Arturo Desimone’s series on Latin American poetry, blogging for Anomaly

In Conversation with Lucina Schell: Importing Miguel Bustos’s VISION OF THE CHILDREN OF EVIL to a New Tongue and New Shore

“I believe poetry to be of divine origin. That I believe absolutely. From the moment it has a secret origin and a hidden origin…Despite that I believe it has a secret, occult, divine personal well-spring in every poet, that does not dissuade me from a life of political militancy. Of course I do not write from divine source…it is better to concede that a militant career comes to take us, than to attempt escape.” — Bustos, in an interview with Clarín newspaper in 1971

Anomaly sat down for conversation with Chicago-based translator Lucina Schell about her translations of Miguel-Ángel Bustos, a major Argentinean poet, journalist, surrealist and mystic. His first book, Corazón de Piel Afuera (Heart of Inside-Out Skin) was praised by Juan Gelman as “without precedent in Argentine poetry, of a powerful and mature, unexpected tender lyrical flight.” Later came Vision of the Children of Evil (Visión de los Hijos del Mal) and Fragmentos Fantásticos (Fantastic Fragments), collections translated into English for the first time by Schell, forthcoming this fall from co-im-press. Censored for years after the dawn of Argentine democracy, Bustos lives upon lips of many Argentine 21st century poets seeking to counter today’s literary mainstream.

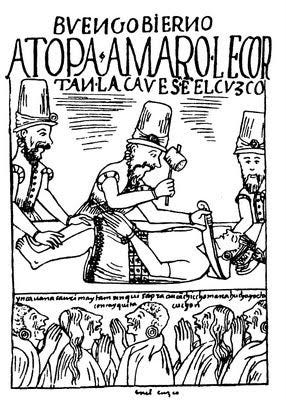

Bustos’ illustrated manuscripts map the continent’s atrocious history, recalling visual chronicles of16th century Peruvian artist Guamán Poma de Ayala and Guevara’s famed motorcycle diaries. Wanderings also brought him through Buenos Aires’ labyrinthine Borda psychiatric hospital— where he encountered poet Jacobo Fijman, a kindred spirit. The state terror detained Bustos in 1976 for “subversion.”

The poet’s remains were forensically identified in 2014. His son, the poet Emiliano Bustos, sought to preserve Miguel Ángel’s legacy against continuing censorship during the post-dictatorial “Amnesty” period, and met our interviewee during the years she inhabited Argentina. Schell deeply invested herself in Argentina, as our interview will prove. She resurrects poètes maudits, poets of the damned, internationally, translating from Spanish or French. The translator and founding-editor of Reading In Translation (a review of literature in translation) has worked in international rights for University of Chicago Press and her work on Bustos appeared in Drunken Boat, Jacket2, Ezra Translation Journal and Bitter Oleander…and right here.

Arturo Desimone: Your fascination with the country of Bustos remains a mystery unexplained by your biography. A review you wrote of translator Lisa Bradford’s work on Juan Gelman is meticulous, showing very specific knowledge of Buenos Aires dialect (in Lunfardo, a coded language made by immigrants and the underworld, they sometimes substitute the n for an r in Spanish words, for example, as you point out). What brought you to Argentina? Why bring Anglos into conversation with this gut-wrenching country? What has been your experience of Argentineans and how do you put up their way of pronouncing?

Lucina Schell: I studied in Córdoba, Argentina, in 2010, which was where I came across Miguel Ángel Bustos’s Visión de los hijos del mal. Poesía completa, edited and published by his son Emiliano Bustos with Editorial Argonauta in 2008. That was the first time his poetry had been in print since his disappearance in 1976, and the first time the unpublished poetry had ever been collected. As a result of studying in Argentina, my Spanish, which I’ve studied as a second language for most of my life, became “argentinizado.” I’m most comfortable speaking in Spanish with Argentinians, when I can use the voseo (Ed. a grammatical form used in the Spanish of Argentina — see endnote) and particular vocabulary.

Argentina and the US have a parallel, intertwined history and we have much to learn from one another. Argentina, like the United States, waged a genocide against its indigenous population in the 19th Century, and was largely settled by immigrants. In the 20th Century, the US has a dark history of involvement in Latin America, including in the military dictatorship that took Bustos’s life. And, bringing us to today, North American neoliberalism continues to have a malign influence in Argentina and Latin America more broadly.

