In Tori Amos’s defiant 1994 dirge “Cornflake Girl,” the narrator wails a lament from the liminal space between pain and dreams, or history and memory. It is a lament for a specific kind of pain, pain with its origins in betrayal between women, pain with its origins in love, pain whose exact locus cannot be identified because of the screaming denial in your own head as you suffer, chanting “this is not real/this is not really happening.” Predictably, that line occupies a lullaby place in the midrange where nearly any voice can reach, and the response comes in an operatic crescendo that few can sustain without breaking: “you bet your life it is, you bet your life it is, you bet your life…”

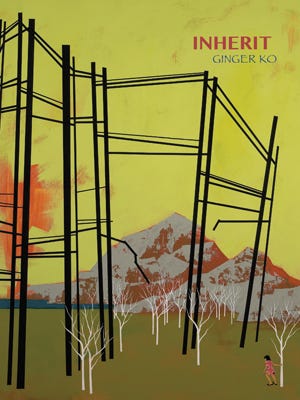

In Ginger Ko’s Inherit these two voices, the glass-shattering truthsayer and the soft chant of denial, sing not in alternance but in unison. This is a hard thing to do, and Ko does it with a kind of ruthless and understated precision that makes the reading of Inherit both absorbing and uncomfortable. Just as in Amos’s song you are listening to someone else’s pain in a way that erases distance and decorum, in this book you are not invited but required to bear witness to a difficulty that is generational, historical, and personal, and in which the speaker… is often both victim and aggressor. Much of Inherit reads like a catalog of grievances for which the book issues a firm j’accuse, and you should not be surprised; though much about this book is beautiful, nothing about it is pretty or easy.

The first poem, “1930–1963–1984,” delimits the historical scope of the stories that interweave through this book and plants a defiant flag in the moon (moon, water, blood, womb, effluvia, mother, family tree) territory: “I don’t care what / freedom has led you / to believe — this blood is for testament.” It’s an intriguing beginning whose deliberateness of structure is repeated in this first and bigger section, “Lacunae,” of the book: like a Bantam Dual-Language Edition, you have on the left side of the page a poem in verse and on the right a prose piece entitled “transl.” Because of the first-person pronouns that seem to occupy the left-side pages, and the third person that invariably occurs on the right, it is easy to read the verse pieces as Ko’s personal experience and the “transl.” pieces as her renderings of family history, a series of vignettes about the lives of a grandmother and/or mother (as notable for what they omit as for what they declare), but this would be too simple; Ko’s “I” has an air of polyvalence, if not omniscience, and its experiences range too far and wide to be contained within one body. Recto and verso form an extended and carefully ambiguous set of narratives whose unified voice masks their radically different places and times, and whose reading requires you to hold the possibilities of three generations and two continents in your head. You could assume that the left-and right-hand pages should be read in tandem, as some kind of translation of each other, but this would also limit your capacity to notice connections between and across pages, as the voice flickers between generations, seeming always to land back on the same question: “if you birth them wouldn’t they all / be mad” and “why did you do it / let it happen / what did you hope would happen to me.”

That interplay alone makes the book demand a second, third, and fourth read, until you can let the different moments and glimpses settle into something resembling connection (if not chronology) in your head, until you have a sense of the palette if not the particulars of Ko’s landscape, and of the angle of her gaze as she observes “the unseen space from which a mouse is shrieking.” Mouse, indeed — this line perfectly captures the tiny quotidian horror of so many of these moments: the obligations, the disregard, the erasure; the self-assertion that comes out twisted, the violence so faint and yet so clear, like a tiny animal’s shrieking, that it is only in seeing it named, alone on the page, that it must be acknowledged, and yet Ko includes so many other violences — of neglect or aggression, of grief or fury — that all of these indignities and oppressions seem to hang from a balance of equal weights and intensities.

This is not an easy feat. Imagine one of those mobiles that spin above a crib, glittering and twirling to catch the light. Imagine that the objects suspended are made of blood and memory, and inheritance of difficulties and dolors. Ko has balanced them in such a way that each floats wrapped in quiet and each connects to all the others. As one of the transl. poems simply reads, “legacy.” This is a catalogue and a testament and the persistence and honesty of Ko’s “I” mesmerizes: “I am often weak / cannot stop myself / and am afterwards appalled.” Still, Inherit is unabashed, at the end of section one introducing a first person into the right-hand page with this resolve: “To stop letting others buy shares of me.”

In an interview with Grace Shuyi Liew, Ko asserts, “I hope, if I’m working with any genealogy, it is the feminist tradition. Writing as a woman first.” Consider this aim achieved by Inherit. The book concludes with “Sequellae,” unifying the text into one long lyric that seems to assume and absorb all the sharp edges and dull aches of these many voices. Not to resolve them, but to finally declare, “my ferocity is neither empty / nor punishing but that / is not happiness that is strength.” Inherit is a manifesto, a birthright, a chorus of all the difficult truths that make a family. You bet your life.

Inherit: the Floating Lives of Ginger Ko was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.