“Not everyone’s story ignites in the social world of formal schooling.”

— Various Men Who Knew Us as Girls by Cris Mazza

In order to embark, as so many of these narratives do, in graduate school, this narrative has to launch in the middle. We can agree the beginning of a narrative isn’t always the ignition of the story. In these explorations, that moment we may never find. My best shot will be to look [as] simultaneously [as possible] backwards and forward from the middle, examining more various men who missed the cut when the narrative was a novel.

— Cris Mazza

The friendship started because we were both from California. After that, and our ambitions to write fiction, and our relative ages, there wasn’t much similarly between us. Except our genders. She sought me out as a potential compatriot when we entered the graduate program, and I, a habitual wallflower, was grateful she did. More like a wall-weed, because there wasn’t much about me beautiful to the senses of sweet-seeking insects nor human males. I was pretty sure of that, and that I’d already managed to locate the only one on earth who saw my androgyny as an appropriate package-deal with the whole person.

A significant difference between me and my one friend in this venture of graduate work was revealed to me in the genial east coast weather and evening light of September, when she urged me to accompany her after class for “drinks” with the professor of our folklore seminar. How long did it take me to realize the professor had asked her, and she’d dragged me along as a shield? More than a minute, less than an hour.

My friend — from here on Student-A — may have had a few additional invitations from the folklore professor. He disappears now; he is not Professor-A, one of our mentors in the writing program who would guide our work and development.

He was her graduate advisor. I don’t know what he advised her in. He read her poems, analyzed her paintings, critiqued her plays, studied her clothing designs, discussed her photography technique, suggested good books and movies, played her songs on his piano?

And he started calling her and visiting her in her windy one-room apartment where she served herb tea that tasted like dirt or perfume…

— “Former Virgin” by Cris Mazza

See, I’ve written about this, all these things, before. Never quite satisfying the need to solidify some kind of conclusion.

At some point, I became aware of the special connection between Student-A and Professor-A. Special: exclusive, private, superior, unique. I could have chosen any of these words. And at the time, the early/mid 1980s, I did. I chose all of them, and more. As well as their antonyms that must therefore apply to me: not special (unnoteworthy), not interesting (mundane), doesn’t stand out [in this cluster of other burgeoning writers].

Professor-A seemed distracted in our one-on-one tutorial sessions, seemed to have not read my work thoroughly, made remarks that — when I inquired why or how — he then backed away from, only to not be able to replace the first observation with another. I remember a specific frustrating session when his greater interests/fascinations/enthusiasms/stimulations — that is, Student-A — were squarely in my consciousness as to blame. So I wasn’t just sensing a disinterested professor, I was reminding myself what caused it.

Wasn’t a professor who was energized by what you had to offer, your talent, your execution, your particular way of expressing your perception — wasn’t he a crucial cog in your eventual success? Might he not be a key figure in that thing called “connections?” I had heard all about “being at the right parties,” and dreaded ever having to make the choice, go or stay-home, if/when I ever received the crucial/ alarming invitation, because I knew the tug of stay-home would easily win. So my whirring thoughts about Professor-A’s attentiveness to Student-A might have also noticed that she would not have as much need for the chaos of those “necessary” (and elusive) parties, for which the invitations never came.

Basically, my worth / value / potential to succeed as a writer was being put into question by my not earning the most or “best” attention from the professors. I immediately concluded this situation involving Student-A meant I must not be as interesting or talented.

In order to succeed, I’m going to have to get their attention …

But I did not think: I’d better get sexual attention from my professors/mentors in order to succeed. That is, my thoughts made no conscious link. The suggestion of that link was there anyway: any attention meant my potential as a writer would be included. So “that kind of attention” did help; it was snarled up with the need for validation of potential and merit. And [any] attention was needed to boost my immergence into a career because I was completely without the ability to “go to the right parties,” which, essentially, meant the same thing. In more ways than one.