To be more specific, I feel strongly that the two books I have translated by Bustos, Fantastical Fragments and Vision of the Children of Evil, written for a pan-American audience, are essential reading for Americans in the U.S. The vision Bustos celebrates of Argentina — and America — as a syncretic, diverse amalgam of cultures both indigenous and violently imported, ran counter to the military junta’s enforced monolithic European, Christian Argentine identity, which defined Argentina against its more darkly coloured neighbours and sought to erase the genocide of the country’s indigenous population, marginalization of its African-descended population, and the legacy of persecution its European Jewish population had sought to escape. And that vision continues to be a strong rebuke of the vision of American identity advanced by President Trump and the ascendant white supremacy in the United States.

AD: The U.S. policy that backed the Argentinean regime that killed Bustos evidenced very explicit, direct involvement. To this day, many Argentineans resent the USA because of the junta and subsequent economic policies, most recently visible when Obama came to visit in 2016, and a protest of many thousands (coinciding with Día de la Memoria on March 24th) raged in Buenos Aires on and around the May Plaza. Does that historical connection between the USA and Andean regimes bring you closer to Bustos and the Argentine poets of his era? Or does it alienate the translator (as well as readers)?

LS: I never experienced resentment from Argentineans directed at me personally while living there. Argentineans distinguish the citizens from their government’s policies. But this shared and painful history brings me closer to Bustos. I feel that responsibility to amplify in English this voice that was silenced. Not only as an American — but foremost as someone who connects with his work in a special way.

I remember my very visceral emotional response when reading of Obama’s visit to Argentina — although I’m not Argentinian, I was personally offended. On one level, I had lived in Argentina and experienced the reverberations of this violence up into the present day — there are still disappeared whose fates are unknown, whose remains have never been found, and the Abuelas de la Plaza de Mayo are still finding the identities of (now adult) children that were stolen by the regime. As an American in Argentina, every time I read about the process of justice in the press, there was the shame. I feel a very close relationship with Bustos. That state violence my government participated in, took someone from me, and that angers me — it took someone from all of us who care about great literature.

Barack Obama’s visit was even more personal after working on Bustos’s poetry for six years. The visit was a missed opportunity, as my president stopped short of apologizing for the US role in the dictatorship. It coincided with the legitimization of the newly elected Macri administration, which has from the beginning obstructed the process of memory and justice for victims of the dictatorship, even questioning whether the estimated 30,000 disappeared is not an inflated number to take advantage of government assistance. I saw my president — one I generally admired — tossing flowers into the river beside Macri. Such political charades make one cynical. (Note: this is the same river where many of the state’s hostages were once dropped from airplanes and helicopters as a form of execution. -Ed/Artu)

I hope my translations of Bustos inspire my fellow citizens to take interest in our country’s role in Argentina’s violent history, to feel emotionally closer, and responsible toward, another part of the world.

AD: Your review of Lisa Bradford’s translation of Cólera Buey, Oxen Rage ends with a radical and confronting statement to the American poetry academy: “In the face of American poetry’s increasingly alarming insularity, Gelman’s revolutionary book demonstrates the rich ‘con/versation’ that can only come from engagement with other languages and traditions” and a bit later you are at it again decrying “limitations we impose on international writing.” How do you see this insularity, the resistance to foreign influences, in the current political-liberal and literary landscape?

LS: It is an enormous privilege to share a list at co-im-press with the immensely talented Lisa Rose Bradford, and it has been my pleasure to review her brilliant translations of Juan Gelman over the years. Argentine Spanish is unique, and I learned a lot from Lisa’s translations. To place Bustos beside Gelman, his contemporary, who was fortunate to live a full life and become one of Argentina’s most well-known and acclaimed poets in translation, feels like a restoration. Gelman blurbed and reviewed Bustos’s books during his lifetime, and even wrote poems about him before and after his disappearance. They were very much in conversation.

Earlier generations of American poets, like Ezra Pound, Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and W.S. Merwin, engaged in translation more often as a necessary part of creative work, and that enriched the techniques and vocabulary available to us. The hegemony of English has enabled contemporary American poets to pretty much ignore what’s going on in poetry in the outside world— an unfortunate “luxury” that no poet writing in any other language can afford, and that ultimately impoverishes literature.

The best translators of poetry, certainly the best American poets to my mind, are poets engaged in translation — poets like Mark Statman, Forrest Gander, Daniel Borzutzky, Lisa Rose Bradford, Katherine Hedeen, Jesse Lee Kercheval… there are many others.

