On Becoming Prey: A Conversation With Jeanann Verlee & Genevieve Pfeiffer

Genevieve Pfeiffer: You write about violence, and pain. One poem, in particular, “A Good Life” stayed with me so that I had to come back to it over and over again. Emotions, experiences, healing — these things can be cyclical and we will come up against certain pains over and over in life. This poem does a heartbreaking job of showing the reader a life haunted, not entirely shaped but influenced by, an act of violence that occurred when the character was a child. It also depicts how pain can be passed from one to another, how humans react to pain and in turn cause pain in others.

We each have our own ways of processing pain and violence. How do you manage pain? How have the ways you’ve dealt with pain changed throughout your life?

Jeananne Verlee: To your first question, I write. I’ve long processed my pain through poems and stories. I tell and retell. I reimagine. Sometimes I execute vengeance. Sometimes I take accountability. Sometimes an abusive ex becomes a bison. Sometimes I stitch myself into a suit made of lambskin. Anything is possible on the page. Even, if we’re lucky, healing.

As to the second question, I’ve struggled through many tactics to manage pain. From drugs and alcohol to self-harm to sex to therapy and medication. Therapy has helped shape a stronger self and procured much healthier methods of navigating suffering. But I know — as a person living with bipolar disorder, PTSD, chronic anxiety, and an autoimmune disorder — my methods are prone to waffle. I do my best. Every day is new and I am continually working. I self-interrogate in effort to ensure my reactions are appropriately directed. I want always to avoid misplaced outlash. I am no longer invested in self-harm in its many forms. I am vigilant about protecting my solitude, and I no longer over-promise myself or my skills unless I am compensated. I am still working out the kinks in how best to manage my physical health and rebuild my immune system, and that drags on my psyche sometimes. But age has gifted me hindsight. I can more easily recognize warning signs and am more aware of my learned trauma responses, better aware of the rationale behind fight/flight/freeze/fawn. All of which I have enacted throughout my time on earth.

GP: Your writing is an act of resistance. What advice might you give to writers who are grappling with the urge to write, but have difficulty finding words to give to their experiences? You also have many approaches — you mix narrative with other points of view, you draw from fantasy/phantasy; you write of many species while simultaneously throwing the human against a stark backdrop; and hold space to recognize the intimate intricacies between violence, sex, and many types of love — all this while asserting that violence as unacceptable, and holding accountability sometimes in a gentle way, sometimes in a deeply angry and pained way. What advice might you offer writers when dealing with this intimate, painful, and deeply necessary shadow work?

JV: I suppose the two questions lead me to similar answers.

I experiment with various ways to access each poem/story. I would suggest the following as entry points for others stifled by the weight of their content:

- Play with POV. I often use second person when I need to unlock a truth I am too embarrassed or ashamed or uncomfortable to say outright. Later if/when I grow more comfortable with the subject, I edit the POV.

- Try fantasy/surrealism/magical realism. Turn your abuser into a bulldozer or Jupiter’s farthest moon. Make machetes of your hands. Give your youngest sibling a superpower. Give trees a language. Writing your truth in fantastical ways that render it nearly unrecognizable can serve multiple purposes: 1) you allow yourself to exercise the muscle of invention, 2) you build a safety net between reality and those you don’t want to expose (lovers, family, abusers, colleagues, etc.) for any reason, 3) you protect your own precious vulnerability — which can be supremely important for those navigating trauma.

- Shift genre. My primary genre is poetry. I think and process trauma in poetic languages and imagery. I struggle to write emotional vulnerability in prose, and tend to use that for critical social and political analysis. But sometimes it helps to shift, leave poetic device aside to just to “get the story out.”

I’m honored by your phrasing, “act of resistance.” While I don’t see my work in that way, and certainly don’t sit to write with that in mind, I know my own stories and I know there is something revealing and relieving in having come through many of them with a fresh approach to living. I’m here and that feels good.

I know also that anger is a facilitating emotion. We — women in particular — are raised socially to contain our anger, to mute it, hide it. Anyone guilty of showing anger is labeled derogatorily and our rage dismissed, typically conflated by some offhanded questioning of our psychological health. This shaming of our rightful rage often manifests in prolonged nurturing of those relationships that don’t serve us. We continue along, oscillating between the desire to fulfill the expectation to nurture and the need to express valid rage. I am only able to facilitate real change in my life when I am most angry. Once the pendulum begins to swing back to feelings of shame and obligation to nurture, I sink again inside myself. I shadow. I disappear.

