Kia ora!

That’s hello in Māori, the Polynesian language spoken by the indigenous Māori people of New Zealand. Te reo (“the language”), as it is also called, is an important part of expressing and maintaining Māori culture and identity. We just rounded off Māori Language Week, an annual celebration of the Māori language. In New Zealand, there were language parades, exhibitions, and other festivities throughout the week.

Māori was the primary language in New Zealand until an influx of English settlers in the mid 19th century made it a minority language. English-style school systems pushed Māori out of the curriculum and forced many Māori people to learn English. While some Māori people maintained the language in their homes, the number of Māori speakers declined. Māori leaders feared that the language was at risk of disappearing. ,

In the 1980s, language recovery programs like the Kōhanga Reo movement encouraged more children to learn how to speak Māori through immersion. Māori leaders petitioned the government to take measures to protect and promote the language; Māori Language Week is part of that revival effort. Thanks to the Māori Language Act in 1987, Māori is recognized today as an official language of New Zealand.

For those of you interested in learning a little Māori, here’s a resource with some basic vocab in te reo Māori, including sound clips for pronunciation.

In addition, if you’re interested in exploring Māori music, this website has compiled Māori folk songs, or waiata, with lyrics translated into English — and even chords and videos! Here’s one popular song from the site, “Tiaho mai rā”:

For readers keen to find Māori literature — Jacket2 has published two profiles of some recent Māori poets, one post highlighting women writers, then a second featuring male writers. These two posts give a taste of the rich landscape of contemporary Māori poetry. For instance, poet Apirana Taylor raves that “Māori poets whether writing in English or Māori are, at this time, writing some of the finest poetry ever written in this country.” However, the articles express concern about its marginalization within New Zealand’s literary scene. Māori poet Rangi Faith notes with urgency, “There are a number of young Māori poets being published but I think you have to see the statistics to really understand the position of Māori writing in the [New Zealand] literary community. It is low — some researchers believe up to 90% of published work is by European writers — leaving about 3% for Māori. If there’s a need — that’s where it lies — in the publication of more Māori poets and writers.”

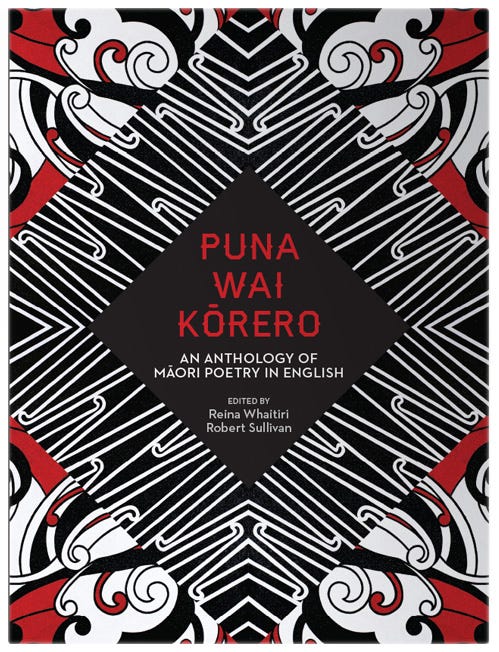

And as Reina Whaitiri expands, “If and when Māori poets are included in Pākehā anthologies they are not usually given the respect and acknowledgement they deserve.” She decided to take action and, together with Robert Sullivan, put together the first ever anthology dedicated exclusively to Māori writers in English: Puna Wai Kōrero (2014).

Here’s one poem from the book, Hinemoana Baker’s “Te tangi a te rito”:

Bones, in this place the soles

of my feet are not null; how

must I walk? My throat

has not woven the call. My throat

has not spoken the harakeke. The north

you say, is thick with it.

Open-mouthed for the host but not

so silenced in the throat. In this kitchen

violence placed its thumbs on the bud

of the call. In this garden violence

pinched us back.

The softness drops

from your forehead, shame

darkens my mouth to a

museum, to a purple

gallery of pūhā and pāua and the sounds

of these things

that keep a family well-fed

and its friends

at your table in the singing

summer.

Whether or not you live in New Zealand, you too can join in celebrating Māori language and culture.

Māori Language Week was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.