Arturo Desimone’s series on Latin American poetry, for Anomaly (previously Drunken Boat)

The Invitation to a Latin American Young Poets Encounter in Cuba shortly after the Death of Comandante :

Part 1 of a Report on the “Encounter of Young Latin American and Caribbean Writers’’ in Havana, Cuba

Zenófono said he was a scout for the literary institutions of Cuba, that he worked for Yiurielis and for Dulce María Loynaz, and the renowned “Casa de las Américas.”

The scout had found me on the internet. Messages came on Facebook, showing a picture of the young man in a doctor’s coat and thick glasses. He explained that he wrote medical thrillers, tales related to his experiences in the field of oncology.

Zenófono is a Cuban doctor. Originally his name was the more French Xénophone: he hails from the Franco-Haitians who settled Guantanamo. He left Guantanamo after his pre-med studies, and was struggling in the prestigious educational programs for young specialists to champion medicine and public health (often for export to treaty countries), as well as in the literary world. After internal migration to Havana, he discovered he could develop his interest in literature far from the fruit-bearing valleys of Guantanamo, inserting himself into the employ of myriad cultural organizations, enrolling in seminars given in Cuba by José de Saramago, visiting Portuguese author of Planet of the Blind and a winner of the Nobel prize. He was also a workshop student of Luisa Valenzuela, Argentinean novelist and survivor of the dictatorship’s ESMA camp after she was blacklisted. (Zenófono spoke euphorically of coincidences in our shrinking world: I admitted that I also met Valenzuela during the time I sought employment in today’s Argentinean cultural resistance.)

He had never seen the high gray walls of fort Guantanamo Bay, which stood far removed from residential areas of the Guantanameros. Zenófono was a die-hard “Argentinophile”, even capable of speaking in mimicry of the distinctive Argentinean accent. He knew all the works of Argentinian and Uruguayan writers from the 20th century, from the Ocampo sisters Victoria and Silvina to Ida Vitale and Idea Vilariño, and romanticized Argentinean-Uruguayan girls both for their literary and suicidal tendencies, he would cite them when walked the boulevards of Vedado chilled by the last days of tropical winter, passing Argentinean tourists who carried their mate-herb drinking equipment and t-shirts in political colors.

In our first conversation on the internet, Zenófono told me we were to become the greatest friends. During his birthday, he logged in with an internet-ration card, asking me to congratulate him and to give good news, a confirmation. Havana is exuberant he said. I had only been to Cuba once, accompanying mother on a business trip to meet cigar-rollers and other state employees in tobacco; we intended to bring Cuban cigars back to Aruba, our home-island, to sell to American tourists who demanded in their distinct voices that they wanted ‘’real McCoy and no knockoffs’’. (We had sold mostly counterfeits, and the aggression of the American tourists, their ruddy faces burnt by sun and mixed drinks, smelling of more than adrenaline and suntan lotion, were intimidating. It was time, mother hoped, to make our business on Aruba finally legit and to stop selling Dominican products with fake Cuban rings and stamps on them. But I told none of this to Zenófono, not even of the girl of 13 I had met when I was 11 in Habana in her family home as I watched her do her math homework in her pioneer-scarf. First I needed to know just who I was talking to.)

— You better watch your money, Zenófono warned, adding that he knew how much of a temptress She, capital of the tropics, Havana could be, unto any “Yuma’’ or foreigner going out in the old town, de pronto aparece una bella mulata y ¡ ciao dinero! (the apparition “bella mulata’’ would signify “ciao dinero’,’ I memorized the equation). He spoke as a physician, explaining the effects of a certain drug or the glowing symptoms of a strange illness affecting the aorta or the foot (my knowledge of oncology was and might forever remain limited, even zero).

Zenófono promised that he would bring me to the house of Dulce María Loynaz, and to the museum where I could see one of the largest collections of ornate hand-fans and petticoats in the Caribbean. I did not understand why the doctor presumed that I had any interest in a collection of such quaint artifacts, but I feared offending the scout, who seemed pleased with his plans for all the wonderful activities we would do together. I had not yet received the official invitation.