GP: Could you explore, or explain, more of your meditations on the connections between humans and other animals? Your series on secrets written inside various animals mouths’ is incredibly compelling. The idea that an animal carries a secret, and that it could be translated into a language we could come close to understanding. I’m in love with the notion.

JV: My intent in this series is to expose the complicated intricacies of toxic and abusive relationships. How sometimes the lines blur between predator and prey. That can be a dangerous idea — that there could be a blurred line. Society always wants a perfect victim to believe but there is no such thing. Society also wants an exactingly evil predator to vilify but again, that is an unrealistic notion. Humans are flawed, imperfect — all of us. I wanted to illustrate that by way of exposing some of the secrets I’ve long held.

Each nonhuman predator in this series represents a real person from my life. These poems use the predatory traits of the animal to reveal the same of the human. In some, prey functions as predator and vice-versa. In each, we are complicated beings fraught with flaws and wounds that guide our behaviors. The undercurrent of the secret series hopes to both serve and complicate the overarching theme of prey: examining how a person becomes prey.

GP: There is so much of the body in this book — the body as your own, as another’s, as parts, as viewed. How did you feel as a human with a body as you wrote these poems? What sensations, or awareness’, did you have to inhabit, and how did it feel to put these into words?

JV: As a survivor of domestic abuse and multiple rapes, I have a skewed relationship with my body. I’ve lived in this skin my entire life, but it has not always been mine — meaning, it has repeatedly been taken, used, or harmed without my consent. I have dissociated from my own body repeatedly — the brain automatically disengaging as psychological defense. I attempt to illustrate this in my writing — ever searching for more precise and exacting ways to invoke understanding in the reader.

In the work/moment of writing, I distance myself from the violence. I cannot inhabit the memories in real-time and effectively articulate them. I have to separate myself lest I trigger a panic attack. It’s all still here — my body remembers the pressure of the thumb that left the bruise, the fingernail that took the skin, etc. Down to the finest detail, my body remembers. My job as a writer is to communicate my knowledge and experience, not torture myself.

GP: Hands appear in so many of your poems — is this meditation, this circling around a very human trait, intentional? Hands are a very human trait, I personally find them odd, and wonder how we would have evolved if our hands didn’t exist, or if they worked differently.

JV: Yes, throughout this book — and throughout my body of work — hands appear and reappear and multiply. Because of my lived experience with abuse, I have an acute awareness of (and dysfunctional relationship with) human hands. Hands wield physical power. Hands overtake. Hands grip. Hands choke. Hands bind. Hands scratch. Hands tear. Hands penetrate. Hands shove. Hands strike. Hands also build and mend and stroke and create and caress. Hands are powerful machines. Indeed, hands are the primary evolutionary factor that has rendered humans king predator.

Therefore, in a literature examining how a human can become prey, the hands are inextricable. Throughout these poems, hands are alternately conquering and conquered. They multiply, vanish, and transform. They perpetuate violence and tenderness. We are capable of incalculable things because of these powerful tools.

GP: How do you enter your writing about ‘family’ and ‘home’? We all have complex relationships to these concepts, and they have consciously and subconsciously shaped each of our existences, our individual ‘nows.’ This might be an unfair question, and one that can be interpreted and answered in many different ways. Maybe a better way to frame my own question is to ask how much of your writing about family is intentional (and how may you have prepared for this writing, over time and as you knew you wanted to write about it)? How much did it choose you?

JV: I could not omit consideration of family, home, nurture (and its absence) in the making of a person — in the making of me — while exploring the process of becoming (prey). Though this book draws no conclusions, it further investigates the impact of childhood trauma: how a survivor of such might be rendered vulnerable — or somehow predisposed — to future abuse.

As addressed in the poem “He Wants to Know Why Sometimes in the Face of Conflict…,” a child who learns that love is inexorably tethered to pain may reach adulthood with insufficient relationship skills. That child might spend their lifetime conflating love and pain, might develop a practice of over-forgiveness, might become particularly susceptible to gaslighting, might default to unhealthy ways of navigating conflict, might find respite in self-harm — an ongoing destructive cycle. It has taken decades for me to put language to these traits. So while the writing and sharing of these stories is intentional, I cannot say I prepared for it so much as simply gave myself permission.