Unfortunately many American poets coming from the writing workshops have a limited notion of the place of poetry in society. They are largely talking to themselves. But poets like those I mentioned are actively working against this in their teaching and publications; the role of translation is evident in their own poetry. Translation has always been a source of inspiration to me in my own writing.

AD: If I may dwell a little more on the negative aspect: does this U.S./Anglo insularity also delimit how even the best translators’ work is showcased? An example I’m thinking of: after Trump’s rise, literary mags devoted to “world literature” started expressly publishing translations of specifically those nationalities on Trump’s immigration ban blacklists like Somalia. Is this reaction from the lit bubble futile, a politically correct, or a useful universalizing gesture?

What are the expectations imposed by the Western major literary journals on poets and writers from Latin America, and can such imposed expectations be authentic and well-intended? How do the insularity and imposed expectations manifest in the indie press scene?

LS: Now you are getting at the political role of translation. I think the commitment from mainly indie presses in reaction to Trump’s nationalistic policies to publish work from the countries affected by the travel ban is largely positive. It’s wonderful that work from Somalia is being published, but publishers should have been seeking out this work a long time ago. Now that Somalia figures in the travel ban of an unpopular president, we are playing catch-up, trying to figure out who the important Somalian writers are, what Somalia’s all about, to fill in the gaps that led to myopic policies like this in the first place.

Making more international literature available to American readers is always a good thing. The problem comes when its value is tied to a momentary trend. The marketing angle always has to be considered when it comes to translation: most American publishers consider it risky. We like our translations to be “representative” of a culture, but that can be based on very narrow perceptions of that culture.

When it comes to Latin American writers, the popular narrative and marketing angle in the US is…dictatorship. Even literature that is not overtly political or about (post)dictatorship can be marketed this way. It’s so ironic because the United States played a role in these dictatorships, and now Americans read political work about them, almost a sort of atonement or self-flagellation, without really confronting what our country did in Latin America.

Bustos was disappeared during the last Argentine dictatorship. That is a tragedy. We lost one of our great writers at the height of his creative powers. But I want to resist marketing him that way. Bustos wrote very little overtly political poetry. At the end of the day, I want Bustos’s poetry to be judged and valued on its literary merit — I think it should be read for its beauty.

I can’t complain

if it was a body that climbed then a body is in the heavens among the gold and silver winds the rain of frozen stones.

Along with the Veins and Sap grow pastures of fire. To

see a human soul that will not open fragrant and resonant sees nothing.

— Miguel Bustos, trans. Lucina Schell

AD: Viewed by a Latin American visitor — this one, in any case — the USA looks like a consumer-society in denial of mortality, and where the mentality is largely pragmatist, problem-solving, comfort-seeking. Texan literary critic Anis Shivani, interviewed by the Drunken Boat and elsewhere, decries a “culture of therapy and consolation” and denial of mortality as part of the problem underlying (North) American lit culture today.

Can Bustos, a poet who wrote of the violence of death, and who talks about the spirit / soul / heart, have any resonance in a different cultural context that we inhabit as 21st century people? What can Bustos tell your audience, about Argentina and about your society, under Trump’s White House but also in years to come in the afterglow? How can a spiritual poet with so many religious references be read in today’s culture that sees poetry perhaps at best as some kind of placebo or escape valve, in a scientific capitalist society?

LS: I disagree that poetry functions as an escape valve. If anything, I think it’s the proliferation of dystopian and superhero films that serve that function, which I think is a very bad sign of where we’re heading and how we conceptualize the possibility of a future. Poetry can offer comfort in a violent and troubling world, and I think that’s the role it plays for the general reader — she turns to poetry in a time of crisis. I think poetry has the capacity to convey painful truths in a “palatable” way, one that can infiltrate mainstream society under the veneer of the aesthetic. Some fantastic political poetry is being written today — Tracy K. Smith, Claudia Rankine, Jamila Woods, Danez Smith, Layli Long Soldier come to mind — that I think has the power to speak to a universal audience.

To go back to Bustos, he is a deeply spiritual poet, and I think that has always made him difficult to place, both in his own time, and now. Bustos’s work is part of the classical epic tradition of the spiritual journey. The role of the poet in his work is much broader than we usually grant it today — that of a prophet.

62. Who will take off my life like a sweat-and-blood-soaked shirt?

Curse me, nail me to the cross, to the cross of the love

that sprouts from my groin like a weed of Hell.

