I’m ecstatic this month to interview Robert Yang, the Asian American game developer responsible for erotic, intimate queer games like The Tearoom (a “bathroom sex simulator”) and Rinse and Repeat (a “male shower simulator”). You can play all of his games on his website for free (or with a voluntary donation).

Robert is also an Assistant Arts Professor at New York University’s Game Center, and has an article in the new anthology, Queer Game Studies.

He’s been interviewed by mainstream journalists in The Guardian, Kotaku, Rock, Paper, Shotgun. I read these interviews, feeling that they spoke little to the radical feelings of Robert’s games: how playing them feels as liberating as finding “the right position.”

So as both a scholar and an artist myself, I asked Robert questions that straddled the line of the academic and the artistic, the blustering and the indecent, the genteel and the invasive. At the risk of embarrassing us both, I’ve reproduced our interview unedited (I’m not a real journalist, remember):

Kawika Guillermo: Thanks for agreeing to speak with me. For starters, what brought you to be interested in game design?

Robert Yang: I played a lot of video games growing up, and some of those video games came with tools and editors that let you modify them / build on top of them. As a modder, it was invigorating to interact with that existing audience — there’s also a shared subculture with other modders.

Guillermo: We’re living in a “golden age” of indie games, and many recent entries have been attempting to tilt games more towards representations of marginalized groups. Do you find your games have similar goals?

Yang: Well, maybe we’re not living in a golden age of video games? Many indies argue we are in an “indiepocalypse,” where the economics of making indie games are crashing. Their goals are to carve out their own niche in the market, and to sell enough copies for sustainable game development — but as for my own games, I lost confidence in their marketability a long time ago, so I took up a day job as a teacher to support myself instead. Since I’m not trying to cultivate a specific fanbase, I’d say I’m interested more in mapping systemic boundaries and barriers in games.

Guillermo: I’m thinking particularly of games like Coming Out on Top and Dream Daddy, as well as games by merritt k. How do you see your games in relationship to an expanding genre of “queer games” which sometimes count AAA games like Mass Effect?

Yang: I think my games fit neatly into a “queer games” genre, but at the same time, also like merritt, I’m a bit suspicious of the political implications of classifying us as “queer games” — as if we’re being shuffled into our own queer games ghetto, separate from “normal games” — or if assimilation isn’t our goal, then we also don’t want to be qualified / quantified by normative games, etc.

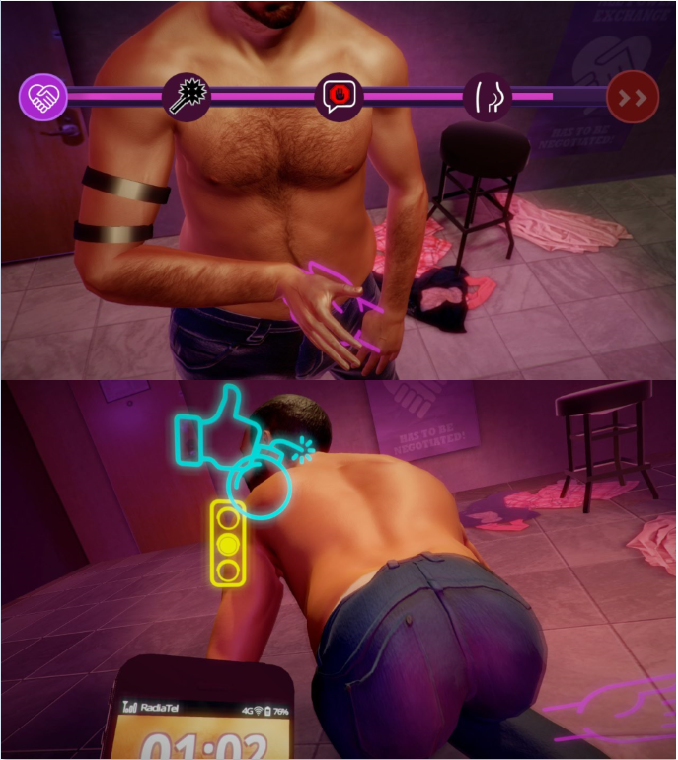

Guillermo: Much of your work, like the small games in Radiator 2, push the mechanics of games towards more erotic and intimate engagements. What are some techniques you’ve used to do this?

Yang: Radiator 2 is a lot about “game feel.” How does it feel to interact with the video game? To try to make a game feel more intimate and expressive, I try to use “natural” input mappings — the gesture you use with your mouse in real-life mimes the virtual gestures performed in the game. So, spanking in Hurt Me Plenty involves fast forceful mouse movements, while Stick Shift requires you to pretend your mouse is a gear stick and move it in a similar way. These are simple gestures that hopefully do not require too much explanation, because I think over-explanation ruins an intimate mood.

