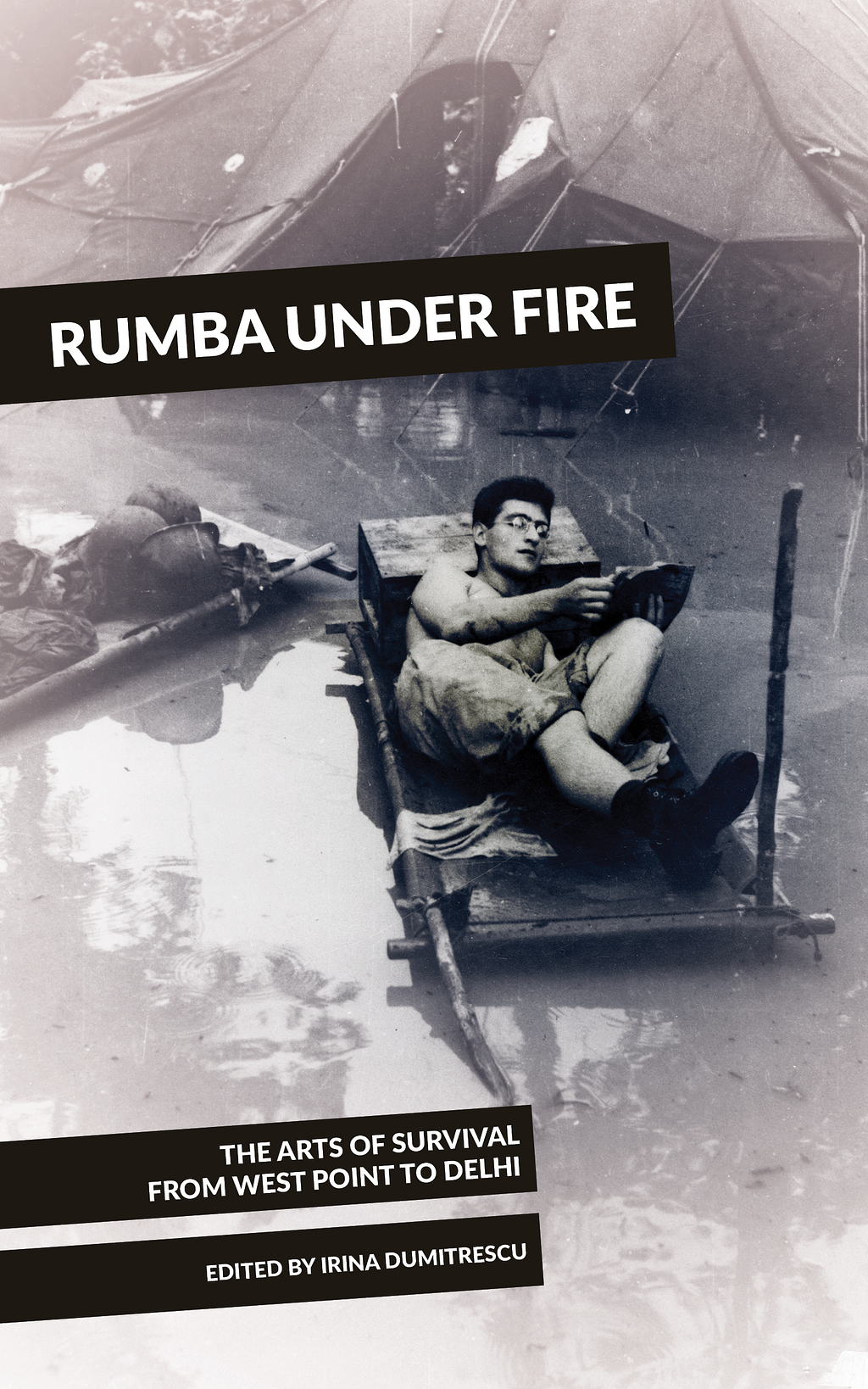

Many of us have heard, or read, that there is currently a crisis in the humanities. We may think of falling enrollment when we hear or read these words, or of a lack of funding, but as editor Irina Dumitrescu points out in her introduction to Rumba Under Fire: The Arts of Survival from West Point to Delhi, a multi-genre collection of essays, academic scholarship, interview, and poetry from Punctum Books, the humanities extend beyond the university. In addition, as Dumitrescu cogently points out, “while decreasing liberal arts majors and the adjunctification of the university are deeply threatening to humanistic study, so are war, incarceration, censorship, exile, and oppression. Intellectuals have been at the mercy of direct persecution or general political turmoil at least since Socrates was executed in 399 BC for his impiety, considered a corruption of the young men of Athens.”

Indeed, the specters of incarceration and political turmoil, war and censorship, take center place amidst the varied entries in Rumba Under Fire. Personal hardship meets and mingles with unfortunate and oppressive, sometimes deadly political realities, yet many of the individuals discussed in these pages find the ability to continue to exist by engaging with learning, art, music, food, literature, and history despite their dreadful surroundings.

