Lynn Lurie: In Great American Desert you return home. From the story “Dutch Joe,” “We settlers have pushed all the way into the pockets of Lady America… we perceive the urgency of the land’s fecundity to be ours, it is so empty and waiting.” Your first novel Cannibal, is narrated by a nameless, mostly placeless and timeless woman, who makes one reference to her origin late in the novel, “ I am telling him my father has cows, I come from a place that is as flat as this. ” After Cannibal, home becomes more evident in your novels. But you don’t write about your children, not even obliquely. It would seem you have a fidelity to them that is so fierce, so maternal that despite all the risks you take as a writer this is a subject you have walled off. Can you talk about this?

Terese Svoboda: My first child died at the age of four in an accident. There is no grief as wild as this. He is buried in all my novels, and in three of the stories in Great American Desert. But this collection really concerns a more primal coming-to-grips: my own father’s long dying.

TS: This new novel of yours, Museum of Stones, is written in oblique prose touched with the concision of poetry, and marked by the fragmentary nature of memory that unite all three of your novels. Corner of the Dead evokes a young American woman encountering the Shining Light in Peru and the execution of incomprehensible evil, and understanding her place in it. Sections depicting the villagers in extremis are interspersed with her life as a volunteer. Quick Kills is the story of a young photographer who is lured into the art by a pedophile, unprotected by her family. A strange and inconsolable son is at the heart of Museum of Stones, a character who overwhelms the mother with his inchoate demands, yet the book echoes not only the form but some of the subject matter of the previous two. Peru is where the mother and son volunteer, and the difficult family continues its demands on the narrator. Many authors re-articulate their concerns from book to book, hoping to get them right or to set them right. What is your intent?

LL: Yes, all three books overlap and share a number of similarities. If I were the sort of writer who plotted and planned I might have thought to write a trilogy. Each novel provides a new context for examining, what are loosely, three significant events in my life. Understanding how they have marked me remains an unfinished task. This also defines the process of writing: I am never done. In each novel I take new risks, not only with the subject matter but also with the form. So while all three dance around the same issues, with each subsequent book, I have tried to push further. I would love to be done and on to something else, but despite my efforts I keep circling back.

Tin God gives a sense of vastness of the prairie and of what the land has witnessed over time and in Bohemian Girl we are also west in the 19th century. The girl is chattel the father bargains with to pay off a debt. You have stories of a father of a gun, a pick up truck, of men. Have you struggled with how your work is received by those who might see themselves in the work?

TS: When All Aberration, my first book of poetry, was published, my mother complained that I made her sound fat, when really there were a number of poems that portrayed her as unloving. That’s when I realized “those who might see themselves in the work” would see what they wanted. I am, however, relieved that my father died last month.

What is it about the negative space between your paragraphs that generates so much power in your work? I’ve often thought of your work as a hybrid prose poetry, but this last book is the one that most resembles that form in that it moves from section to section with a mysterious unity, like a much shorter Underworld. Would you appreciate such a label or do you prefer to be thought of solely as a novelist? And why.

LL: I don’t think I have written novels or poems. My work doesn’t fit comfortably in either box. It may be because I am revising the same questions the hybrid form makes most sense. It allows me more opportunities to find the connections. My sense of the novel is that it has a distinct beginning, middle and end and is plot driven. Plot and a formal structure often hamper me, which is why I use both minimally. I prefer to let the stories unfold in a non-linear fashion, the momentum determined by memory and how images come to me. I don’t think my stories come to a full stop, but rather end with motion more akin to yielding. I prefer to hold back from excess description and context, which often detract from the emotional content and impede the reader’s imagination. So hybrid might be the most accurate moniker.

As regards the spacing, there is a consistency as to when it occurs in all three works. The white space is employed when author and reader are in need of air. It provides reprieve. Museum of Stones relies most heavily on spacing: it was the most difficult story to tell. Its narrator is the most fragile of the three and the vulnerability of the son, at times, pulses as if it is its own character. I needed to work up to Museum of Stones and the prior two books gave me that courage. The white space also allows the reader to spend more time with what she has just read.

I ask a lot of the reader with these spaces and am grateful for those who find something in the layering. I was trained as a black and white photographer and I still think in gradations of grey, the way shadow can ultimately create an image even when none is clearly visible.

LL: Black Glasses like Clark Kent is a memoir of your uncle. How did you manage the weight of the material and the sensitivity of the subject? The effort here I would imagine is different than in a novel as you are working with facts.

TS: My uncle told me to take the tapes he dictated and do what I wanted with them. In following his story, I had to explore issues of race, social justice, white supremacy, and the debasement of women to understand what made him operate as an 18-year-old MP in post-war Japan. Early on I decided that the power of the material was in the facts. The structure of the book is related to the discovery of the facts: I reveal them as I find them. Most of the stories in Great American Desert are fact-based and researched, except the mythological and sci-fi. Truth is always so strange.

TS: The mother in Museum of Stones suffers from altitude sickness and must abandon her son in order to save her life in the midst of political chaos. His escape and their reunion is one of the most gripping parts of the book, where all the vectors of his personal terrors rise up. Earlier, the mother nearly comes apart while caring for him. What are the challenges of a writer when describing these kinds of mental stress?

LL: You are the perfect reader.The writing of mental stress requires an unforgiving and unflattering investigation into motives, a reckoning of inadequacies, an exorcism of weaknesses. My writing often borders on violating confidences. Perhaps it crosses the line and when it does it causes pain, which is never my intent. I spend a lot of time rewriting just to minimize this. It is hurtful to close my eyes and feel what I, at other times in my life, worked so hard to forget. When it works I am rewarded, when it fails, I am despondent.

