I’m not trying to accuse you of anything, but Allie Wittner might be. The first-time playwright of Charlie Boyd had audiences laughing and moved to rapt silence throughout her play, performed in early August as part of the She LA Arts Summer Theater Festival.

Wittner, who also stars in the play, crafted a tragicomedy with a story line too many of us will be able to relate to. Charlie Boyd begins with Wendy (Wittner) lying on the floor of her mother’s living room, scrolling through her Instagram feed. She’s just been broken up with by her girlfriend, Liza. Seeing Liza around her college campus with another woman — “wearing my clogs” — is too much for her. So, she’s home.

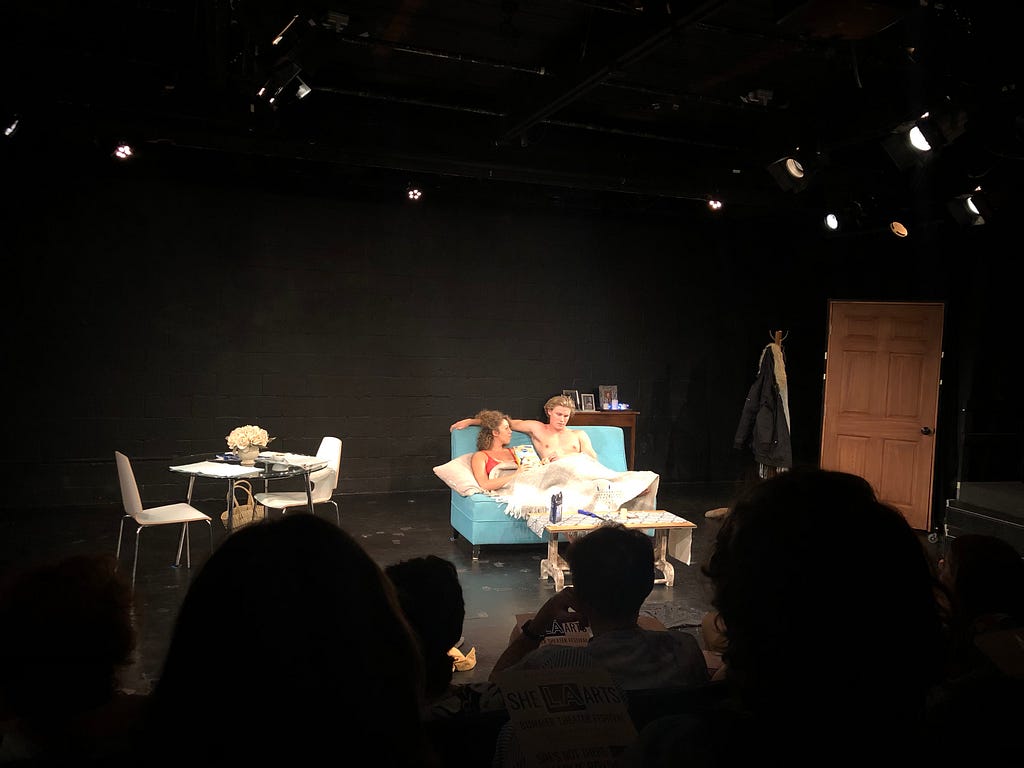

The first few acts of the play proceed in a Shakespearean fashion — romance is center, the banter is witty, and the trajectory seems clear enough. Wendy’s mom, Jill (Mary McBride), tells her that Charlie (Jackie Kay) is also back in town from school. The two (predictably) meet up and swiftly fall into bed together. Charlie was Wendy’s high school crush.

He tells her he’d thought she was cool; maybe too cool for him — she’d been smart, always starting petitions, philosophical. She tells him that during physics class, she would leave to go pick her blackheads in the adjacent bathroom. Charlie claims to be a romantic, regaling Wendy with the soppy, overblown speech she “should have” given him in high school.

But these progressions towards romance are foiled by a local high school self-styled “journalist,” Frank (Magi Calcagne). Frank is supposed to be engaged in a project about Jill (Wendy’s mom) centered on her experience celebrating Hanukkah as a “single, empty-nester.” Instead, Frank reveals to Wendy that there’s a woman in Charlie’s recent past who has accused Charlie of some rather unromantic acts: shouting, making violent threats. (In response to these accusations, Charlie shouts and gets angry at Frank.)

This is the crux of the play, where Wittner thwarts audience expectations (age-old and tired: love! marriage! the family unit!) and begins to implicate us all. The question becomes: Will Wendy believe the woman’s accusations against Charlie, or will she believe Charlie’s well-worn tale of innocence? As someone who has been political, is a member of a religious minority, and is a daughter raised in matriarchy after her father left, will Wendy choose complicity with the cause of so much gendered suffering or solidarity with this unknown woman? Wendy’s line of site at the end of the play, eyes wide, focus centered on the audience, is an implicating move. In this choreography of the gaze, Wittner is begging the question: How many of you have chosen to believe the offender?

I don’t want to give away too much more, because I hope this play will have further showings, and that you will all attend. Wittner is a promising writer, obviously interested in the foremost issues of our era, and equipped to inspire thought without resorting to polemics. Hers is a career to watch.

We Are All Complicit was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.