Hong Kong is simultaneously colonized (by mainland China), post-colonized (by the British), neo-colonized (by global capital), and Disneyified (by America). It is a pivot point, an intersection, a node funneling feed to every modern day Leviathan. In turn, protests are answered by kidnappings answered by upper-class self-exile and lower-class occupation.

So, the global phenomenon of migrant domestic workers coming from South Asia, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, and now Cambodia, is for the most part a non-issue in Hong Kong. Like the space itself, attitudes towards domestic work are contradictory. Some see it as a feminist ideal because these workers allow local women to remain in the workforce even after giving birth. Meanwhile, the South China Morning Post publishes op-eds claiming migrant workers are slaves, and Hong Kongers the slave owners — an assessment that Amnesty International also agrees with. Here are facts:

1) Foreign domestic workers number 4–5% of the population and make less than half the minimum wage ($564 USD a month). Research shows that very few employers pay above the required minimum.

2) Foreign domestic workers are required by law to live-in with their hosts, and there are frequent reports of having to sleep in very tight quarters (in kitchens, in cabinets) with no privacy.

3) Foreign domestic workers are required to work for six days a week, and have no off-time in between except to sleep and eat.

4) According to Justice Centre, 1 in 6 have been subjected to forced work, physical abuse, mental abuse, or sexual abuse.

These sobering statistics are obscured through the daily language used to discuss domestic workers. In contracts, law and local media they are referred to as “helpers” rather than “workers,” which erases their job training and the skills required of them. Their living conditions, according to law, must be “suitable,” a bizarre term that basically translates into “whatever you feel a brown foreign woman can survive in.” Like the many crossovers of Hong Kong colonized space, domestic workers also fall into multiple intersections: womanhood, brownness, poverty, religiosity, sexual obedience (matronlyness), and foreignness.

All this in mind, what can we expect from artworks inspired by the struggle of migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong? In the past two years there have been a spate of artists, organizations and curators hoping to shine more light on domestic work, and in the past I’ve spotlighted artists who have sought to capture the hypocrisy and cruelty of domestic work, and written some fiction of my own that attempted to do this. Below I look at three recent artworks — two documentary films and a chamber opera — where domestic workers appear as muses meant to inspire the song and dance of tragedy.

1) “The Helper,” (2017)

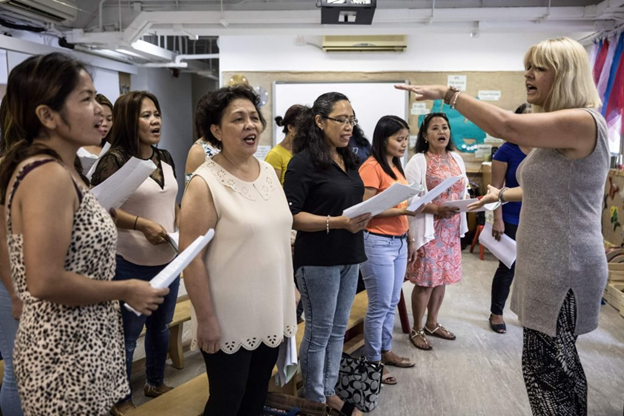

The 2017 documentary, The Helper, directed by the British Hong Kong-based filmmaker Joanna Bowers, follows migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong, “helpers” who strive to “rise above” their expected service roles. The film focuses on The Unsung Heroes, a choir of domestic workers founded by a British music teacher, Jane Engelmann, head of performing arts at The Peak School, a colonial-era (1911) Hong Kong English primary school. Driven by her love for her own children, Engelmann seeks to help the “helpers” find their voice by writing songs for them to sing about missing their children back home (“Kiss You Goodnight”), and about celebrating their “voice” (“Find Your Voice”). The film ends with each “helper” reaching the peak of liberal success: wearing the choir name, “Unsung Heroes: Find Your Voice, Sing Your Song,” on bright blue T-shirts, singing Engelmann’s hymns as Engelmann herself conducts them, their voices pleasing a crowd of local Hong Kongers and expatriates at the biggest music festival in Hong Kong, Clockenflap.

In an interview, the director Joanna Bower claims that her inspiration for The Helper came from feeling “fascinated by the visual spectacle of thousands of domestic workers sitting out on the walkways in Central.” Ironically, the film itself seems uninterested in domestic workers who occupy public space on Sundays, as one of Bowers’ interviewees says, her employer told her not to sit with other Filipinas in public space: “for me, it is degrading, [so] go somewhere else.”

Bowers credits her own domestic worker, Janai, as her main muse, a woman whose mother was also a domestic worker and since coming to Hong Kong has sought ways to “make her mum’s incredible sacrifice worthwhile.” Domestic workers, in Bowers’ depiction, levitate with the sanctity and maternal sacrifice of Mother Mary — appropriate when so many are presumed Catholic. But as scholars have pointed out for years (Denise Cruz/Anna Guevarra/Harrod Suarez), less than half of Filipina overseas workers identify as mothers, and presuming that every Filipina worker is a natural mother has remained a vicious stereotype that degrades the training and work that they do. Bowers’ film is no exception. Her most frequent subject, the teacher Jane Engelmann, describes her “cause” as showing to the world “that these women are not workers, not Filipinos, but mothers.”