It was a strange haunting moment to be invited to Havana, capital of the tropics, coinciding with the death of the titan, the most famous guerrilla of all equatorial nations, Fidel Castro, two months before the book fair. I packed lightly, taking only Argentinean books that my host Zenófono requested; Cuba is famous for the wide availability of affordable books (one of the pillars of the revolution is made of books.) I planned to bring back a small library from the island. A stack of my own “Letters to Karl Marx and Other Poems’’ would be handed to me during the festival by a visiting Peruvian writer who brought the package from my publisher in Lima. The series of poems I would read from in Spanish and in English began as my mocking response Karl Marx’ love poems for his wife Jenny, but they grew into a further-reaching critique. I left early for Cuba, 5 days before the festival.

A few words the Dulce María Loynaz, the namesake of Centro Dulce María Loynaz (the latter one of Zenófono’s employers, the former, one of his heroines)

Centro Dulce María Loynaz was named after a grand woman of Cuban letters, Dulce María Loynaz, who wrote “in my verse I am free/ my sea broad and naked of horizons’,’ is said to be one of the early postmodern “intimista’’ or intimacy-seeking poets of the language. She immortalized that 20th century baroque bourgeois culture of Cuba. Loynaz stopped writing and publishing decades before her death and before winning the most prestigious prize in the Castilian language (the Miguel de Cervantes prize). “My epoch had passed’’ había pasado mi época declared with hiraeth (term imported from Welsh, hiraeth, means nostalgia for a place that no longer exists or never was. Tonight we are on the prow of the steep time of unending hiraeth, and every toast for a completed journey is Pyrrhic).

Dulce María Loynaz’ first novel was Garden, (Jardín) and she took 7 years to edit it; her next work was a travelogue-epic Love Letter to Tut-ankh-Amun, a chronicle of her journey to Syria, Egypt, Tunisia, Palestine and the Gulf.

Many of the founding, patriotic poets and writers of Cuba were female contemporaries and comrades of José Martí as well as of later generations, such as the scandalous taboo-smacking Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda (19th century) as well as Josefina Nuñez.

In Havana, I would read at the Casa de la Poesía, located in the middle of the old city of Havana, near the Mercaderes street where the young intellectuals, poets, financiers and leaders of the first patriotic Cuban revolution after the abolition of slavery had once gathered — poets like José Martí, Gertrudis Gomez de Avellaneda, and other members of a fascinating bourgeoisie, who met there dressed in their Friday evening finery, and who would lose all their wealth, but none of their spirit-saddled elegance during patriotic uprisings against the Spanish and against the Yankee.

Such a vibrant, politically engaged, cultured section of the Cuban nationalist bourgeoisie of the later 19th century and early 20th century existed. It included members of bourgeois families who had supported abolition of slavery prior to the Independence struggle, and against their own profit interests. They upheld a baroque culture of feverish letter writing, polemics, and salons. (Others, of course, supported imperialism and the ruling juntas.) The patriotic-bourgeois nationalist resistance to Spain and to the emerging US/Union imperialism, is best exemplified by José Martí, the inspiration today for all Cubans who combine journalism and literature with politics, (regardless of their position on the Castros). Cuban liberals were intellectually and morally capable of relinquishing their own properties as the price of standing up to the powers of Spain, to invest in revolts.

Inevitably, such a culture outlasted the thuggery of military dictators to come, such as the dictators Machado and Battista, until the full flowering of the revolution, in which part of the Cuban middle class had sustained the tradition of their forerunners at tremendous expense, and often disappointment.

Among many of the poets and literary writers widely read in Cuba and lesser known outside the island are: the poet Fayad Jamís; the towering literary critic and essayist Anton Arrufat, who can still be seen most elegantly dressed in restaurants and hangouts of Havana; late playwright and exile Virgilio Piñera, whose correspondence with Arrufat has recently been published in the country where Piñera (to a greater extent than Arrufat) was once subject to censorship and persecution despite his support for the revolution. Poets Soleida Ríos and the late Ángel Escobar capture the hallucinatory experience of Santiago de Cuba where Afro-Cuban culture is centered. Among experimentalists are Juan Carlos Flores. The present day sage, poet Roberto Manzano supports younger poets such as Arístide Vega, Idiel García, Kiuder Yero. (More experimental voices included the Biblically-minded Aparicio Fernandez Robaina and veteran military pilot Erick Tamayo, I am honored to be their translator.)