The convergence of these unrelated notions might have been bolstered by the fact that this was no Barbie-gets-all-the-breaks. If so, if I had been seeing a “classically” beautiful (i.e. fashion model) young woman get the “best” attention of the male professors, I might have made different (subconscious) conclusions, including a gross assumption that that kind of beauty came with an airhead (a common cultural prejudice in the 80s). Student-A was not conventionally “pretty,” and wasn’t particularly well-endowed in her bra size, but was enormously well-read and informed in off-the-beaten-path philosophies, culture and literature. Before entering the program she had (for reasons I never bothered to ask) shaved her head, so her hair was growing in, a soft half inch when we met. She preferred to wear her sweaters backwards, sometimes inside-out. She carried an oiled parasol instead of an umbrella. One of her outfits was a black military parachutist’s jacket worn like a dress over black tights. Her wide mouth, always with red lipstick, could produce an entrancing smile (note: I don’t use the words beguiling, alluring or enticing. Her smile may have been all of these, but that would suggest she was “prowling” for the attention. I can’t say that she was or wasn’t.) Her voice was quiet, sincere, her laugh piping but gentle, comfortable. The exact opposite of the current in-vogue vocal-fry.

Student-A was awarded the outstanding student designation in our cohort, despite her record still bearing an incomplete in a literature course. Perhaps she had written a brilliant comprehensive exam; I’m sure mine was basically adequate. Within a year following our graduation, her thesis novel was accepted for publication by the independent press co-run by Professor-A. To this date, Student-A has not published another book. This may have something or everything to do with the aftermath of her “situation” with Professor-A, but that is her story to tell. My story has to do with the ripple-effect of her experience with Professor-A on those others in her sphere, or at least me. As well as I can remember, the amorous attention given her only proved, to me, she must be more interesting, deeper, more substantial as a writer. Driven, ambitious, and, yes, competitive (a way of measuring my “success”), I left that place with acute disappointment, which I could only direct at myself for not being profound enough.

So I did equate Student-A’s magnetism — evidenced with more than one professor — as a positive indicator of her worth that must include her ideas and writing. Therefore, the equation attention = potential = deserved career-boost (her book publication) was throwing its shadow onto my path as a writer … including that my worth/value as a writer was integrated with my worth / value as a female?

But, really, that “equivalence” hadn’t started there, in my 20s, at a writing program.

How often, in how many essays, do I have to use this Erica Jong quote: Growing up female in America, what a liability.

We already know how advertising bombarded us with what was required to be attractive, to be desirable, to manage to not end up alone, a state in which a woman was “unfulfilled” as well as precarious. Putting aside the still-almost-absolute condition of inequality that persisted when I finished high school and began college, that I had exactly one female professor as an undergraduate, that we read exactly zero female novelists in high school, it was a small miracle that I didn’t have a notion that I shouldn’t be pursuing the course I was on, toward calling myself a novelist. Of course that path had started with journalism, veered into secondary teaching, and, having vacated both of those, went (back) to the only thing I knew I could do. And was wholly encouraged by male mentors and professors. How I may have subliminally thought I didn’t fit, however, shows up, in hindsight, in the first fiction (if you can forgive the clichés) I wrote as an undergrad, and the first where the main character was not male:

When most people think of a female star, they expect, and usually see Miss America walk onto the stage or screen; a blond-haired five-foot-eight beauty with legs that start at her shoulders. She’d have blue eyes, daintily sculptured cheekbones, a small thin chin, a cute pug nose, and a sweet red mouth which never says anything wrong, but never really says anything smart either. If that was a “star” I was either a mistake or an exception… [T]hey would see a five-foot Italian with a short mop of hair and brown eyes which aren’t dark enough to look like a foreign beauty, but are more the color of dirty water. I have glasses I don’t like to wear, thick eyebrows I don’t like to pluck, and fairly short limbs which don’t move with liquid agility …

— Cris Mazza, 19 years old

Ideas present: I was not beautiful, but an odd-looking girl could have talent and substance that made her of value; and that pretty girls were hollow, devoid of idea, their talent only to be beautiful. “Don’t hate me because I’m beautiful,” they begged in advertising, tired of unfair assumptions like mine. I didn’t hate them. I thought I was rising above what they had to offer.

After all, in junior high, I’d been told by “cool boys,” that I “had nothing to offer.” That didn’t prevent two other boys from trying to find something, as they pursued me in and among the deserted auditorium curtains (where we were supposed to be practicing our violas and cello), pinned me immobile so they could grasp and feel parts of my body that might have been changing. And I, not yet “the mistake or exception” in my college novella, actually thought they like me. Maybe those cool boys were wrong, I did have something to offer. Thus, although I was trying to escape them, I’d gotten culture’s message. I never told a teacher or simply left the backstage area for sanctity of a restroom.

