“The Child of Broken Earth”

Maria Esquinca Reviews Karla Cordera’s How To Pull Apart the Earth

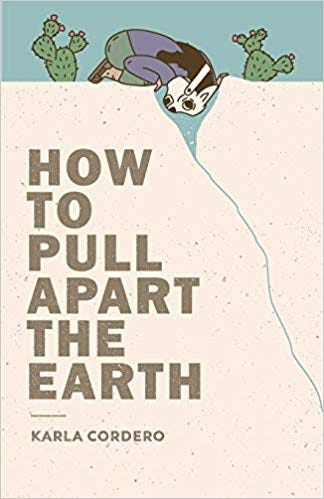

How to Pull Apart the Earth, by Karla Cordera, is a book grounded in the land and the hands that tend to it.

Karla Cordera is a descendant of the Chichimeca peoples from Northern Mexico, a Chicana poet, educator, and activist. Her stunning debut collection is full of lyrical poems, magical realism, and surrealism. The book is divided into four sections that touch upon themes like immigration, language, and ancestry. Threading the book is a continual reference to the land, whether literal or figurative. Cordero’s book rejects a colonial relationship with the land, which is one of consumption and transition. Instead, her project is in constant conversation with the earth.

In “Hija de la Cosecha,” which translates to “Daughter of the Harvest,” we see how the land plays a central role to the speaker’s existence. The land literally becomes its own character, a mother providing sustenance to her “child of mouthful-harvest.”

“here/

the carrots offer their silent bodies

& resurrect when mouths go

hungry. here I savor the wild

blueberry. swirl the sweetness

after each navy pebble pops

between the teeth. i remember i was

i was once the child of broken earth.”

Cordero allows us to see everything the land has to offer. Aside from nourishing the speaker physically, it also nourishes the speaker spiritually. It forms a central part of her identity. It is not separate from the speaker, but rather, the speaker seems to say, I am of this earth.

This intimate relationship with land is also carried through by the people in Cordero’s book, brown immigrants, indigenous people, many of them farmworkers.

Historically, there has been a void in literature where farmworkers should be. Rather than relegating farmers to the background or ignoring them altogether, Cordero holds a magnifying glass to the relationship between land and laborer, often focusing on her own family.

In “His Jawbone Caged My Grandfather’s Skin” she writes: “The same skin on braved bone/ once picked/ apricots on the orchard farm/like delicate newborns.”

Cordero uses images that depict intimacy, delicacy and love to describe farmworkers, paying homage and respect to their labor. In “Driving Down Highway 111” the speaker is observing farmworkers picking lettuce:

“my nose bitters to cow manure/

as lettuce fields pass the car window/

& men who dare to play with such growth/

knife & box the leaves

behind their sweet-licked bandanas”

The speaker continues to talk about the daily lives of the farmworkers: within the poem, they talk about their wives, the food that awaits them at home “broth-boiled rice & cilantro,” and the wall. In a world which omits the daily lives of farmworkers, to speak them into existence is a radical act.

Present through the book is also a reckoning of identity. How is Latinx identity shaped when we come from a lineage of colonized peoples? It is a question that Cordero grapples with in

in “Bisabuela Married a Spaniard.” She asks, “what parts of my bones belong/to the ship/that broke the sea/that broke your tongue.” Present in the poem is the struggle to hold Mexico’s history as a colonized country, and the implications it has for Latinx idenity. What is forgotten? What is erased? What will never be recovered?

“but what does crying mean in this country/ my abuelo sits at the kitchen

table/ fox news spills into the same air/ he labors

to belong in his resistance:/ swatting

the fruit flies/ over a browned apple”

Cordero, moves away from the over-simplication of Latinx identity. In “His Jawbone Caged My Grandfather’s Skin” the speaker’s grandfather is watching Fox news. Such a move brings into the light the ways in which we are complicit with empire. By doing so, Cordero is able to write about Latinx identity in a way that is layered and nuanced.

Since the author is a fronteriza (someone who lives in a border city), it is not surprising that the border also plays a central role in the book. Cordero writes about the American/Mexican borderlands and the effects immigration laws have on fronterizxs. In “Reincarnation” Cordero writes about the unveiling of prototypes for Trump’s border wall in San Diego County: “teaching a country/ how to erase a country/ & a people to learn/ to butterfly over exile/ to be a swarm of bees/ their pollinated backs/ who learn to harpoon the wind.” Even in devastation, Cordero resists victimization and illustrates people who thrive.

Cordero returns to nature to depict survival. In “Leaked Audio from a Detention Center” a poem based on the audio clip released from a detention center of undocumented children crying, Cordero writes “hear how the children/ eat their tears/ how the rain/ in their throats/ demands to be a river.” Cordero finds a way to write images that evoke hope and power. She pierces through the tragedy “grief can be/ a kind of music/ that knows how to rise/ like the sea.”

Politicians often politicize the border as a place of danger and crime. Here, we see Cordero writing a place that is full of strength and hope. But Cordero does not diminish the pain and violence that exists in the borderlands. She exercises a balancing act between pain and survival. “to understand border/is to witness your home shrink,” she continues “be forced to split it/with a machete/ & surrender a slice.” However, we also see a community that rises. “but we too/will burst back/an orchard/knotting our bare foot/rooted to the land.”

Cordero paints a picture of the border, one that is complex and multifaceted. It is not a border that is pathologized but rather a portrait written through the people of the border.

How to Pull Apart the Earth is a lesson on collectivity. It is a book in community. It does not speak to itself, or at itself, but rather at the different strands that makes us who we are. It is a book that is able to look at people fully. It is a lesson on resistance.

Maria Esquinca Post was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.