Here my beasts, I want to possess a tiger, to give

birth to the visionary god.

— Miguel Bustos, trans. Lucina Schell

I don’t know if we’re afraid of death in the West so much as obsessed by it. The end point of capitalism is death, we are hurtling toward our own destruction, desperately looking for ways of distracting ourselves, whether through escapist fiction and virtual reality, or simply amassing more things to fill our lives. I think Bustos speaks urgently to North American readers. His critique of capitalism in poems like “A Horizontal Job” is both humorous and deadly serious. Bustos was not afraid of death — he had seen it already, he had been there and back. At one time, he chose death for himself, but survived. We need to remember that there are worse things than death.

Bustos is also a symbolist poet, so it’s important to remember that when he employs conceptual abstractions like heart, heaven, moon, water, metal, he is using them as metonyms for all the associations they bring up across literature — as well as, in a postcolonial and capitalist context, how that religious language was used to subjugate, and the colonial and neo-colonial project of resource extraction.

The project of the Trump administration, like the Argentine military junta of 1976, is to minimize the multiplicity of American identity, to draw up borders around it that enclose only white and Christian inhabitants, and Bustos’s poetry vociferously defends against this narrowing of Argentine and American identity.

AD: In preface to an interview you took with the translator of Jordanian Bedouin poet Tayseer al-Sboul, you find a parallel between the Bedouin poetry and that of Bustos: “While reading the poems in Desert Sorrows, I recognized the painful lucidity and searing compassion that aligns Tayseer with other writers who plumbed the depths of the human condition, like the Argentine poet I’ve spent the past few years translating, Miguel Ángel Bustos.” How do Bustos and the Bedouin poet resemble one another, trans-migrating or cross-pollinating paths? Because of wanderings? Intensity of experience /vision?

LS: Their poetry is very different, but I think they are kindred souls. Bustos has a kinship with a long lineage of poets who suffered from depression and a crushing level of empathy with the world, like the Jordanian poet Tayseer al-Sboul. Bustos also suffered from epilepsy, through which he experienced visions that inform his work. The book Fragmentos fantásticos was born out of a nervous breakdown that led Bustos to be briefly institutionalized. It is a literary descent into hell in the tradition of the poètes maudits, and the epigraphs to the various sections point to those poets with whom Bustos converses: Baudelaire, Nerval, Artaud, Poe — and though he isn’t directly named, especially Arthur Rimbaud. Rimbaud called for the creation of a universal, synesthetic language, and Bustos takes up that project in resistance to the violence of colonialism, the erasure of indigenous language, culture, and history.

Bustos was certainly a maldito — a cursed poet — and in Spanish this lineage comes down through Vallejo, another important influence. In addition, Bustos was influenced by Eastern poets and the foundational Hindu, Sufi, and Buddhist religious texts, which becomes more explicit in later poetry. So, his work is deeply intertextual, engaging with seemingly disparate cultures and mythologies. The source of Bustos’s political activism, as it was for Tayseer, is his deep empathy with the human condition.

SONG OF THE BLESSED

Lord Lord why have you forsaken me

if I was inhumane

but prayed every Sunday.

I tried to be an altar

seven weekly communions for me

your blood a singular gold.

Now I give myself twenty-four bell peals

and sleep like a clump of earth.

When I die

beneath the inhumane song of my

brothers

I’ll be a relic urine smell.

I’ll remain in my bones for all

eternity. Amen.

— Miguel-Ángel Bustos, trans. Lucina Schell

AD: In a preface to a relatively recent collected poems published in 2008, Vision of the Children of Evil: Complete Poems, his son Emiliano Bustos speaks of how ever since his father joined the 30,000 disappeared and until that date, the ideas and art of his father endured a forced exile. In your note in Drunken Boat, you also mentioned the enduring years of censorship. Censorship, and the stigma affecting all exiles, continued long after the end of dictatorship. When you first took it upon yourself to translate this poet, did you ever encounter the censors guarding his work long after the end of the dictatorship? How did the censorship post-Junta manifest then in its vestiges in democratized Argentina? Usually it seems there is an immense market-interest for censored third-world writers (look at Rushdie, or recent cases like El Salvadoran poet novelist Jorge Galán). Why, then, was the dust they threw on Bustos so resilient? Where is PEN?