Next door to the Dulce María Loynaz cultural center was a museum with the largest exhibit being of Dulce María Loynaz’ hand fans, all of them in varying ways ornate, of shapes and colors that resembled the bio-complex of diverse dangerous fish at the bottom of an Amazon river. In a room adorned in fans resembling a collection of winged insects of tropical woods, Zenófono forgot the festival schedule and wandered, enthralled, doctor’s coat in his arm: as if he himself had become a drunken night-moth, in the toyshop of his heroine-poet Dulce María. The museum showcasing mostly her collection of fans resembled an immense doll’s house, and was staffed and monitored by older, uniformed and dutiful Cuban women who had always wanted permanent employment in a giantess doll’s house. Solemn watch-women, they guarded the precious fans, and the strange, painted bourgeois porcelains made in Cuba with blue-eyed blond flute-boys and satyrs, trinkets once belonging to the hated “esclavocracia’’ or the former slave-owning bureaucracy before the abolition, which took place before José Martí’s poetic-patriotic armed revolution, which (in turn) preceded what is generally remembered as The Revolution of the mid-20th century. On the way out of this odd exhibition I asked my guide to tell me about the infamous Gray Period or the “Quinquenio Gris’’ in the island’s memory. My question dispelled the childlike drunken spell that had earlier fallen over Zenófono. He would tell me about the Gray Period of shame, but first I had to buy him a guayaba and papaya malt-shake to talk in this heat.

Gray Years and Penitentiaries

Unlike in Soviet Russia, the Cuban revolution in its earliest phase was not “iconoclastic’’ for it had not obsessed over destroying any relics of the bourgeoisie’s past, as the ornate houses of Vedado attest, well-maintained by the descendants of slaves and peasants who inhabit the expropriated houses. Originally, Castro had even stated that the revolution ‘’did not seek to make the rich man poor,’’ and to the contrary, the revolutionaries naively hoped that a nationalistic bourgeoisie with altruist and patriotic consciousness would even support the revolution against international adversaries. The recent warm welcome given to President Trump by Cuban lobbyists in Miami showed how wrong the revolutionaries were in some of their theoretical expectations.

Only during the late 1960s and early 1970s, did Cuba enter the period that is today fervently discussed within Cuba: the “Quinquenio Gris’’ or the “Gray Five-years’ (or “the Gray Lustrum’’) a time of official paranoia and Stalinization. This occurred after the death of Ernesto Guevara, and the first major attacks and bombings upon Cuban soil by US forces. Like any small nation, the island responded to terrorism, blockade and isolation by becoming much more reactionary, compromising many of the liberties that had been won by struggle.

During that period, those Cubans who reminded officials of echoes of the North American countercultural youth movements of the era, were rounded up and sent to an asylum-like penitentiary. These included the popular singer Pablo Milanés, who supported the revolution, but who today (still a resident and broadcasting artist in Cuba) has said ‘’the revolution stood still’’ which is taken as injurious or subversive by officials who typically claim to be upholding a state of ‘permanent revolution’’ even as Raúl Castro begun introducing practices anathema to socialism, such as taxation, for citizens.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kU9JE_k-XcQ

Singer-songwriter and revolutionary Silvio Rodriguez, who some call the greatest living Cuban poet, was also subject to the detentions and persecutions of the era. His involvement in the revolutionary organization and ideology not only got him out of ‘’Gray’’ trouble: it also enabled him to come to the aid of other more vulnerable Cuban artists who had fewer radical credentials, like Pablo Milanés, whose Oscar-Wildean antics (considered dandyish for the time) and dress reminiscent of North American hippiedom were not endearing to the bearded and tough Platonic guardians of the most recent revolution, just returned from aiding anti-colonial wars in Africa. Milanés started the “Nueva Trova’’ movement, one of the new troubadours of his generation, with songs that were often more personal such as ‘’Mis 22 años’’ My 22 Years, rather than containing only purely revolutionary content. Milanés also made songs of protest against the horrors of the American invasion of Vietnam. Rodriguez continues to believe in the values of the Cuban revolution, and is one of most beloved poets and performing artists among the Cuban people and in Latin America.

