičević, add even more voices into the mix.

While hunting down the sources for these decontextualized references is a fascinating exercise in falling down Hunter’s research rabbit holes, the rewards for the reader are plentiful even without leaving the confines of the book. Rhythm, for instance. Many lines here repeat a sound or word, but with always with a twist: “Not the language of the body, but the language on the body. / The only chance to read is the only chance to be.” The repetition is never the same, seemingly following the right-justified advice to “never do the same things / for the sake of nostalgia.”

As you might sense, many lines feel allusive, and in a string they can feel like a long series of inside jokes. Either you get it or you don’t (for the most part, I didn’t–and embraced that), but my sense was this book doesn’t care so much about being understood. Indeed, the book calls into question our sense of understanding anything at all.

But the incongruous meaning-making is also an invitation: as a reader, I have the opportunity to draw connections of my own and latch onto resonances with my own dream/waking lives. Lyn Hejinian’s essay “The Rejection of Closure” feels instructive in its approach to reading as active co-imagining, if you are open to this relation. Hejinian writes that the “open text” is “generative rather than directive. The writer relinquishes total control and challenges authority as a principle and control as a motive.” An open text like Vibratory Milieu makes space for the reader to build their own psychic contexts.

You may not want to read this book linearly from cover to cover. This is a book with many entry-points, without a singular intended route. Turn to any random page and it will feel like you’re walking into another dimension. I enjoyed encountering it as if I was doing contact improv. My attention and comprehension had its ebbs and flows, but I enjoyed watching how the text blocks surged and retreated; I attended to moments of resonance and harmonized in the margins with my own citations and lived history.

Some of Hunter’s lines offer pointers for what to expect as a reader and how to bear witness to the writer’s right to be an unreliable narrator. “MY BODY HAS CHANGED ITS MIND” or “BOUNDARYLESS METAMORPHOSIS’S APPARENT BORDERS” warn me not to be so surprised by sharp turns, contradictions. Or a cagey [read: John Cage-like] line like “how sound is chance” or “DECISION WITHIN APORIA” instruct me to embrace the aleatory, random, and chance encounters with language. Almost like cruising.

It’s hot. Shit, I want to read this book with a vibrator in hand. Not that this book is pornographic, or even particularly sexual in nature. But that the propulsion of this book feels, as the title invokes, vibratory. (Kathy Acker writes about writing while masturbating: “One thing I do is stick a vibrator up my cunt and start writing — writing from the point of orgasm and losing control of the language and seeing what that’s like.” Why not read to the point of relinquished control?) Lines feel charged and the semantic and narrative gaps between them make me feel in between them. It’s like the experience of being shaken, oscillated. Language feels out of control, out of context, out of body. I’m along for a ride.

Speaking In “Dream Voice” was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.