LS: I encountered Bustos’s poetry toward the end of my time in Argentina, and I unfortunately haven’t been back since, so I can’t really speak to the current reception of Bustos in Argentina. Emiliano Bustos, his son who republished his poetry and prose, is also a well-known poet and public figure, and has made a tremendous effort against the erasure of his father’s work and place in the Argentine literary canon. There does seem to be a renewed recognition of Bustos’s importance on a national level, and a reversal of the previous censorship. I should note that my translation, and the recent French translation of selected poems by Stéphane Chaumet, were supported by the Programa SUR grant of the Argentine Ministry of Culture. The publicity in Argentina surrounding the publication of his collected poetry in 2008 speaks of the restoration of his place — Pagina/12 called it the “editorial event of the year” — but I think that remains a work in progress that hopefully my translations will contribute to. I am very curious what the reception of these translations will be in Argentina.

Bustos made news again in 2014 when his remains were identified by forensic anthropologists — now we know he was executed by firing squad. Still, the media coverage tends to be dominated by his status as victim of the dictatorship, and if anything, refers to his work as a journalist, which is more overtly political than his poetry, rather than as one of the most significant Argentine poets of the 20th century. So, again, I really want to resist this marketing, that his work is important as a refutation of political violence and censorship. It is, but first and foremost, it’s beautiful, complex, and vital poetry.

AD: When you translate Bustos, do you use a “model” of sorts among English-language poets who might resemble an Anglo “counterpart” to Bustos in tone and style?

LS: I wish I knew of an Anglo “counterpart” to Bustos. I’ll be very curious to see the critical response to these books here in the United States and who he is compared to in Anglophone poetry.So, to be honest, I haven’t had an Anglo model, rather I’ve studied extensively translations of the French poets I mentioned, as well as Vallejo, Golden Age Spanish poets, especially Góngora, and the texts of the Spanish conquistadors. The French maudit poets in particular I see as Bustos’s most important influences, at least in these two books, so I’ve studied translations of all of those poets to make sure that those allusions and resonances are apparent to English readers. For example, although the poem “Arreglo para cuerdas y vocales” could be translated — very naturally — as “Arrangement for Strings and Vocals,” I know it’s “Arrangement for Strings and Vowels,” because it alludes to Rimbaud’s “Voyelles.” In any case, the reader picks up the double-entendre easily.

I think my publisher Steve Halle sees Bustos as fitting into a contemporary neo-gothic movement that is transnational, and has a following among readers in the United States, although I’m not very familiar with the North American poets writing in this vein. Franz Wright was probably a maudit.

AD: Quite often a translator needs to be from an English-speaking setting, in order to make the language sound natural or relatable to the everyday-uses and understandings of the locals who do not read the source language (this challenge and criticism was presented to me, for example, when I showed my earlier translations to seasoned and accomplished translators from England who doubted that I could translate into English, since I am not immersed in a conventional English-speaking setting). How is this with Bustos and American English of your immediate surroundings?

LS: I think Bustos translates naturally into American English because I think this is a very (pan) American text. I really feel that these books are intended for an audience beyond Argentina, that they speak to Americans throughout the American continents. I’m happy that they will now reach Anglophone American readers, and I would love to see them translated into Portuguese and French in the future.

The places where British and American English really diverge, I think, are in the more informal register — the colloquial vocabulary is just totally different. So those poems that are more colloquial and playful, like the series from Fantastical Fragments published in Tupelo Quarterly, are where my choices in terms of American English become more prominent. For example, the poem “Voice and Back,” one of the most difficult to translate in the whole collection, plays on colloquial expressions like “bad blood” and sangre natural, which I’ve translated as “common blood” because the Spanish suggests an illegitimate offspring and has resonance within a colonial class system, but “common” in English also highlights the poet’s yearning to share with his beloved. Bustos also plays throughout with different associations with lomo, a very colloquial word for the back. I went back and forth with (his son )Emiliano on how to translate this, and he said he thought the poem was playing on echarle el lomo, so I inserted that, instead of “through your back,” I have, “with your back into it, it’s savage what you can / say.” By the end of the poem, the subject has turned her back on the poet.

AD: Because Spanish seems to still maintain many uses that are from the culture and era of feudal societies, and because the Spanish tongue has changed relatively little since the time of Poema Del Mío Cid if we compare the evolution of Spanish to the steps taken by French or English into modernity, is there any conflict that presents itself? Is there an inevitable “baroqueness,” a datedness or strangeness of Spanish that you find worth preserving, rather than modernizing or sprucing up, when you translate into English? How are translators to manage the challenge, the dilemma of preserving inevitable dissonances that arise due to culture and the different evolutions/trajectories of languages?