The Manichean “gray” era ended (perhaps, as Milanés sardonically said, so did the revolution’s dynamo). Music once forbidden — sounds smacking of hippiedom, the Beatles, psychedelic rock— as well as music that was later on prohibited, such as the music of Celia Cruz (who had moved to Miami and often made public statements denouncing revolution and calling Castro “the devil”) are once again permitted. Exiles like Virgilio Piñera, formerly censored, are widely published and very popular among the young, including the publishers and editors of La Luz, publisher dedicated mostly to young writers, based in the province of Holguín, the region where many Cuban literary giants, as well as young contemporary writers were born. By day Holguin’s capital is wind-battered and dusty. Horse-pulled, wooden creaking carriages are a common mode of transport in the unpaved streets of the city center. At night the thrives with cultural events, poetry readings and concerts, and many cafés frequented by a large young population.

In the Vedado area Havana, there is a popular bar-disco called The Yellow Submarine, a haunt where Cuban science-fiction writers often meet (Zenófono could not explain to me as to why they chose The Yellow Submarine, perhaps a code shared by the initiates)

Cuban science fiction writers, like Yoss José Miguel Sanchez and Malena Salazár Macía can at times be found there as covers of mostly North American rock bands play.

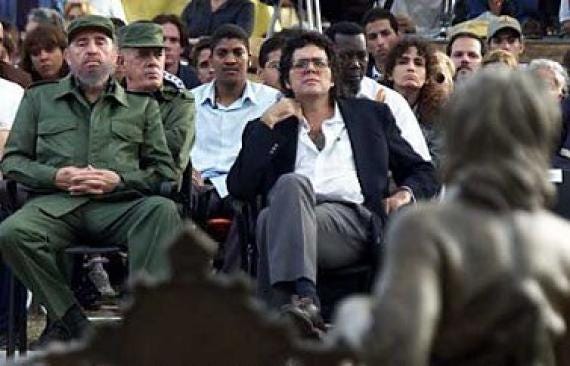

The club is of course not far off from the John Lennon Park, where there sits a gilded-painted statue of John Lennon upon a park bench. (I marveled much more at the statue dedicated to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg) The Statue was unveiled by Silvio Rodriguez and Fidel Castro Ruz, a ritual of trying to do away with the legacy of the “Quinquienio Gris’’ In one picture, Pablo Milanés sits looking on bitterly at the commemoration, in the chair next to Fidel Castro, the history between them not entirely appeased by ceremony

The beauty of the old houses in Vedado — neo-baroque fantasies of the early 20th century’s bourgeoisie, all expropriated and given to large proletarian families — are by no means in decay, despite not having protection from Unesco ( as does the more deteriorated yet still beautiful Otra Banda neighborhood in Curaçao)

No less remarkable is the visible presence of the once-controlled and even forbidden Santería or Yoruba religion. It was not uncommon to see, on a street corner, a child dressed in flowing white silk and a silken turban, pinned with flowers and gowned with many color-coded beads of the Yoruba religion to celebrate the Saint’s day, the day of a particular deity in the Afro-Caribbean religion is celebrated by those who believe that deity is their protector, not unlike the baptisms, confirmations and bris-mila of monotheistic faiths. Santería is no longer clandestine as it was for the previous four centuries — a prohibition that began in the 17th century and surprisingly continued, under entirely different justifications (a Marxist war on ‘superstition’) after revolution. References to the religion are everywhere in the popular music from Santiago. Yoruba was of immense interest to novelist Alejo Carpentier, a revolutionary who studied the Afro-Cuban musical culture and religion as well as the Haitian revolution. A poet of recent times who was more directly influenced by the religion of African slave ancestors was Ángel Escobar, whose origins at the rural, economic and provincial margins of Cuban society, and whose seclusion while struggling with mental health ended in suicide, putting him in a very different position than that of the globetrotting, vivacious Franco-Cuban Carpentier.

The Casa de Las Américas (House of the Americas)situated in a tower by the Malecón seaside is a signature institution of the Cuban revolution, once directed by Roberto Fernandez Retamar, the author of “Todo Caliban’’ ‘’All Caliban’’, an intellectual comrade/paramour of Edward Said of the Caribbean.