It’s thought that girls get the message as young as the toddler stage. In one recent study, ‘We found that fathers are using more language about the body with girls than with boys, and the differences appear with children who are just one to three years old,’ said Jennifer Mascaro, [assistant professor of family and preventive medicine at Emory University]. [Parents] with daughters … used … words …, such as ‘belly,’ ‘cheek,’ ‘face,’ ‘fat’ and ‘feet,’ and the scientists raised the possibility of a link between these innocent interactions and body image problems that are far more common in adolescent girls than boys.” (Hannah Devlin, www.theguardian.com, 2017).

Another “study … has revealed that half of girls feel stifled by gender stereotyping, with children as young as seven believing they are valued more for their appearance than for their achievements or character. … Furthermore, constraining stereotypes have a negative impact on girls’ mental health, convincing them first that an ever more demanding paradigm of physical ‘perfection’ must be met with apparent effortlessness and then that being ‘popular’ — meek yet sociable — sexy but not ‘slutty,’ sporty in a narrow, feminine parameter (not ‘too muscular’) are imperatives.” (Natasha Devon, www.theguardian.com, 2017).

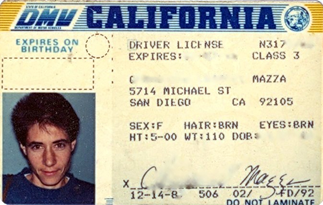

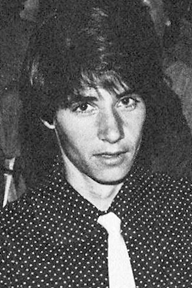

It’s not possible to know what my parents said about my body, and while it’s true my mother dressed me like this (1), she also dressed me like this (2) and I started high school (the year dress codes were eliminated) dressed like this (3).

It’s not a stretch, though, to see that if girls are made aware of the importance of being pretty, they’re also aware of the “rewards” when they “succeed.” Attention. They like me.

From academic to tabloid sources, spanning ten years, some seem willing to look at this possibility without flinching (too much):

“…my experience is that some young women come from familial, social, and economic environments where this is the way women relate to men; if they have a request, they ‘use their bodies’ as Ruby Payne states in her book on generational poverty. These female students may have grown up learning that the way they behave is how women are supposed to behave toward men, even ones older than they, and there is a chance they may not even be aware how their behavior is perceived.” (Anonymous, Chronicle of Higher Education forum, 2006).

“I’ve always dressed with the express intention to please and gratify my male bosses in the workplace. … I am university educated, reasonably intelligent and, so I’ve been told, attractive. … I use it to my advantage every single day. Before you roll your eyes in disgust … consider this. By the age of 30 I had … a generous six-figure salary and a high-ranking position in my chosen industry.” (Samantha Brick www.dailymail, 2011).

“If she’s beautiful, a new study says, there is often a hidden selfish streak. She’s lucky and she knows it, and she will consciously — or subconsciously — use her looks to her advantage any way she can.” (Dale Archer M.D. Psychology Today, 2012).

“I find running a business in a man’s world to be a huge advantage. I wear bright colors, yank up my skirt + get attention… When I was building my business, I would walk into a room of 600 men … and I dress like a guy in a nice pant suit, no one would say hi to me no one would entertain me. The minute I started wearing bright suits and have a nice length skirt on, I would just roll up … into that room, everyone paid attention to me.” (Barbara Corcoran, Access Hollywood, 2016).

Heresy. But I have to admit: I’ve had this opinion about certain women I’ve encountered. Just not about Student-A. And not about myself, a few years later, when I —

First, moving backwards chronologically, who was the person who went east for graduate work and had a ringside seat for Professor-A’s habitual (it turns out) behavior?

The first graduate degree, conferred mere months before I went east for the second: my committee was three men. (West coast professors will be named numerically. Only Professor-1 and -2 will appear here. The third, my actual writing-mentor, was an obscure experimentalist, one of the first graduates of Iowa, who did nothing but show me how my fiction worked, was the one to direct me to the 2nd grad program, and whose last words to me, in the late-80s, were don’t quit).