LS: Something I absorbed early on from one of my translation mentors, Mark Statman, is that each writer (or those worth reading or translating anyway) writes in his or her own language, which may look like a familiar language — Spanish, English — but which is unique to that writer. I’ve spent years on this project getting into the uniqueness of Bustos’s language. The other thing that I think translators develop over time is a sensitivity to different registers of language, an awareness of what the standards are in the source language, and what is style on the part of the writer — that has to be preserved.

One of the challenges of Bustos is that he writes in so many different forms and registers — in these two books he writes in aphoristic fragments, prose poems (in the tradition of Baudelaire), linguistically playful and experimental lineated verse, which sometimes borrows from Brazilian concrete poetry, and longer prose chapters of a few pages or so, and he writes across a spectrum of formality. Some of the poems he writes in the voice of the conquistadors, and so my translation had to preserve that somewhat archaic and very formal diction. I looked at how the chronicles of Cortés and Bartolomé de las Casas have been translated into English, and the literature of those “first encounters” between cultures that don’t understand one another, where the writer lacks the vocabulary for the things he is seeing. In Vision of the Children of Evil, Bustos writes this amazing poem “Epistle of Saint Paul to the Mayas, Incas, and Aztecs.”

It’s a bruising critique of religious hypocrisy, the use of Catholicism as a tool of conquest. And he writes it in a Spanish voice — he uses vosotros. How do you translate that? How do you convey to an English reader that the speaker is using a form of address only used in Spain, and in addition, the informal, implying a kind of familiarity with the subjects he’s addressing, almost a fatherly looking down on them? I couldn’t find a way — I mean, I translated it as “you”. But, at a minimum, it has to sound like a Spanish conquistador, with biblical tones, and I had to inhabit that perspective.

I think Spanish can be very modern — certainly Bustos pushes Spanish into very experimental and modern territory. In the more experimental poems, Bustos’s language is much less formal, and so it was important to me to strip those down, to make sure I was choosing fairly ordinary words in English. On the other hand, many of Bustos’s poems, and especially the prose poems, make extensive use of inverted syntax, which can be quite gnarly to untangle for a translator. This is a characteristic of Bustos’s poetry, but also has its origins in the hiperbaton common in Golden Age Spanish poetry. Again, that had to be preserved, yet at the same time, the English reader has to be able to follow the sense of the sentence, to figure out what the subject is.

For example, from Fragmentos fantásticos: “una vibrante rama de acero estará en las venas el amor que / hoy tengo un grito brutal olvidado muerto,” which I have translated as, “the love I have in my veins today will be a throbbing / branch of steel a brutal forgotten dead cry.” You’ll notice that I have reordered the sentence, to make it easier to follow, but also to preserve the ambiguity engendered by the lack of punctuation between the clauses, such that they can be read backwards and forwards with different meanings. This is another particularity of Bustos, he does this all the time.

A more straightforward example: “A man is used up by the end look at my wings.” The concluding line of a brief poem with otherwise short lines and enjambment stretches out, winglike. This can be jarring at first, but I think you quickly get used to it when you read the book because he does it so much. It’s strange, but I’m fine with my reader having to work a little. These are not easy poems. I don’t expect readers to “get” them on the first try.

AD: Gracias, thank you Lucina for the interview, and for your valuable efforts of bringing Miguel Ángel Bustos to a new audience!

***

Endnote on the origin of “Voseo” in Spanish: the term “vos” comes from the colony, a second-person form once used to address what could be at once a singular and plural audience, it was developed by the creole or Spanish authority-figure to address the native subjects as neither “tu” (too personal to say to an indio) nor “usted” (which is too respectful, a “thou”). “Vos” is uttered with a certain rasp. — Artu

Arturo Desimone, Arubian-Argentinian writer and visual artist, born in 1984 on the island Aruba he inhabited until the age of 22, leads a nomadic existence, was recently based more in Argentina while working on a long project. Desimone’s articles, poetry and short fiction pieces have previously appeared in CounterPunch, Círculo de Poesía (Spanish), Moko Magazine, Drunken Boat 22, Acentos Review, New Orleans Review, “DemocraciaAbierta.” A never-produced play he wrote was published in serialized form in the world-lit journal of University of Istanbul until the latter was shut down. His translations of poetry have appeared in Blue Lyra Review and Adirondack Review.

Notes on a Return to the Ever-Dying Lands was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.