Guillermo: One of your games, Cobra Club, is censored from being shown on Twitch. Why do you feel that such a high level of violence is permitted on game channels, but not sex?

Yang: Twitch bans my games (and many other games) because gamer culture wants it, and that complicity means video games are ultimately still for children. Normative masculinity (especially white masculinity) allows men to be serious Mr. Big Men deserving of power and weapons, while also being “good kids” who should be protected from consequences of committing sexual or racial violence. This double standard is aptly expressed by the term “man-child”, and gamer culture is invested in preserving this man-child identity. In order to maintain that fiction of innocent childhood, at least in the US, that involves banning sex — unless it’s a large company commodifying sex, then Twitch conveniently understands their artistic intent and never bans them! Meanwhile, I’m trying to make games that “earn” their sex, not just for titillation, but to try to explore the design space and aesthetics… and for that, I’m punished with a ban. It is also not a moral stance, because they apply it so inconsistently; rather, it is a nihilistic capitalist stance devoted to enshrining patriarchy.

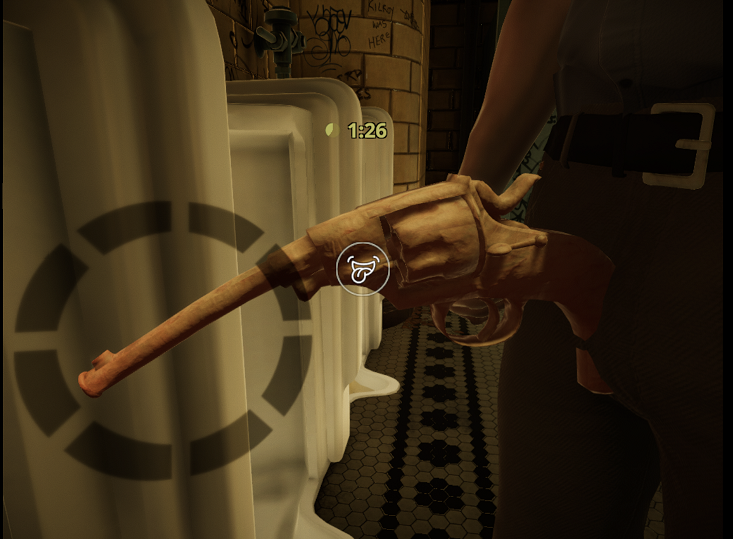

Guillermo: Your games Stick Shift and The Tearoom both feature police authorities who break up queer pleasure (in the cast of Stick Shift, masturbating a mid-sized sedan). At the same time, 2017 was yet another year when pride parades were stifled by the presence and “alliance” of local police. Can you talk about this theme in your work?

Yang: A common theme among US LGBTQ activism has emerged in recent years: we need to remember that Stonewall was a protest against police brutality, and we need to re-center trans rights / re-align intersectionally with other movements like Black Lives Matter. It made me realize how police function in video games — even games like Grand Theft Auto position the police as fun entertaining “fair” partners in play. If we were to translate a BLM argument into procedural rhetoric, video game police should function very differently. Maybe police should be more like what Johan Huizinga calls “spoil-sports”, people who break the game and punish you for your involvement. It is about imagining a different way of aestheticizing police in video games, in line with contemporary intersectional politics. (And the car in Stick Shift is gay, by the way.)

Guillermo: I’ve interviewed Minh Le (creator of Counter-Strike) on this blog and yourself, though I’ve sent invites to many other Asian-heritage designers, some of whom seem to back away once they understand that I’ll probably ask them about their background, or about race in their games. I understand games are collaborative, and that so often marginal voices are stifled, but do you find that there is less of an urgency — or perhaps less desire — for developers to represent their identities in games?

Yang: Speaking as an Asian-American of Chinese descent, first there’s just a big problem with education. No US school taught me or my friends about Vincent Chin or Yuri Kochiyama; we spend 5 minutes on the Chinese-Exclusion Act, and 1 day on internment. We weren’t “important” or “interesting” enough to merit more time, and it’s sad but understandable that someone would have nothing to say about it. It’s not just shame (which is very Asian, haha) but a particular shame that you know nothing about this aspect of yourself, and then another layer of meta-shame about being ashamed of knowing nothing.