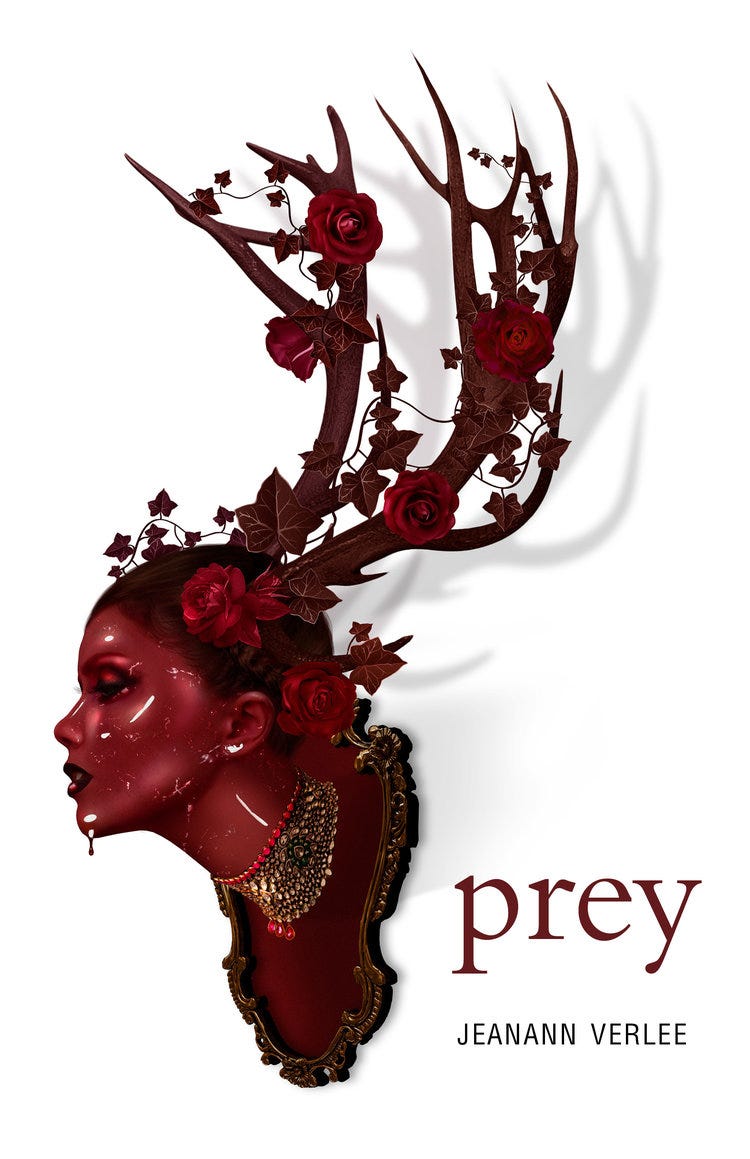

Jeanann Verlee is the author of three books: prey, finalist for the Benjamin Saltman Award (Black Lawrence, 2018); Said the Manic to the Muse (Write Bloody, 2015); and Racing Hummingbirds, silver medal winner in the Independent Publisher Awards (Write Bloody, 2010). She has been awarded a National Endowment for the Arts Poetry Fellowship, the Third Coast Poetry Prize, and the Sandy Crimmins National Prize. Her poems and essays are featured in a number of journals, including Academy of American Poets, Adroit, BuzzFeed, and Muzzle. She has served as poetry editor for Winter Tangerine Review and Union Station, among others, and as copy editor for multiple individual collections. Former director of Urbana Poetry Slam where she served as writing and performance coach, Verlee performs and facilitates workshops at schools, theatres, libraries, bookstores, and dive bars across North America. She collects tattoos, kisses Rottweilers, and believes in you. Find her at jeanannverlee.com.

Genevieve facilitates workshops with survivors of sexual assault and harassment. Her work has been published in a few places including Juked, So to Speak, Crack the Spine, Stone Canoe, BlazeVox, and The Write Room. She oscillates between NYC and the mountains, and you can find her where there are trees.

You can learn about Genevieve’s project exploring herbal birth control’s role in medieval Europe’s witch trials and in colonization of the Americas, and the resulting influences on personal and bioregional health at https://medium.com/@GenevieveJeanne

When You Are Prey: A Conversation With Jeanann Verlee & Genevieve Pfeiffer was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.