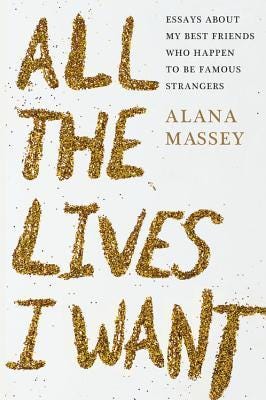

Like many readers, I originally encountered Alana Massey through her freelance nonfiction writing, scrolling through her essays in online publications like The New Inquiry and LitHub, among many others. A lot of her works could be considered “personal essays:” critics declare the death of this genre every other week, but great personal essays somehow keep being written.

In her debut essay collection, All the Lives I Want: Essays About My Best Friends Who Happen to be Famous Strangers (Grand Central, 2017), Massey discusses various women celebrities of the recent past, from the manufactured rivalry of Nicki Minaj and Lil’ Kim to the intertwined fame of Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. While the essays are primarily works of cultural criticism, Massey infuses them with a kind of interiority that lends compassion to the act of examining the lives of famous women, an act we would typically see only in the harsh lens of tabloids. Through this personal gaze, she also highlights how no cultural criticism can be objective: as a thin white woman, she occupies a particular axis of privilege in terms of whose thoughts about pop culture will be published in the first place.

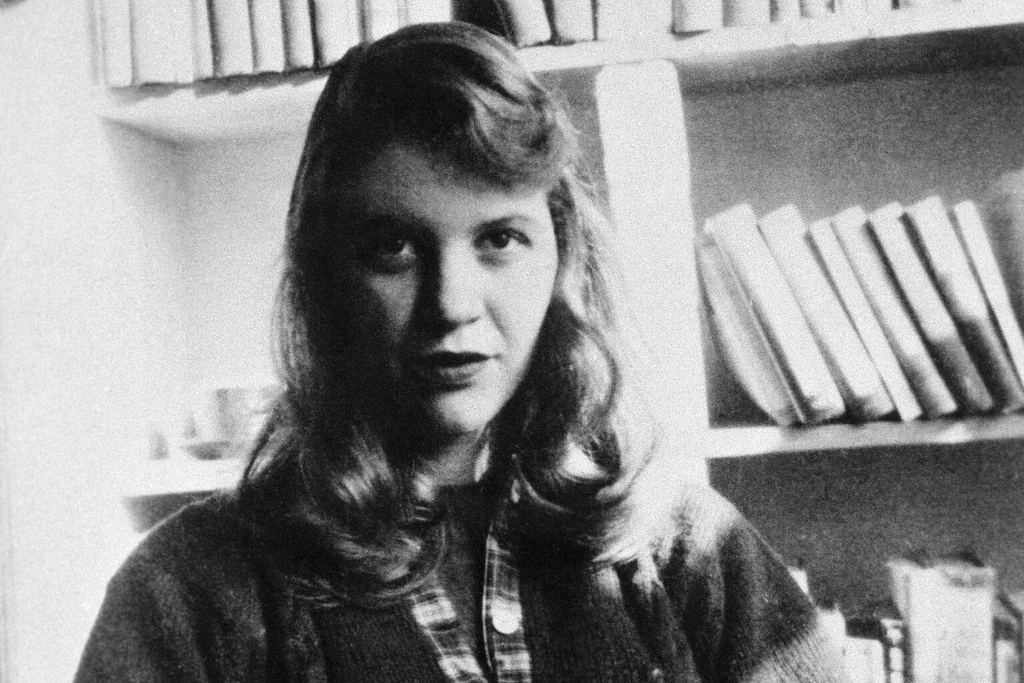

The collection’s titular essay is somewhat of an outlier in that it centers a not-so-recent celebrity. In “All the Lives I Want: Recovering Sylvia Plath,” Massey unpacks some of the gendered reasons why the establishment refuses to take Plath seriously. She cites one particularly heartbreaking line from the New York Review of Books that calls her a “sensation among bulimic female undergraduates.” Even if that were true, why should a writer’s appeal to ostensible “sad girls” make her work any less legitimate in the canon?

In a warm yet still analytical passage, Massey discusses the way young girls are often dismissed for demonstrations of passion like “wearing T-shirts of boy bands or one half of a best-friend-necklace pairing,” when the openness of displaying one’s devotion to anything or anyone could be considered an act of bravery. She then explores the way girls have formed certain corners of the internet — from Tumblr pages to Etsy shops—devoted to a feminine aesthetic that often invokes Sylvia Plath’s words or includes images of her.

Massey describes the experience of finding images of tattoos within the “Sylvia Plath” tag on Tumblr:

I find myself returning over and over to an image of skin bearing the haunting finale of The Bell Jar: ‘I am, I am, I am.’ […] Sometimes it is accompanied by its preceding line, ‘I took a deep breath and listened to the old brag of my heart.’ I struggle to think of any line of thinking more linked to being a socialized female than to consider the declaration of simply existing to feel like a form of bragging. But that, of course, is the plight of the feeling girl: to be told again and again that her very existence is something not worth declaring.

This “declaration of simply existing” as somehow presumptuous also extends to the documentation of one’s own interiority. Later in the essay, Massey expands her discussion and considers how Plath’s introspective writings might be compared to “a young woman who takes endless selfies and posts them with vicious captions calling herself fat and ugly.”

At first, as a reader, I recoil from this comparison. How dare she belittle Plath in such a way? But then, Massey continues:

She is at once her own documentarian and the reflexive voice that says she is unworthy of documentation. She sends her image into the world to be seen, discussed, and devoured, proclaiming that the ordinariness or ugliness of her existence does not remove her right to have it.

In this way, Massey repeatedly constructs clever turns in her prose to open up new ways of treating the world with a gaze that is at once shrewd and tender. The essay about “recovering” Sylvia Plath somehow colors all of the other discussions—from Anna Nicole Smith to Princess Diana—with the self-aware notion that to apply a respectful, thoughtful gaze to famous women can be a way of recovering them from the exterior narratives that seek to define them.

In an interview with The Rumpus, Alana Massey was asked about personal essays and memoirs as a “maligned form of writing.” She replied:

I think the disdain for the memoir genre is distinctly gendered; we believe that men who write about themselves are writing about the universal because we believe that men are the default human identity, while women who write about themselves are gazing inward and being selfish […] what I was trying to do here was cultural criticism and I put myself in the book because I bristle at the idea of objective criticism in this context.

The idea that the disdain for memoir is rooted in misogyny is nothing new, but the particular mode of addressing it in All the Lives I Want is worth dwelling on. It is a practice in blending genres as well as interiorities. Massey repeatedly asserts the existence of women’s own complex stories, no matter how much the dominant cultural narratives might sculpt them into entities instead of people.

The moments of personal writing in these essays therefore do not belittle the intellectual rigor of her criticism. They are instead a way of formally weaving in that refrain, I am, I am, I am, where the voice and stories of the writer are necessarily inextricable from those of her subjects.

Alana Massey and the Cultures of Girlhood was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.