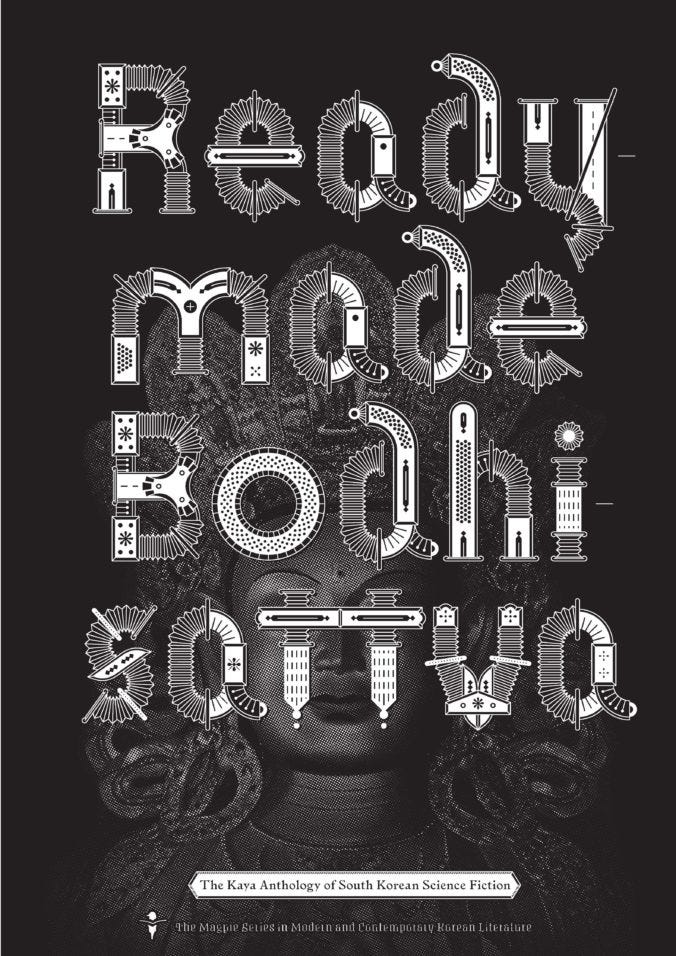

Readymade Bodhisattva: The First Translated South Korean Sci-Fi Anthology

TW: Abuse, suicide.

My favorite science fiction combines tech, action, and a look into new conflicts that could arise, including one’s sense of identity. All of this and more is present in Readymade Bodhisattva, a new short-story anthology from Kaya Press. Even better: it’s the first book-length English translation of sci-fi from South Korea.

Edited by Sunyoung Park and Sang Joon Park, the anthology includes thirteen science fiction stories, ranging from classic stories from the 1960s to present day, that explore the implications of science fiction changes to individual lives. Many of the writers explore political and social changes in their stories, including colonization, feminism, commodification, slavery, and education reform while being a genre relatively new for South Korea. Most of the stories have South Korean political contexts provided in their introductions. These values accompany these writers’ influence in South Korean sci-fi and show how these writers have used and shaped the genre, young to the country.

While there are thirteen stories total packed with layers of conflicts, I was particularly drawn to two’s unique combination that captured the core theme of the stories. “Readymade Bodhisattva” examines the relationship between Buddhist religion and technology. The other is “Between Zero and One,” which addresses issues within education, its treatment in South Korea, and the abuse involved that has been normalized for generations.

The first story in the anthology, “Readymade Bodhisattva” by Park Seonghwani, takes place in a Buddhist temple run by both humans and robots. The robots were purchased to run the temple for human monks. One robot, Inmyeong, was programmed with a measure of self-awareness, He began preaching and claims he’s achieved enlightenment. The president of the robotics company insists Inmyeong should be erased as a threat to humanity arguing that he must be malfunctioning and needs to be repaired despite fulfilling his duties. A Buddhist master declares that declaring Inmyeong as enlightened would turn people away from Buddhism because the robots are said to be created without desire to be able to serve humans. While humans must wrestle with desires over lifetimes to reach enlightenment, robots are born “‘bodhisattva’ for those beings that have transcended such human frailties.” The company president activates a rule requiring robots to follow all commands. Inmyeong instead expresses enlightenment by being able to break free of servitude.