Professor-2, already relentlessly dissected in most of my fiction for reasons beyond this topic — and despite our relationship being all dialogue, occasionally written, often theoretical even when about emotions, or even sex — is not a non-player here. For reasons I don’t remember, he told me a story about someone he knew or had known, a Professor of music, who “grabbed a girl after class and physically told her how he felt. They were married in about three months.”

I wrote it down, word-for-word, in my college-era journal the same day it happened, so, shaped only by my youthfully-sharp short-term memory but emotionally-teeming adolescent-perspective at the time, our dialogue after the story went like this:

Me: She fell for that?

Him: I guess she felt the same way, was waiting or hoping he would do that.”

Me (wanting to remain skeptical): Still …

Him: She kicked him out three years later. He grabbed another girl in another class, and she — his wife — didn’t like that. He said he should have that right, to follow honest impulses.

Me: And he had a double-standard?

Him: Maybe. He said he didn’t. He said she could do the same. She just didn’t want to. Her father —

Me: If she was brought up like that, why wouldn’t she be scared when he first grabbed her?

Him: She probably was, but she liked it. She might have been hoping for it. If she didn’t know those impulses by then …

Implied (and heard by me): …something’s wrong with her.

Classic predator behavior, narrated to me as “honest impulses,” “telling her how he felt,” “she liked it.” Need this be picked apart any further?

During this same time, I participated in a drama-department production of Cabaret, as a member of the all-girl band. Connoisseurs of Cabaret remember that the all-girl band is usually portrayed as men in drag. Not a casting requirement because only men can play the music — it was part of the depiction/characterization of the time/place milieu. But our director thought it would be interesting to have the band actually be all girls, dressed as sexy (or in this case whorey) as possible. At the time I thought his “update” was innovative. Now I think having men in drag on stage at a public university might have caused too much controversy.

As a girl who played trombone, no longer unique but still unusual, I was recruited for the all-girl band. So the graduate-student writer by day looked like this, and at night like this (amateurish stage make-up self-applied).

Professor-1 came to a performance. I do recall telling him beforehand about my participation. I do not recall if I supplied his tickets. If there were free guest tickets to cast members, wouldn’t my parents have gotten those? Why is this important? If there was an invitation from me, vs. if attending was his initiative, it seems significant.

Afterward, the next time I saw Professor-1, he said, “Cris … wow … I never would’ve thought… There’s a whole other side to the quiet girl who never said anything in class. I mean, really, Cris…”

I thought it good to have an “other” side to background-Cris. After all, I’d performed the Cabaret music on stage, live. I was proud of that.

We’ll return to Professor-1 later. A step further back, and I’m in my secondary-education program finishing a teaching credential in English which, like the journalism degree before it, I abandoned. Explored at length in two novels, this is where I encountered the textbook case of powerful-male-mentor-sexual-harassment. Except for two things: (a) Title IX existed but sexual harassment had not yet been identified by an appeals court, and (b) I was devastated when his frank, overt but pre-sexual-contact attention was withdrawn (I’m sure he was warned that others were “watching”). It was not, however, the progressing-then-withdrawn sexual attention that made me unable to be a high school teacher (one definition of sexual harassment). Perhaps the sexual attention had made me care less about it? But I wonder how anything could have made me feel more anxious, depressed and desperate over the prospect of having to teach high school? I was demoralized over the end of the attention from my supervising teacher. It amounted to: what’s wrong with me?

Was that ground-zero for my take on how sex should play in my future-career or achievements? I could continue to move chronologically backwards, through androgynous wallflower teen years interlaced with instances of sexual discrimination hidden in plain sight. There were other boys who (with my consent) used my body to “practice” before they felt-up their first girlfriends (and, again: he likes me). There was believing when I was told by a man with his hand up my shirt that there was something wrong with me for not wanting “more,” when I didn’t even “want” that from him either.

Yet the other significant alteration in my development during the grad-school era was that, six months before going east, I got married. Seems an incongruity in this self-depiction. But the foreshadow appears in my first paragraph: the only one on earth who saw my androgyny as an appropriate package-deal with the whole person (since then proven untrue). With him I lost my physical virginity, although not to great sensual or ecstatic fanfare.