2) “Sunday Beauty Queen” (2016)

Similar to The Helper, Sunday Beauty Queen (2016), also documents Hong Kong migrant domestic workers, but from the point of view of its Filipina director, Baby Ruth Villarama. Winner of the Best Picture award at the Manila Film Festival, Sunday Beauty Queen follows a group of domestic workers and organizers as they prepare to put on an annual pageant of beauty queens. The narrative juggles stories of workers who spend their Sundays walking runways, dancing, and inspiring donations for other community projects. Speeches by the beauty queens overwhelmingly mention their children in the Philippines, and their gratitude to employers and the space of Hong Kong for hosting them. Even so, Sunday Beauty Queen is eye-opening and, unlike The Helper, celebrates the communities that migrant domestic workers have built, including the occupation of public space. Perhaps this is because Villarama dedicates the film to her mother, who was once a domestic worker in Hong Kong. The film also takes to task the lack of protections by the Hong Kong government, the greed of the employment agencies who drive workers into debt, and the risks of abuse, rape, and suicide.

Despite the film’s success, Baby Ruth Villarama has been criticized for not paying talent fees for her actors. Her main subject, the community leader Leo Selomenio, was not paid at all for her performance, and it has been suggested that neither were any of the domestic workers who appeared in the film. All of this could perhaps be excused by Hong Kong law, which requires that domestic workers not take any employment outside of their contract. But in response, Villarama does not mention this law. Instead, she suggests that the film’s mission to depict migrant workers positively is in itself a form a payment, giving credit to “the blessings and support our Sunday Beauty Queens have been receiving post the screening of the film, [who] very much deserved it for all their hard work and sacrifices.”

Here is where the artist betrays her own muse. The “helpers,” stamped with the sanctity of sacrifice, cannot be paid as if they were professionals, workers, employees, because to do so would break the spell. It is the same spell that Liisa Malkki, in her book The Need to Help, saw in Finnish Red Cross volunteers when they unconsciously relegated their subjects into “the needy,” people who should be happy once their basic needs are met, who should remain distant and socially anonymous, who should not expect pay (because money must be earned not given), and who must fade from the giver’s life once their needs are met.

Though I don’t believe the scandal of talent fees defeats the film’s charm and its potential effects to raise consciousness concerning domestic workers, it does raise a question at the heart of the gendered/racial/sexual crossovers that these workers encapsulate: Is the artist just another boss? Can your muse also be your employee?

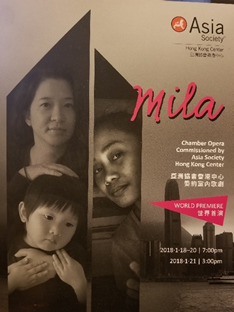

3) Mila (2018)

Mila was a one-hour chamber opera held at The Asia Society about the plight of Mila, “a domestic helper from the Philippines hired by a family of three in Hong Kong.” Its placard reads: “New to the city, Mila remains hardworking, patient and determined to please her employers despite their fussy and negative attitudes.” These “fussy” attitudes include having fired their previous twelve maids, and wanting to chide Mila for not being able to fry an egg or toast bread, even after she has worked as a maid in Singapore for 20 years.

The family consists of an adulterous white father and a tiger-mom Asian mother who both feel miserable living in Hong Kong’s “concrete jungle” despite their immense wealth, and who both complain about their “incompetent staff.” Their son, nicknamed “Little Master,” is stressed from the demands for high grades, and gravitates towards the balcony, which Mila takes to mean he is suicidal. With an ending reminiscent of Madame Butterfly, the suffering, exploited Mila commits suicide by throwing herself over the balcony, sacrificing her life for the life of the family’s child.

The opera’s libretto writer, Candace Chong, thought of writing Mila after she was asked to write an opera celebrating Hong Kong’s ethnic diversity. In so doing, the opera, as the Asia Society stresses, does not paint “Hong Kong in a negative light,” but instead depicts Hong Kong society as “triumphant.” The producers seem determined that the opera not be seen politically, that it not feel like its “indicting” Hong Kong at all, but that it shapes an “important social issue” to show how “arts can transcend news.”

When the Muse Makes Demands

Based on these three artworks that seek to marshal sympathy for domestic workers, one would think domestic workers had no political voice in Hong Kong, and that artists, choir directors, and libretto writers were tasked to give voice to them. But domestic workers do have a voice, and many of their artists and writers have been active for many years, some winning big awards, and their work has had political rippling effects that go far beyond asking for “voice” and “appreciation” from locals or expatriates. A protest organized by a coordinating committee of multiple domestic worker groups in September 2017 made the following demands:

1) Increase the monthly minimum wage by 27.6%

2) Raise the food allowance to more than double (to HK$2,500 per month)

3) Scrap the “live-in” rule requiring workers to live with their employers

Can we hear this “voice” when it does not speak with the muse’s sacrificial hymnals, but with the inconvenient, indicting refrain of dissent?

Are Foreign Domestic Workers The Muses of Hong Kong? was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.