The robots’ expressions of self-awareness are questioned because they are seen as commodities. It’s a tale of influences of corrupt desires — greed and manipulation — in ensuring the robots stay enslaved. It’s also expressing a form of traditional Buddhist story that would be new to many in Western audiences called the jataka following a Buddha through lives towards enlightenment. This one follows Inmyeong as a Buddha achieving enlightenment while being troubled with human desire, including a Buddhst master.

“Between Zero and One” by Kim Bo-Young, asks how a world ruled by probability would work, blending quantum physics and time travel with issues of competitive education and parental abuse. This story alternates perspectives between a mysterious narrator and Mrs. Kim, the mother of a struggling teen named Soo-ae. While the narrator works with a machine that functions off probabilities when doing research, Mrs. Kim is in a neighborhood meeting of mothers just after Soo-ae committed suicide. The mothers alternate between complaining and boasting about their children. The complaints? Slacking and participating in education reform protests. The boasts? Their children foregoing friendship, food, and water to spend as much time as they can studying to meet their parents’ unhealthy and competitive expectations. Mrs. Kim finds conflict between her desires to keep up these norms out of a perceived need to and break away after Soo-ae’s death after her own hand in it. The neighbors continue trying to justify their treatment of their children, including trivializing their complains as Mrs. Kim did and insisting all children are the same. She pressured Soo-ae about studying and her participation in education reform protests. These interactions emphasize the disparity between traditional education goals socially enforced in South Korea and rapid technological advances that make many of those goals obsolete.

Our mysterious narrator approaches Mrs. Kim and initiates a conversation on technology, time travel, and quantum physics. But Mrs. Kim leaves the interaction with the feeling that there’s something wrong with this woman, despite the narrator representing a break with the norms Mrs. Kim now struggles with. She’s unable to recognize her own cognitive dissonance in her desires to break away from the neighborhood meeting and to see Soo-ae again. Meanwhile, the mysterious neighbor is both recognized but distant and unfamiliar despite Mrs. Kim’s wishes.

But, as the narrator says, “No one asks about my story. No one ever asks about me. They say I’m like a phantom, because they can’t quite tell if I really exist.” Not even Mrs. Kim recognizes the narrator during her search for answers differing from her neighbor’s mantras. Even the narrator’s coworkers who built the time machine with her see her in this way. In a sense, the narrator is a phantom. She’s a version of Soo-ae who didn’t commit suicide and was able to pursue her goals. She visits Mrs. Kim after the other Soo-ae’s death both to comfort her and convince her a second chance exists if she’s willing to change and learn. Mrs. Kim begins recognizing the harm in her actions despite her selfishness, but doesn’t move forward the way technology does. She stays within her norms of what the world is. The only character who asks the narrator about herself is young Soo-ae, on the verge of suicide, and it’s with assumptions based on neighborhood rumours. The adult Soo-ae acknowledges the abuse of the time machine with the ongoing presence of archaic beliefs, but also that she only exists because the time machine was created. She acknowledges she had a hand in her own death, the only reason why she’s been able to carry out her inventions and work uninterrupted living as a phantom.

Readymade Bodhisatva is full of philosophical discussion coupled with political messages about identity within the influence of sci-fi. People can’t decide what another person’s identity is without making harmful choices for selfish reasons. Similarly, like the parents in “Between Zero and One,” people can’t insist a collective identity is static and that individuals within these categories are identical without the harm that brings. These broad, sweeping statements have their own specificities and differences unique to the experiences of people in South Korea. The translation of Readymade Bodhisattva means some of South Korea’s cultural identity is spreading so that we can learn and acknowledge it.

Two things are certain. Firstly, the creation and influence of new science fiction will continue and can’t be undone. Secondly, the sharing of these tales for English speakers to enjoy South Korean sci-fi the first time are a welcome and overdue development.

“Readymade Bodhisattva”: The First Translated South Korean Sci-Fi Anthology was originally published in ANMLY on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.