Being newly married, albeit with the groom still in California, might have been anybody’s explanation as to why the professors didn’t “choose” me. Or anybody’s but mine. My conclusion was that I wasn’t interesting or smart enough. Being not-smart had already been implied by my ‘B’ in literary theory, which I discovered only later was a mark of shame, infamy. And being uninteresting would be a direct comment on my writing. These two characteristics together could certainly render me invisible to those whose jobs might be to discover and nurture writing talent.

Twenty-four years old, questionable as to whether the brain had finished developing. Questionable as to whether it ever does. Or if what passed for development had been inexorably distorted by culture. He likes me: attention = potential.

When I heard this story a few weeks ago, I wished I could tell you about it. I don’t know why. A guy named Roger told me the story about himself and someone named Wanda, but I didn’t tell him about you. He might’ve asked why I don’t see you anymore, and what could I have said, that I cried too much?

— “Former Virgin” by Cris Mazza

Before I follow that duped and disappointed girl into her post-graduate-school future, I need to pause in the present; okay, a month ago: I ran into another graduate of my eastern alma mater; she — Student-C — came to a reading where, by sheer happenstance, I read “Former Virgin,” which I’d written 30+ years ago and had been incited by disillusionment over Professor-A’s conduct, although in the story I made the professor’s interest in his student profound and the student’s reaction coolly detached; his was the disappointment. (I’m sure my alterations to the story can be psychologically sussed-out. I had the professor telling the story to an even more desolate female character with her own parallel story).

After a while I said to Roger, “How about if someone told you you’re not the center of the universe to anyone but yourself,” even though you looked at me and smiled, your words spoken so softly, and the background was a dying day.

— “Former Virgin” by Cris Mazza

Student-C and I had not been in the same cohort. She followed me by a few years. But I asked her if she recognized Professor-A in the story I’d read. Because of my fictionally flipping the disorientation onto him, she had not made a connection. After my brief summary of what I’d observed as a grad student, she said, “He did the same with Student-B, and it really messed her up for a long time. Mine was with Professor-B, but I never wanted to talk about it, bring it up in this current moment, because … well, I know how I acted.”

Sometimes connections are only made by zig-zagging through time, so backwards again to the 80s, after I’d returned to California with my degree and my discouragement and my determination.

Student-A’s thesis novel was scheduled for publication at the press housed at our alma mater. Production time was lengthy so her book had not yet appeared when my thesis won a major award for an unpublished fiction manuscript. The prize was money but did not include publication of the winning manuscript. But the awards ceremony would have to be one of “all the right parties,” and by virtue of being there to accept an award, being noticed would be failsafe, I wouldn’t be responsible for making myself visible. I used some of the prize money to fly east again, even knowing how sick I got on airplanes and how the nausea could linger for days afterward.

Student-A housed me during my short stay, and Professors-A and B arranged to meet me for a meal while I was there. Had they expressed pleasure over a recent graduate winning this award? I assume so. So much about that short reunion was lost to the haze of queasiness. But what remains, what I do remember, has related relevance. First, looking like this, feeling the way I looked, still did not prevent one of the three judges — the only one I’d never heard of — to ask me if I’d like to go for a drink after the ceremony’s reception. Here it was, being at the “right party,” making a “connection,” my fateful moment. But how could I drink or eat anything the way my stomach still roiled. I didn’t go. If there was a thought beyond that, it doesn’t remain. (Maybe if I’d heard of him … maybe my ignorance saved me).

The second pertinent memory from the award-acceptance trip should have been another piece to the puzzle, to constructing some kind of perception that might have spared me my jarring choices a few years later. By virtue of the award given my novel manuscript, Professor-A arranged a meeting between me and his agent. I assumed he knew the day and time of that meeting, but perhaps it wasn’t important enough for him to keep track of. I don’t even remember if I ever had any kind of working relationship with his agent, or if she was one of a long list to ask to see the award-winning manuscript, only to tell me it wasn’t commercially viable. In fact, this is all I remember about my meeting with her: the phone rang and she took the call. Somehow she informed me it was Professor-A. With me still seated across her desk, she accepted a date with Professor-A to attend a professional tennis event. Maybe another area of ignorance: I didn’t realize that while it could go visa-versa, authors don’t usually invite their agents on social outings. I went back to where I was staying with Student-A and in the course of the early evening, while recounting my day’s activity, I told her about the phone call that had interrupted my meeting. I don’t remember what she said or what dialogue we had following the disclosure. I don’t think I intended to be a shitster — stirring up trouble with an unsolicited offering of private information. But I do recall that after I was tucked into sheets on her futon, I could hear her howling anguish behind the partition of her bedroom.