Zenófono kept assuring me on Facebook throughout the months of September, October and November that Clearance, which sounded like deliverance, was imminent and the official letter of Invitation on its merry way. He apologized for the slowness and strict controls on Cuban internet, explaining during his hospital breaks he sat outside, by a fountain amid many crouched bodies who were checking the Facebook and email electro-scrolls on their hand-phones, marveling at the revolutionary Neo Telegram technology that was new to the island, previously prohibited or controlled by the Customs, Telecommunication and Public Health. His use of internet relied heavily on coupons that depleted quickly and were rationed for hygienic daily usage, just as the guaranteed supplements of coffee, salt, sugar, rice and tea were rationed to each and every citizen, securing the revolution’s guarantee that no one need die of hunger or treatable illness. I trembled with anticipation to once more see Cuba. Limbo was shaken by news of a famous death.

The death of Fidel was a shock to Cuba and to much of the planet. Many Cubans no longer expected Fidel to die, assuming he would live forever, after the famed 600 assassination attempts by the CIA and by Cuban-exile hatchet-men like Fernando Posada Carriles. Hitmen like Carriles, author of terrorist bombings that killed civilian airline passengers and tourists, attempted every shenanigan of comical death, with all the creativity of a School of the Americas’ Masters of Fine Arts in Creative Torturing: from the explosive-rigged Montecristo cigar, to the exploding mollusk assailing the presidential yacht, to poisoned dinners that led Fidel Castro to a habit of skipping meals and training his dance-floor-linoleum-lined gut, while he travelled on Cubana Air 1 to meet other Third World leaders. “The C.I.A. taught us everything — everything,” Carriles told The NY Times in 1998. “They taught us explosives, how to kill, bomb trained us in acts of sabotage.”

To cite from the Uruguayan author Eduardo Galeano’s ‘’Mirrors’’ (in Danica Jorden’s English translation https://www.opendemocracy.net/democraciaabierta/eduardo-galeano/fidel):

“His enemies call him a king without a crown who confused unity with unanimity.

And they were right.

His enemies say that if Napoleon had published a paper like “Granma”, nobody in France would have found out about his defeat at Waterloo.

And they were right.

His enemies say he ruled by speaking a lot and listening very little, because he was more used to echoes than voices.

And they were right.

But what his enemies don’t say is that he wasn’t posing for posterity when he met the invasion’s bullets chest first, (…) that he survived six hundred and thirty-seven assassination attempts, that his contagious energy was the deciding factor in turning a colony into a country

And they don’t say that this revolution, which grew up under sanctions, became what it could be and not what it wanted to be. And they don’t say that the wall between wishes and reality became bigger and wider mainly because of the imperial blockade that choked the development of a Cuban-style democracy, forcing society to militarize and bureaucratize...”

Perhaps the survival of such creative assassins as those deployed upon him from Miami and Washington had finally convinced him, that belief in the supernatural was to be accepted and tolerated among his people, many of whom are religious practitioners. Marx’s dictum ‘’Man is not creating any problems we are incapable of solving’’ proved too simplistic, a naiveté about science better confined to the 19th century. Hopefully, the values of the revolution can continue to find expression in new and undogmatic ways, without censorship, by the believers in the African and Middle Eastern religions, and most importantly by the poets and musicians animated by the intimate motor of future struggle.

This was the prelude to the report on the actual Encounter of Young Latin American and Caribbean Writers in Havana, 2017. More in following months.

Arturo Desimone, Arubian-Argentinian writer and visual artist, was born in 1984 on the island Aruba which he inhabited until the age of 22, when he emigrated to the Netherlands. He relocated to Argentina while working on a long fiction project about childhoods, diasporas, islands and religion. Desimone’s articles, poetry and fiction pieces have previously appeared in CounterPunch, Círculo de Poesía (Spanish) Acentos Review, New Orleans Review, in the Latin American views section of OpenDemocracy and he writes a blog about Latin American poetry for the Drunken Boat poetry review.

Notes on a Journey to the Ever-Dying Lands was originally published in Anomaly on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.