Indeed, the specters of incarceration and political turmoil, war and censorship, take center place amidst the varied entries in Rumba Under Fire. Personal hardship meets and mingles with unfortunate and oppressive, sometimes deadly political realities, yet many of the individuals discussed in these pages find the ability to continue to exist by engaging with learning, art, music, food, literature, and history despite their dreadful surroundings. Two of the essays (“Poems in Prison: The Survival Strategies of Romanian Political Prisoners,” one of Dumitrescu’s contributions to the collection, and “Writing Resistance: Lena Constante’s The Silent Escape and the Journal as Genre in Romania’s (Post)Communist Literary Field” by Carla Baricz) both discuss the very real hardships for imprisoned intellectuals of Romania before the 1989 revolution, but also describe what they did to survive as thinking, feeling human beings. (It is worth noting, for example, that Lena Constante’s prison journal was not a physical object, as there were no pens or paper at her disposal. Rather, Constante’s journal was a document of memory, written down after her imprisonment came to an end, along with some of her creative work that she could still remember, such as plays she composed while imprisoned.)

Food, we are reminded, is often inextricably linked to culture, and it is worth remembering that the National Socialists were also attempting to eradicate a culture. This becomes especially apparent when we learn that many of the recipes contained in the book don’t work as recipes at all, thus suggesting that it was not the imagined end products of the recipes that sustained, but the act of their transmission from one woman to another.

Elsewhere in the collection, Cara De Silva, editor of In Memory’s Kitchen: A Legacy from the Women of Terezín, a collection of recipes written down from memory and passed between women imprisoned in the Nazi Theresienstadt/Terezín camp, and Dumitrescu discuss how dreaming about food, and the nourishment and community feeling that often intersects with cooking, gave some victims of unimaginable oppression and degradation a reason to keep existing. (Food, we are reminded, is often inextricably linked to culture, and it is worth remembering that the National Socialists were also attempting to eradicate a culture. This becomes especially apparent when we learn that many of the recipes contained in the book don’t work as recipes at all, thus suggesting that it was not the imagined end products of the recipes that sustained, but the act of their transmission from one woman to another.)

Throughout Rumba Under Fire, standard academic scholarship rubs shoulders with poetry, personal essay (such as Susannah Hollister’s account of teaching poetry at West Point, framed by how she and her husband tracked time during his year-long deployment in Afghanistan), or the personal essay bridged with history …

Music as a force that both sustains and offers commentary on lived experience also enters these pages, such as in Judith Verweijen’s essay, “Rumba under Fire: Music as Morale and Morality in Music at the Frontlines of the Congo.” However, the essays, poems, and scholarship in Rumba under Fire never run the risk of romanticizing hardship. Often, as readers, we witness the anti-romantic, even as we are sometimes presented with troubling questions. (If, for example, artists or writers are oppressed to the point that they cannot produce art or writing, how can art or writing be part of resistance?) We also learn, for example, some particulars of how legacies of Western colonialism have shaped and intersected with reactions to the humanities in some geographical regions, even after an end to colonial rule.

Prashant Keshavmurthy’s essay, “Profanations: The Public, the Political and the Humanities in India,” describes how conservative religious calls for censorship are centered in colonially-imposed monolithic identities. As Keshavmurthy writes: “we begin to glimpse the outlines of a dominant formation of mass religious identity in modern India: the fetishistic hyper-investment in traditional forms of faith in displaced response to political disenfranchisement.” In turn, Anand Vivek Taneja discusses in “Village Cosmopolitanisms: Or, I see Kabul from Lado Sarai” how examining alternative ways to view and process past history (in this case, between Hindus and Muslims) can open doors to different understandings of the future.

The book makes a cohesive argument not just about how engagement with the humanities can help temper or explain various political or humanitarian crisis, but that there will always be multiple, equally vital ways — from poetry to scholarship, and more — to process ideas in and of themselves, and that these multiple approaches can be tools for survival in harsh times.

Throughout Rumba Under Fire, standard academic scholarship rubs shoulders with poetry, personal essay (such as Susannah Hollister’s account of teaching poetry at West Point, framed by how she and her husband tracked time during his year-long deployment in Afghanistan), or the personal essay bridged with history (such as William Coker’s account of teaching western humanities in Turkey, which also delves into the origins and legacy of Turkish Republicanism, and, by its end, manages to question what it means for a text to count as ‘western’ at all). In a way, though, it feels foolish to attempt to divide the entries in Rumba Under Fire by genre at all, though it may be helpful as a basic description of the text in question to highlight its multi-genre nature.

And nature is the right word, because Rumba Under Fire, as a collection, is bolstered not only by the varied, unique efforts of its contributors (many of whom I have not mentioned here, simply for matters related to space), but because, in its multi-genre essence, where each genre is given equal privilege, and genres are not sequestered into separate sections, the book makes a cohesive argument not just about how engagement with the humanities can help temper or explain various political or humanitarian crisis, but that there will always be multiple, equally vital ways — from poetry to scholarship, and more — to process ideas in and of themselves, and that these multiple approaches can be tools for survival in harsh times.

RUMBA UNDER FIRE: THE ARTS OF SURVIVAL FROM WEST POINT TO DELHI, edited by Irina Dumitrescu was originally published in DrunkenBoat on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.