The only “realization” I carried home from my award-acceptance trip, besides passing up an invitation to “make connections,” was that the relationship between Professor-A and Student-A must have still been continuing, but probably would not (and did not) continue after my visit. Student-A, while eventually successful as an editor, never published another book. But it was too soon, then, to know that.

So I continued on in the wake of the award, being rejected by every corporate publisher who asked to see the winning manuscript, as unenlightened as I’d ever been. Student-A’s book was published. In another year my award-winning manuscript was rejected by that same independent press — the one with Professor-A’s indelible fingerprints. And here’s a bit of lingering ignorance: it just occurred to me, my inadvertent intervention in the situation with Professor-A, his agent, and Student-A is perhaps also what stopped any arrangement between me and the agent, and ended my book’s chance with that press.

Among the things I didn’t know or hadn’t become aware of at the time the “award-winning novel” was being rejected: In less than ten years I would be an assistant professor listening to senior (male) professors speak cynically (but was the irony veiled wistfulness?) about the era (60s-70s) when well-known (male) writers were frequent esteemed-guests at other universities and always expected to be granted access to coeds who might want to be impressed by their greatness. I didn’t know that on one visit to my west coast alma mater, a visiting writer chased one of my peers — his assigned chauffeur — around her sofa, after he’d convinced her to take him to her apartment to “rest” before his reading. And who was the hosting-professor for the writers who had visited my west-coast university and provided the student-escort? Professor-1, from my committee of mentors, from the audience of Cabaret.

I learned this before, I already know the type: he’ll be remote, cool, distant — seeming to be gentle and tolerant but actually cruelly indifferent. It’ll be great fun for him to be aloof or preoccupied when someone is in love with him, genuflecting, practically prostrating herself. If he doesn’t respond, she can’t say he hurt her, she never got close enough. He’ll go on a weekend ski trip with his friends. She’ll do calisthenics, wash her hair, shave her legs, and wait for Monday. Well, not this time, no sir.

— “Is It Sexual Harassment Yet?” by Cris Mazza

In the few years after my manuscript won its award, when I found myself mentor-less for the first time in a decade, I turned to Professor-1 in an attempt to have him (re)fill that role. During this time, he told me a story, and likely gave me sketchy details at best, about a female grad student who’d been hounding him. I don’t think he used the word stalking. I do believe the university did somehow become involved in an official way and that he may have had “administrative leave” for a semester. I surmise all that because the story he told me became the fodder for one of my most notable stories — at least the most acclaimed title — “Is It Sexual Harassment Yet?” finished in 1988. I am 100% positive I “allowed” (actually invited) him to read the story when it was in a late draft; I believe the last changes I made to the story, to further confuse whether the she-said or the he-said was more credible, were done after I — .

Later that year she would sit naked in a hot tub — at a former downtown motel remodeled to rent out dayrooms with saunas and Jacuzzis — beside a supervisor from the bank. She kept washing her mouth out with the chlorinated water between the times she went down on him, because there wasn’t a lot of information on whether oral sex was safe. She wanted to be promoted from teller.

— “Change the World” by Cris Mazza

It’s almost as though I don’t know how to begin to narrate this. Only used once in my work (above), and stated that concisely, that one-dimensionally.

It wasn’t quid-pro-quo, A-for-a-lay. It was a desperate need to be interesting enough … to Professor-1. Interesting enough that he would take note of my work, include my work in any of the books of criticism and interviews-with-contemporary-writers he was having published at the time. If not that, perhaps he’d talk to someone with influence at a major literary journal. My name would come up because my work was different, cutting-edge, provocative. And, in fact, my fiction had become infused with graphic, sometimes deviant sexual scenes (the above minimalist quote is from long after that). There were other psychological (compensating for reality) reasons for my seeking the mantle of fearlessly sexual in my writing. But Professor-1’s proclivity for such writing (which I learned later had an aberration of his own), his use of like books and writers in class, his choice of them for his interviews with contemporary writers, could not have had no effect on my writing, from the time I was an undergrad to those years just after my second graduate degree and the sack of warped perceptions I’d carried home and added to the others I’d been hoarding.

