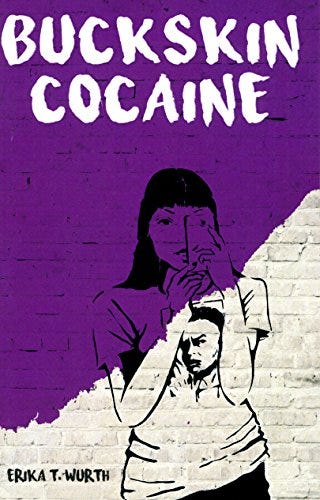

Erika Wurth’s Buckskin Cocaine is a collection of seven interconnected short stories and one novella, centered around a fictional Southwestern Native American film festival. Each selection is told via monologue of one specific character who works in film or runs in an entourage of one of the multiple film industry personalities. One thing you can count on in creative industries is finding the tribal folks hanging out together, and in industries that can be brutal to non-white professional folks (like film) it makes more sense that Natives stick together even if they don’t necessarily have much else in common.

The characters within Buckskin Cocaine are flawed in many of the same ways and hold more in common than what may be visible on the surface. We meet directors, actors, models, dancers, writers, wannabes, and self-important fame-seekers. As one would expect with a collection involving film industry professionals, a focus on image, sexual attractiveness and prowess, identity, youth, and changes in personal social stature show up within each narrative. Shallowness, cattiness, and narcissism abound. Addictions, dysfunctional families, broken relationships, swollen egos, and personal insecurities all feature within the collection’s narratives as well — sometimes all within the same paragraph. Yet, the seven main characters are each distinct, dynamic, and interesting. Each show various levels of honesty and self awareness in their monologues. We gather more context of each in the observations and scenes mentioned by the other characters when telling their own tales. Classic excesses considered a requirement of artistic/celebrity temperament, current/childhood poverty issues that manifested in odd habits or violent tendencies, other people’s shortcomings or viciousness, and a constant pressure to be more _______ (available / exotic / rich / talented / Native / traditional /etc) are all considered reasons for a character’s epic downfalls or lack of success. It’s hardly ever seen as their own doing unless from afar.

Some characters, like Candy Francois, are so focused on the surface level of their life and their past that they repeat the narrative they want to hear. “I was in my early twenties, I was a model, I lived in New York,” is the refrain this character keeps repeating like a record needle scratching the same vinyl surface leaves only one audible piece of a song. However beautiful that audio may be, it’s not the entire song. It’s obvious to all the listeners that something here is broken.

Because of their similar character flaws, the connections these people find with one another become all the more intense and potentially destructive. One example of this comes in the friendship between George Bull and Robert Two-Stories (film directors held in different levels of esteem by the industry). While they both benefit from their friendship, it is glaringly obvious to everyone that they do not bring out the best in one another and are constantly disappointing one another. Being together fuels both men’s misogynistic tendencies, dominance posturing, drinking, and drug use. Neither shows anyone else in their circle as much respect as they show to each other. Each treats the tertiary relationships talked about or formed by the other with disdain. While both have huge commitment issues in sexual relationships, they have stayed connected to one another for years without holding the same types of grudges they form against their sexual conquests. This makes the introductory observation by Candy that the two went around together “like a married couple” seem quite astute. The only person either can commit to is another version of themselves.

The culminating novella, told from ballet dancer Olivia James, develops many of the themes that appear in the earlier stories. This is where Wurth deftly explores what professional artist ambitions can mean for working-class women. The type of ambition that strains the relationships you have with every person you know. The lack of support, understanding, and resources needed to do what you know you can accomplish, even from people you love. How potential career advancement must come at the cost of all else — family, relationships, and comfort foremost. The chutzpah it takes to continue forward. She leaves us meditating on where you go after you’ve progressed as far as you can professionally but no longer fit into the spaces you once inhabited or the new world you’ve built. The answer, of course, is found in the cinematic trope of walking into the sunset.

Erika Wurth’s Buckskin Cocaine is a collection of seven interconnected short stories and one… was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.