LL: In Great American Desert you return home to the west with a vengeance. There is a love for this land, for these people, for the trauma of living here. The collection underscores you are a writer of The United States, the frontier. Was the need to put these stories together related to events of late that are undermining our America?

TS: Since the stories were written over a period of 25 years, I can’t say that they were written in response to recent events, but the thread I found to hold them together, climate concern, is timely. I have, however, written about the environment before. My second novel, A Drink Called Paradise, is about the Pacific peoples who still suffer so much from postwar bomb tests. Radiation is almost as timeless as the degradation of the earth, at least from the human perspective.

The narrator of Museum of Stones returns to Peru to work with poor and illiterate patients. How does the foreignness of the location illuminate what is essentially an intimate story of the heart, mother and son?

LL: The foreignness is a screen and when it is gives way, she is whittled down to her rawest form. It allows her to feel her own circumstances from a slight distance and that makes her momentarily less afraid to assess them. She learns the most about herself if she can feel it first through someone else’s viewfinder.

Peru bleeds through all three novels. It was in that part of the world, when I was young, that I lived with people who were stripped to the barest of living conditions, and who, with so little, made art, raised children and somehow remained gentle and generous. Acts of kindness are what sustained them when floods took their huts and provisions and when the military swooped in and took the rest. I wanted desperately to emulate the way they managed hardship, to be useful and to be humane. This meant a lot of failure on my part.

Something happens in the story “Africa” that you carry forward in the remaining stories in Great American Desert. I wonder if the ordering of the stories was to reflect that the narrator is beginning to become more present? “Africa” is still told in the third person, but then there is another shift to a series of stories with a first person narrating. We now feel we are in the present tense, with the timelessness of some of the other stories, particularly the first in the collection, gone. We have been brought inside, closer. “Mugsy” is breathtaking for this reason, as are the stories after Mugsy, seemingly culminating in “Hot Rain,” which is wrenching, desperate and exquisite. Will you continue with this in your next work? Why are these stories at the end of the collection?

TS: “Something bad happened” is easier to handle than “something bad happened to me.” There’s also a progression from the young protagonists in “Camp Clovis” to the awkward romance between the sister-in-law and the husband in “Dirty Thirties” to the elderly in a story like “Seconds.” The second-to-last story in the collection is a retelling of a fairy tale, and the very last is sci-fi, both otherworldly, stories told late, perhaps after death. Is that a movement toward self-reckoning? These days I’m using a ten-foot-pole to write about race and sex, cracking off little bits of me for examination. I don’t always want to go where “Hot Rain” came from.

The extended family in Museum of Stones work at cross-purposes to the narrator, depleting her maternal energies, as well as refusing to acknowledge her own childhood struggles. The way you have interspersed and layered their ripostes gives us both texture and backstory. Did you use some kind of chart to position the sections or was this intuitive?

LL: No chart. Raising children it is impossible to not remember growing up. Things long buried or never examined resurfaced. Images would come to me unbidden and linger and then branch into other memories without obvious connection. This, too, is how I write. I need to find the connective tissue. The narrator’s responses to her son are a function of the parenting she received and the best way to illuminate this was by dispersing, in zigzagging bits, past information. I couldn’t have done it any other way because the story isn’t about the narrator but about the-narrator-and-her son. They are not severable.

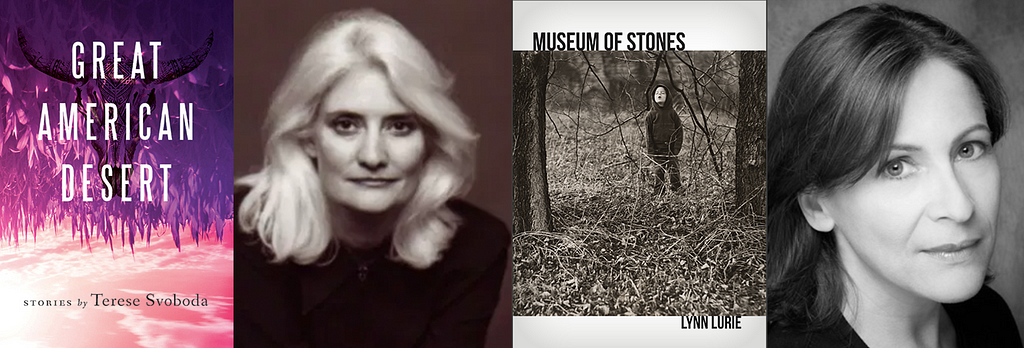

A Guggenheim fellow, Terese Svoboda is the author of seven books of fiction, seven books of poetry, a prize-winning memoir, a book of translation from the Nuer, and a biography of the radical poet Lola Ridge. The Bloomsbury Review writes that “Terese Svoboda is one of those writers you would be tempted to read regardless of the setting or the period or the plot or even the genre.” Her short story collection, Great American Desert, was just launched by Ohio State University Press.

Lynn Lurie is the author of two previous novels, Corner of the Dead (2008), winner of the Juniper Prize for Fiction, and Quick Kills (2014). An attorney with an MA in international affairs and an MFA in writing, she is a graduate of Barnard College and Columbia University. She served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Ecuador and currently teaches creative writing and literature to incarcerated men. She has served as a translator and administrator on medical trips to South America providing surgery free of charge to children, and has mentored at Girls Write Now in New York City. Her new book, Museum of Stones, was just launched by Etruscan Press.

The Truth Is Always So Strange: A Conversation With Lynn Lurie & Terese Svoboda was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.