My award-winning manuscript was foundering in the submission-cycle. I was immersed in writing the stories that would eventually make up the collection Is It Sexual Harassment Yet? I was audaciously asking him to read manuscripts because I still couldn’t tell when a draft was finished. I would walk to his house to deliver pages through the mail slot. And when he made time to talk to me, I went to his house, or to a bar where he facetiously held office-hours.

I think I recall the sly way he said he had an idea for me. Did he say I needed to loosen up? Or did he just suggest it was something I needed? Why do I want to remember the word need? He might’ve said it if my fiction was prim and cool. Maybe he sensed the pretense in my sexual writing. If so, no one else ever would.

Whatever the reason, his idea was that we would go to a place near that bar where an old motel had been converted into sauna and spa rooms for rent by the hour. He knew I was married. So was he. He knew I knew his wife. Somehow, just like at my east coast alma mater, this didn’t have anything to do with wedlock.

Professor-1 supplied the encounter with cocaine and pot. Maybe if I’d opted for the coke, I’d have a whole different memory and perspective on the scene, which I can only describe with words like mortification, humiliation, degradation …

This was maybe 6 to 8 years after AIDS hit the scene — and “bathhouses” had early-on been spotlighted as part of the problem. That, and my knowledge of Professor-1’s possible peccadillos, plus my well-underway sexual dysfunction… there wasn’t much chance the marijuana was going to break through to rid me of inhibition: At any time I could have said, wait, no, I’ve changed my mind.

But had I changed my mind, despite feelings of odium, shame, disgust … picturing myself an orange segment turned inside out with a grunting, writhing creature scouring away at the pulp with his teeth and tongue (an enduring image likely supplied by the pot)?

Besides, was it fair to change my mind after “my turn” on a hard, wet bench in the sauna portion of the cubicle? Wordlessly (really?) we shifted into the hot tub for his shot. That’s when I tried to sterilize my mouth with the chlorinated tub water, trusting that this seedy place would have bothered to maintain disinfected water, even knowing that it would only possibly be antibiotic, not an antiviral, and no HIV prophylactic had been developed except condoms. He never suggested or produced one.

Oral sex had long been my tactic to compensate for my sexual dysfunction which made intercourse painful and fruitless (for both parties). But that day I made up for nothing with nothing. Was it his use of cocaine? My obvious lack of “response?” My mouth-washing-out “technique?” It seemed to last forever, but it was never finished. Eventually, somehow, and without saying as much, we simultaneously gave up. It must have been me stopping. And him, likely embarrassed, might have said thank you. Trying to recreate it in this amount of detail feels grisly. So I’ll stop here, too, without climax.

It’s no story denouement that, although I have a vague memory that he did perform an interview with me, the interview remained on cassette tape, never published, never even transcribed. I wonder what I had to say.

And where does this fit in the current picture emerging from the shadows — in particular in the world where my career exists — of men, mentors of young writers in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, exposed as pillagers of naïve young woman? It’s the brand of naiveté that is more problematic than one might assume. Especially as Title IX became stronger and sexual harassment was court-defined and tested (after most of my experiences). Weren’t these predators sensing some skewed implicit notions on our parts? Not just a “weak” female’s longing for “love,” but a distorted, even deranged definition of our comprehensive value thrust at us, which somehow we bought. What I witnessed happening during my grad-school experience in the east, what I’d serendipitously dodged at the award-ceremony when I was too airsick to “capitalize” on-a-go-out-for-drinks connection … I returned home and chose: In order for him to respect my work, first he had to like me.

I had to have something to offer.

Cris Mazza’s new novel, Yet to Come, will be from BlazeVox Books. Mazza has eighteen other titles of fiction and literary nonfiction including Charlatan: New and Selected Stories, chronicling twenty years of short-fiction publications; Something Wrong With Her, a real-time memoir; her first novel How to Leave a Country, which won the PEN/Nelson Algren Award for book-length fiction; and the critically acclaimed Is It Sexual Harassment Yet? She is a native of Southern California and is a professor in and director of the Program for Writers at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Nothing to Offer was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.