I grew up in a white US suburb, so I was never socialized into thinking my race was important. But when I came out and got into gay culture, I realized that other gay men were treating me differently because I was Asian. (Turns out my sexuality was connected to my race, wow!!!) So here’s the problem that me and many other young Asian-Americans face now: we have some consciousness about our identity, but now what? What are we fighting for, who are our leaders, how legible are our politics? If I were to make a game about Asian-American issues, what does that even look like, what work is that supposed to do? I’m trying to listen and figure that out.

Guillermo: I’m frequently in conversations with Asian American scholars, whose only knowledge of Asian Americans in gaming are games like Sleeping Dogs or characters like Faith from Mirror’s Edge. There seems to be very little knowledge of the developers who make these games. Why do you suppose this is?

Yang: As a general rule, AAA game developers will not talk to anyone on-record unless they’re promoting something, and after they’ve been trained / coached not to say anything “controversial.” It’s a mixture of capitalism demanding a profit motive + fear of gamers harassing them for any imagined slight against their sense of consumer entitlement. But more specifically about Sleeping Dogs and Mirror’s Edge — both of those games were made by teams of mostly white people in Vancouver and Stockholm — they probably think of their Asian characters as unique selling points to appeal to a globalized market. It’s unclear how much thought they actually give to their characters’ identities as politics. But personally, I’ve often been disappointed by my conversations with industry developers about this anyway, so maybe Asian-American scholars aren’t missing much.

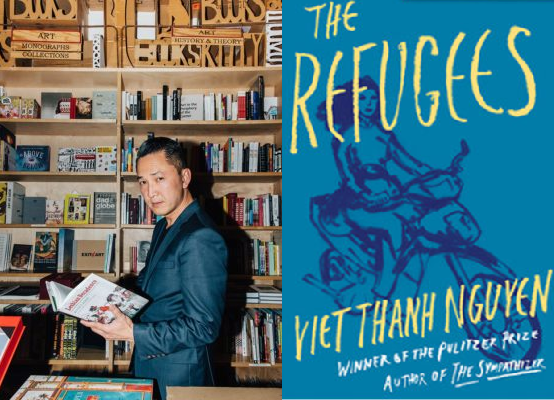

Guillermo: One reason I’m so interested in Asian-heritage designers, is that as a hapa fiction writer, I have to heavily consider how my Filipino/Hawaiian name (Kawika Guillermo) will translate to my audience. As writers like Viet Nguyen point out, writing under an ethnic name will often “pin down” the creative work into a kind of ethnic literature, and imply certain conventions (first person, authenticity). Do you find a similar role for yourself as a game designer? Or do you find more freedom without these expectations?

Yang: I haven’t made any games specifically about my Asian identity yet (see response 6) but in video game land, these expectations don’t even exist because hardly anyone makes “personal games”, and even when we do, conservative reactionary gamers attack us for “injecting politics” into games, as if games aren’t political artforms already. Video games have existed for decades, but only in ~2006 did Roger Ebert popularize the “games as art” debate in the public sphere. There is no deep centuries-old literary tradition here. Instead, we’re desperately trying to reverse-engineer art out of capitalism. So while I sympathize with your problems and concerns as a hapa fiction writer, I’d also love to be in a place where I have those problems, because that would mean video game culture had finally evolved to that stage.

Guillemo: You recently contributed to the anthology Queer Game Studies, with a chapter on the game Dead Island. Can you describe what let to this anthology, and how queerness is usually perceived within the games industry?

Yang: That book came out of the first Queerness and Games Conference in 2013, where I also presented. There was a conscious move to reify what we were doing, to make it more real. This instinct for preservation is something that games culture is terrible at, but academia is good at it. Years later, the book is finally finished, thanks to the hard work of the editors Bonnie Ruberg and Adrienne Shaw.

As for queerness in the game industry, most of the game industry in the West is 18–50 year old straight white cis-men. I’m not sure how much thought they’ve given to queerness, if any. Collectively, the industry understands that queerness drives a lot of fandom for games like Overwatch, but individually, I imagine most industry developers are noncommittally supportive and/or secretly hostile.

Guillermo: Lastly, What is your hope for the future of games, their designers, and their players?

Yang: To survive.

Robert Yang is currently an Assistant Arts Professor at NYU Game Center, and he has given talks at GDC, IndieCade, Queerness and Games Conference, and Games for Change. He holds a BA in English Literature from UC Berkeley, and an MFA in Design and Technology from Parsons School for Design.

Kawika Guillermo is a fiction writer whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Cimarron Review, Feminist Studies, The Hawai’i Pacific Review, and others. By day, he’s an Assistant Professor of Humanities and Creative Writing at Hong Kong Baptist University. Tweet him @kawikaguillermo

Robert Yang: “the car in Stick Shift is gay, by the way” was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.